Understanding Ukraine as it exists today is only possible if we look carefully at the past. The transition from imperial domination to European integration is one of the core themes in recent European history. In that sense, Ukraine’s history is a microcosm of a much wider story. As IWM Permanent Fellow Timothy Snyder explained in his keynote speech “Ukrainian History as World History 1917-2017,” part of the conference Revolutionary Ukraine: A Reflection on 1917 and Its Aftermath, these transformations were already at play in 1917. The concept of the nation-state was the rallying flag of anti-imperialist movements raging in the Balkans against the Ottoman Empire, for example. The Ukrainian experience, because of its position on imperial peripheries, therefore, resonates with European and global themes.

Any account of the history of Ukraine has to include two of the most significant events of the 20th century: the Holocaust and the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Historian Serhii Plokhii, author of Chernobyl: History of a Tragedy, and international lawyer Philippe Sands, author of East West Street: On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes against Humanity”, explored possible ways to understand the destruction of the 20th century in their 2019 conversation “Humanity and Catastrophe,” part of the conference Between Kyiv and Vienna.

How might the legacies of the past be legible in contemporary Ukraine? Internal divisions characterize virtually every post-communist country, but in the case of Ukraine they have played a decisive role in the country’s (under)development, argued Ukrainian public intellectual Mykola Riabchuk in his 2002 essay “Ukraine: One State, Two Countries?” (in Tr@nsit online, Nr. 23). He posited that the social and political phenomenon of “ambivalence” was a key characteristic of post-Soviet Ukraine, one which emerged from Ukraine´s regional, cultural and linguistic differences as well as from Soviet totalitarianism. Even if the elites of the immediate post-independence period were able to use these divisions to their advantage, Riabchuk contended that a nascent civil society in Ukraine had the potential to transcend its post-Soviet ambivalence.

Riabchuk’s influential if controversial notion of “two Ukraines,” which underlies his exploration of ambivalence, has engendered robust debate, including two valuable responses to this essay in particular. In “The Myth of Two Ukraines,” political scientist and former UiED Research Director Tatiana Zhurzhenko challenged the idea that there is a clear divide between a supposed ‘europeanized’ West and a more ‘russified’ East. Historian Roman Szporluk argued in his commentary “Why Ukrainians are Ukrainians” that Riabchuk’s concept of ambivalence needs to be situated in more historical terms: unlike other post-Soviet countries, Ukraine as a political entity was only firmly established in 1991, and in the early 2000s its civil society and statehood remained immature.

One strategy to transcend internal divisions has been suggested by historian Yaroslav Hrytsak. His 2010 essay “Ukraine 1989: The Blessing of Ignorance” sketched out a strategic compromise around identity issues, such as the status of the Russian language, foreign policy orientation, and historical memory.

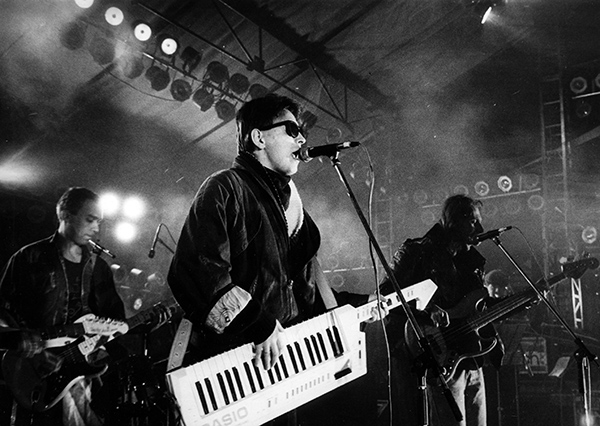

The cultural landscape has played a key role in shaping independent Ukraine. Yuri Andrukhovych, one of the country’s foremost contemporary writers, explored the distinctive spirit that animated Ukrainian culture on the cusp of independence in his article “The Festival Age: Origins of a Phenomenon” in IWMpost #126. He recounted several significant cultural events that both reflected and shaped Ukrainian society and art at that time and tied into the zeitgeist of Eastern Europe more broadly.

Ukraine’s three decades of independence have been marked by significant political upheaval. The Maidan movement, also referred to as the “Revolution of Dignity,” took place between November 2013 and February 2014 and was a turning point for Ukrainian society. The Maidan prompted the IWM to deepen its engagement with Ukraine, leading to the establishment of the Ukraine in European Dialogue program, as well as several efforts to make sense of the Maidan in the near aftermath.

Tatiana Zhurzhenko and Timothy Snyder gathered impressions from those who witnessed events first-hand. Published by IWM’s partner magazine Eurozine, these diaries and memoirs of the Maidan offer gripping personal accounts as well as insightful observations into the nature of the protests and the state’s response.

Ukrainian intellectuals were also invited to write about their revolutionary experience in other venues. For example, Kharkiv-based translator and literary editor Zaven Babloyan, who spent his childhood in Luhansk, was a fellow at the IWM in 2014; his reflections have been presented in a thoughtful interview with Tatiana Zhurzhenko for Tr@nsit online: “Kharkiv Talks in a Viennese Kitchen – On Revolution, War and Literature in Ukraine.”

Other reflections, including those from IWM fellow and publisher Kateryna Mishchenko, publisher Oksana Forostyna and philosopher Mykhailo Minakov, were published in Issue 45 of the journal Transit, Maidan: Die unerwartete Revolution (Maidan: The Unexpected Revolution).

Before and especially after the Maidan, the IWM has hosted junior fellows from Ukraine, a new generation of scholars whose lives have been lived mostly or wholly in independent Ukraine. For example, Olha Martynyuk reflected on Kyiv’s architectural landscape, and on how the division between the city’s uptown and downtown reflect the livelihoods of its inhabitants in her contribution to the 2012 Junior Fellows’ Conference, “Sacred Hills and Commercial Downtown: Ethnic Meanings of Urban Spaces in Late Imperial Kiev.”

Mykola Balaban explored the logic of violence as illustrated by a microhistory of the first two weeks of the Nazi-Soviet war in Lviv in his 2019 Junior Fellows’ Conference paper, “Two Weeks of Interconnected Violence in Lviv Prison Massacres, Anti-Jewish Pogroms and Murder of Polish Professors on June 22th – July 4th, 1941.”

Iryna Sklokina’s project at the IWM looked at commemoration practices of the Second World War and the reappropriation of public monuments in post-Soviet countries as leisure spaces. In her essay for IWMpost #127, “Holy Places and Leisure Spaces,” she looked at international tourism as a key determinant in understanding the performative aspects of commemoration culture.