How an ambitious and a politically driven imagination of a post-imperial culture was overtaken by the project of building a culture for the nation-state in postcolonial India.

When seen from Europe or the United States, the onset of the Cold War appears to define global history after 1945. But viewed from the ex-colonies, decolonization and the struggle for a world after empire emerge as the central theme of postwar history, one that led to the rise of the idea of the Third World.

Historiography has made the Third World a geopolitical term or a geographical descriptor. However, for Frantz Fanon, the idea of the Third World was not merely about political sovereignty but something much more ambitious: the creation of a different world, a world after empire. It was not about development or “catching up” with Europe. The challenge was to create a new universality, a new humanism, a new life.

Underlying this vision of a new world was an attention to culture. Anticolonial intellectuals understood that colonialism was not only about military conquest and economic exploitation but also about cultural domination. Fanon argued that a new national culture could be the basis of a postcolonial future. His vision of national culture was not about recovery and revival of the past, but one created by the anticolonial struggle. Politics was to produce national culture. He insisted that it had to be something composed and cultivated by political struggle.

This dynamic and a political struggle-based national culture, Fanon believed, could be the basis for international solidarity. According to him, “National consciousness, which is not nationalism, is alone capable of giving us an international dimension.” There are two points to note in this statement that are of contemporary relevance. First, it was a vision of globalism based on political struggle and solidarity, not one of market-based globalization. Second, the vision of an anticolonial national culture is different from the ascent of nationalist culture we are witnessing today.

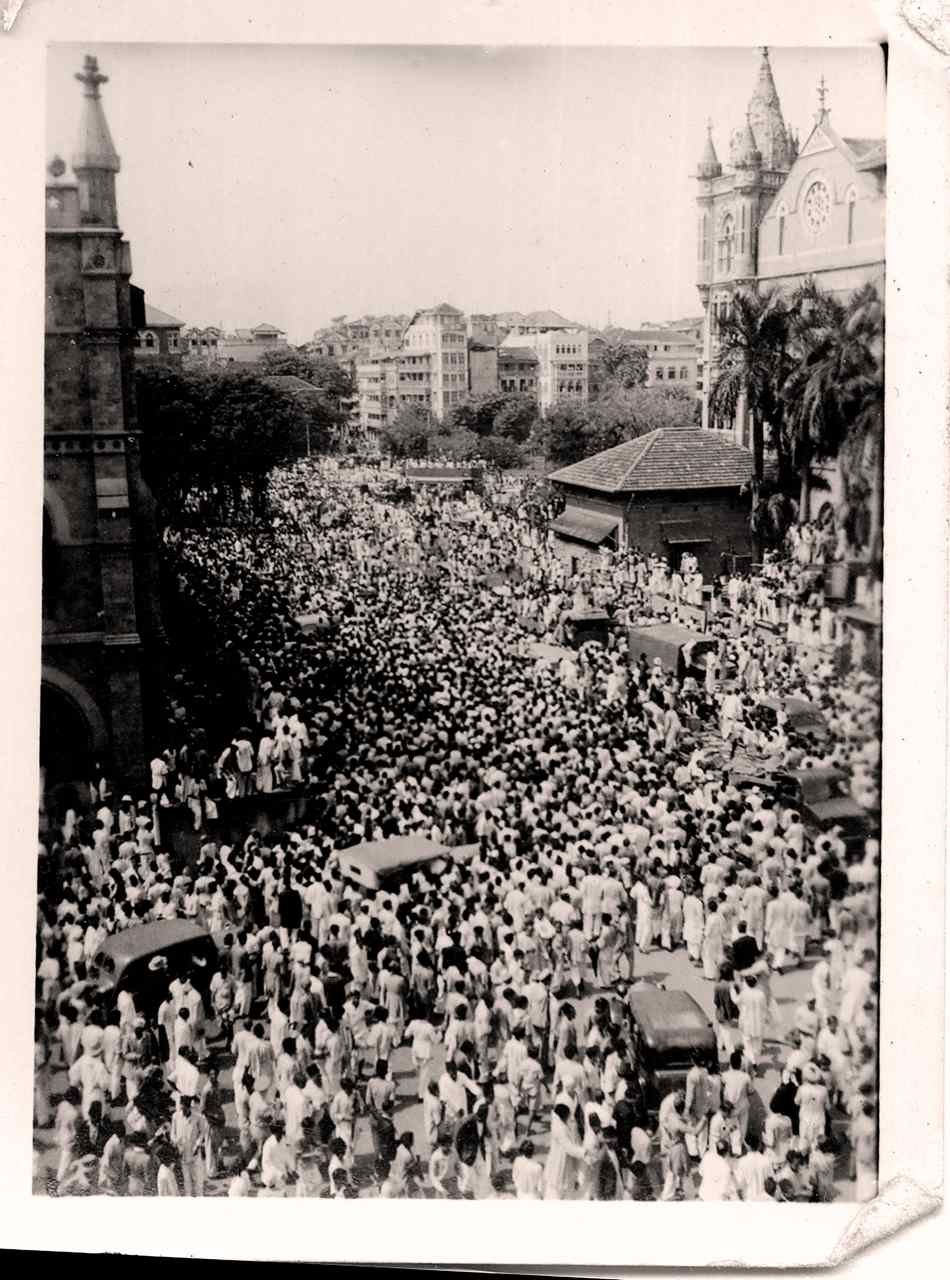

Indian anticolonial leaders also thought that the nation could be the basis for a new social and political order, and for an internationalism different from the inequality of imperial globalism. They valued newness and youth. Mahatma Gandhi, with all his reverence for what he called India’s civilization, named his journal Young India. His press was called Navjivan Press—New Life Press. B. R. Ambedkar called his form of Buddhism Navayana—the new vehicle. Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous book was titled The Discovery of India. For most Indian anticolonial activists, the nation was not something narrow but part of a cosmopolitan, modern, and international system. Opening the Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi in 1947, Nehru declared: “We stand at the end of an era and the threshold of a new period of history.” He planned no revolutionary overthrow of the colonial order, but the soaring rhetoric of the “new period of history” expressed yearnings for radically new beginnings.

On the ground, there were attempts to build a new, radical national culture based on anti-imperialism and social equality. An expression of this was the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was formed in Mumbai in 1943. A communist-led organization, its performances were often propagandist and contained pro-Soviet themes. But it was not just a communist front. IPTA brought together leading cultural practitioners in art, music, dance, poetry, and theater, many of whom went on to win national and international recognition. Its work anticipated the Fanonian spirit of building a national culture as part of a political struggle against imperialism and capitalism. It offered the first serious critique by Indian artists of colonial capitalism and envisioned a radical theater of the “people.”

IPTA had two basic goals. First, to develop forms outside the naturalistic and commercial alternatives to advance the struggle against imperialism, capitalism, and fascism. Second, to draw on India’s rich folk forms to create a popular alternative to the bourgeois, urban colonial theater. Over the decade or so after 1943, IPTA produced and performed hundreds of social-realist plays. These toured extensively, depicting struggles against feudal, capitalist, and imperialist domination.

The 1940s and 1950s were IPTA’s heyday. Its Central Cultural Troupe, with prominent artists from Bengal and Mumbai, toured the country to stage radical plays, and music and dance performances. While these were high-profile, the real work was carried out by local troupes in regional languages. Mumbai, for example, was an important location for IPTA’s activities. Not only was the city a hub of writers and artists, its cotton mill districts also became the scene for very lively and important cultural work. The performers were often drawn from among workers, who brought and reinterpreted the Marathi tamasha traditions on the stage. Two artists, Anna Bhau Sathe (1920–1960), a Dalit, and Amar Shaikh (1916–1969), a mill worker , formed the Lal Bawta Kalapathak (Red Flag Cultural Squad) that served as IPTA’s wing in Mumbai. Grounded in the culture and politics of the working classes, they became iconic figures for their plays and poetry that repurposed Marathi folk forms to advance radical ideas of justice and freedom.

By the late 1950s, however, IPTA had lost ground, for many reasons. First, the communists’ combative stance toward Nehru’s government was met with strong repression. Second, even IPTA artists had trouble accepting the communist line that India’s independence in 1947 was a false one. Third, many artists considered the performances as political propaganda masquerading as art. In any case, the central goal of producing “people’s art” remained unfulfilled. With exceptions, what IPTA produced was not “people’s art.” Instead, urban intellectuals brought radical art to the people, interpreting folk art for the folk. The worlds of radical middle-class intellectuals and Dalit and subalterns did not often intersect. As working-class and peasant struggles under communist leadership floundered by the late 1950s, the vision of forging a political struggle-based culture was not realized.

Another important reason for its failure was that the Nehruvian state entered the cultural arena to build and promote national culture. Nehru was committed to the idea and considered it vital for national unity. Given the background of violence accompanying the partition of British India, the country’s cultural diversity, and the Kashmir crisis, Nehru and other leaders thought of India in terms reminiscent of the “state of nature” in Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. The turmoil of imperial retreat created a situation in which only the state could manage the anarchy and create national unity. Thus, building a national culture was vital if India was to achieve national unity and develop as a modern nation. With this in view, Nehru established institutions that became powerful cultural bodies offering patronage to artists and writers in different languages, and drawing them into the state project of building a national culture.

But the state project was a profoundly culturalist one. When Fanon spoke of national culture, he intended a politically engaged and dynamic process. National culture was to be forged in engagement with the daily life and struggle of the people—it was precisely this aspect of struggle that could make the national the basis of international solidarity. This was also IPTA’s vision. Its theatrical activity was aimed at mobilizing the people against capitalism and imperialism. Didactic and propagandist though it may have been, it advanced a dynamic view of culture, forged in struggles against capitalism and imperialism. It envisioned the battle for Indian independence as part of a global movement against capitalism and imperialism. But its efforts were overshadowed by the Nehruvian state’s project to forge a national culture to advance national identity and unity. With independence from colonialism achieved through a “passive revolution”—that is, a political revolution without a social one—the state attempted top-down modernization. This was true as much for culture as it was for the economy.

Once the state captured the idea of national culture as a culturalist project, unrelated to political struggle, culture after empire became susceptible to nationalism. The state provided an important ground for the debate and discussion on what constituted national culture, what was an Indian aesthetic, or how modern idioms could be developed for traditional cultural practices. A debate disconnected from active democratic struggles of caste, class, and gender justice left itself open to interventions from other kinds of proponents of national culture. It was only a matter of time before Hindu nationalists would enter the arena to rail against the Nehruvian pluralist cultural project and press the claims of a majoritarian Hindu nationalism.

Gyan Prakash is the Dayton-Stockton Professor of History at Princeton University. He was a guest of the IWM in 2023.