Can the question of Europe’s identity still be asked, or has it already shattered under the weight of its contradictions? This essay examines Jan Patočka’s reflections about European and Czech identity to expose the limits of pursuing a definition of Europe. Today’s challenge is to acknowledge Europe’s problematic and multifaceted reality through intercultural dialogue and solidarity.

Grappling with the concept of “Europe” is a sensitive task. It means engaging with a fractured, volatile field of meanings perpetually slipping beyond any stable or coherent form. But Europe is also an idea whose very understanding is entangled with the burden of past and present violence that the term evokes.

The root of Europe’s complexity resides in an epistemological and ethical/emotional struggle. Epistemologically, the quest to define Europe appears incompatible with a multifaceted reality. Ethically and politically, it exposes the problematic issue of establishing boundaries and thus enacting a principle of exclusion. Therefore, the question of defining Europe today is misdirected, rooted in an ill-conceived idea.

From the sixteenth century, the topos of a strong and coherent European identity has been predicated on the selective appropriation of perceived virtues of humanity. Binary narratives—civilized vs. primitive, rational vs. irrational, modern vs. traditional—have shaped the core of the European paradigm and its ontological and political power. These have functioned as tools for subordination, facilitating European colonialism, imperialism, and the assertion of cultural, moral, and political superiority over external others and marginalized internal communities. However, defining Europe by what it is not—through external contrasts with other cultures and internal exclusions—ultimately destabilizes any coherent sense of European identity.

The danger of defining an identity through binary logic relies on the false assumption of a static and coherent essence, which naturally leads to exclusion and violence. Moving beyond this limited view reveals that individual and cultural identities are fluid and interconnected structures, full of contradictions, and characterized by a fundamental noncoherence.

From Impasse to Openness

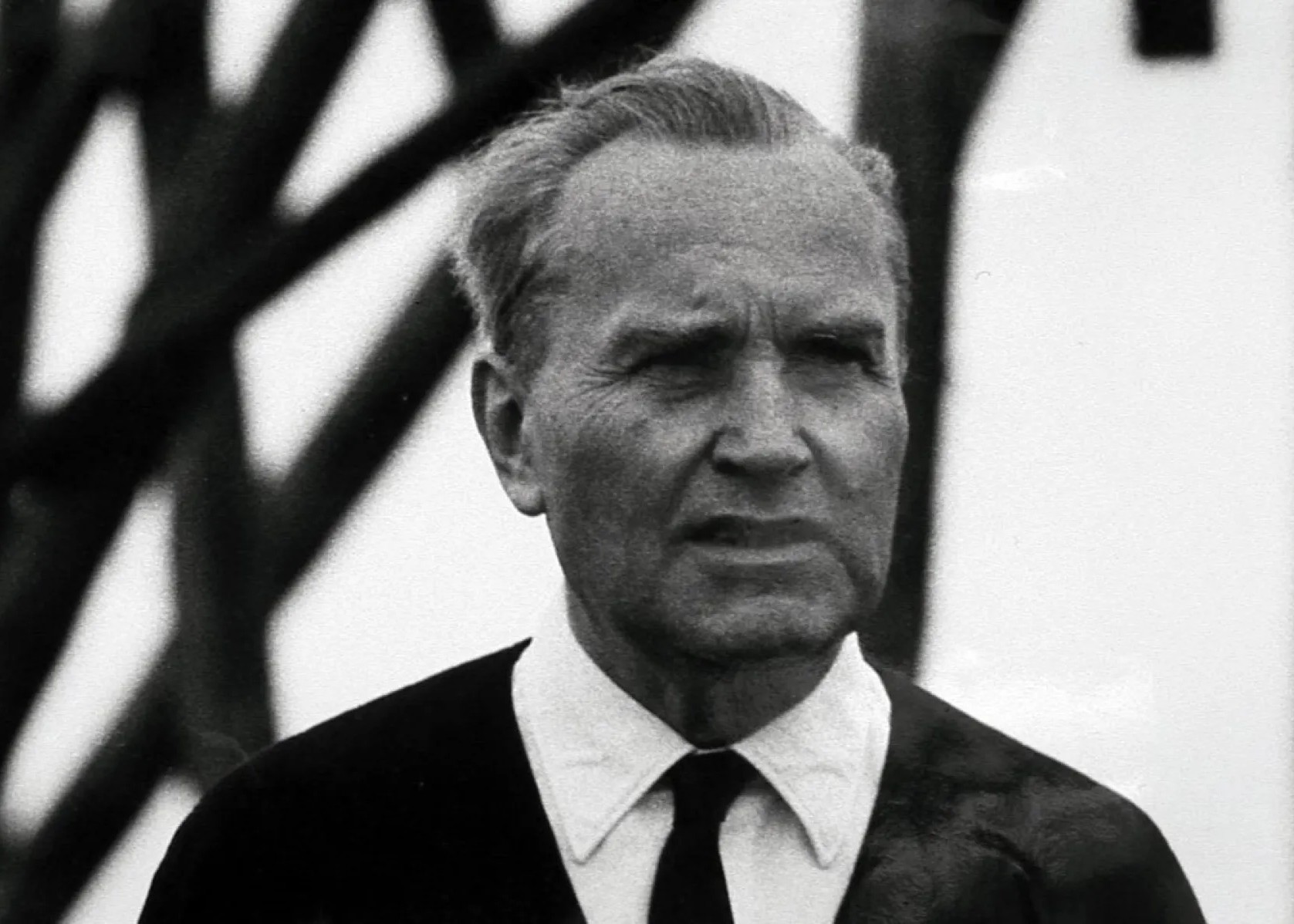

An endeavor to problematize Europe, confronting its inherent contradictions and the ambiguous legacy of its heritage, is evident in the work of Jan Patočka. His meditations are marked by a unique detachment, shaped by external and internal marginalization in a region often seen as being on the periphery of Europe. Developing his reflections as a “heretical” philosopher and a dissident European against Soviet domination, Patočka tried to distance himself from a teleological understanding of European culture, particularly that articulated by Edmund Husserl, due to its Eurocentric undertone. Neither the supposed superiority of scientific rationality nor the imposed universalizing hegemony of European culture offers a solution to the crisis of meaning caused by technicization, as Husserl thought. Rather, these very claims constitute the root of the problem, the European spirit’s curse upon itself and the world.

Throughout the 1960s, Patočka explored the deadlock of European identity in short philosophical fragments, which informed his broader philosophical theorization of the concept of Post-Europe. The seven fragments gathered under the title Was Europa ist… critique the limited scope of the European intellectual tradition, which confines its questioning of European rationality to its own insular circles, silencing the voices of other cultures. This narrow framework, Patočka argues, sustains Europe’s false sense of superiority. To truly detach ourselves from a Eurocentric perspective and to assess whether the concept of Europe still has meaning, we must disentangle its spirit from the systems of domination that have long defined it.

Patočka’s extensive reflections on the complexities of Europe are paralleled by his critical engagement with the question of Czech national identity, most notably explored in his work Was sind die Tschechen? This unveils another vital dimension of the European conundrum: the tension between European and national identity. What connects these two threads is their shared challenge to the nature of collective identity, rejecting essentialist frameworks. Both inquiries also address the central tension in the discourse of European identity between its inherent multiplicity, coupled with internal dynamics of marginalization and exclusion, and the closely linked issue of nationalism.

In this essay, Patočka undertakes a historical-phenomenological analysis of the Czech national political character. With his characteristic heretical gaze, he examines the role of Czech culture in the European landscape, sharply criticizing its self-inflicted “smallness” and its narrow, ethnolinguistically defined identity. Patočka delineates the risks inherent in this conception of national identity and advocates an alternative political interpretation of Czech, or more accurately, Bohemian identity. A few years later, this intellectual legacy informed the dissident discourse on critical patriotism and the renegotiation of national self-understanding.

While certain aspects of Patočka’s work, especially his notion of universalism, remain susceptible to Eurocentric critique as certain passages hint at a uniqueness of European culture, his inquiry into Europe’s identity raises important questions that resonate today. Among his most significant contributions is the concept of the “open soul”. Drawing from the writings of John Amos Comenius and Henri Bergson’s epistemology, the open soul is an alternative mode of individual and collective existence that appears throughout Patočka’s work on Europe. He uses this concept to theorize a subjectivity that perceives otherness not as a threatening externality to be overcome but rather as an invitation to confront one’s own finitude and free oneself from fixed, unilateral determinations. For the open soul, engaging with otherness becomes a polemical tension, a process of decentering oneself rather than aspiring to constitute a universal criterion. In this way, it embodies a fluid, multifaceted identity always in the act of problematizing.

Moving Beyond a Core Identity

Patočka’s idea of the open soul—which rejects mediation and domination, and relinquishes fixed determinations in its encounter with otherness—provides a model for individual and collective engagement in intercultural and intersectional dialogue. Furthermore, reflecting on national identity beyond the ethnolinguistic discourse and rethinking it on a civic-political basis could significantly help to create a practice of solidarity between individual and collective identities that resists capitalistic frameworks.

The act of problematizing Europe illuminates the political power embedded in the idea of a singular and definitive European identity, often wielded to assert European historical, cultural, and moral superiority. This monolithic narrative, particularly in its modern form that ties the label Europe with the European Union, erases the pluralities that exist within Europe and beyond. To truly understand Europe, we must acknowledge the reality of multiple Europes, recognizing the internal power dynamics and structural inequalities that sustain Eurocentrism.

Consequently, Europe’s challenge is in whether it can move past its universalizing tendencies and embrace a genuine pluralism, in which the voices of diverse internal and external cultures are truly heard. This transformation requires a political and ethical commitment to recognizing multiplicity not as something to be synthesized into a homogeneous unity but as something to be embraced in its asymmetry, allowing for the formation of self-contradictory, multilayered, and fluid identities.

Sofia Elena Merli is PhD candidate in philosophy at the Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa. She was a junior Jan Patočka fellow at the IWM in 2025.