While the term “Europe” was used in antiquity and the Middle Ages, it gained renewed prominence in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Global exploration and expanding communication networks prompted people to rethink the structure of the world. How did evolving ways of producing, sharing, and consuming information influence discourses on Europe, and why does this perspective remain relevant today?

The cultural, scientific, and political transformations of the early modern period, together with a markedly changing information landscape, significantly reshaped how individuals understood the world and their place within it. Between 1450 and 1600, there was a notable increase in attempts to define and describe “Europe,” particularly through maps, treaties, and historical compendia. Italy, with its thriving print culture, offers a vivid example of this trend. Looking back at the published materials, it is clear that for Italians Europe was not a fixed or clearly delineated concept, consisting of uniform building blocks, but a fluid construct that could accommodate a wide variety of cultures and peoples. This becomes especially evident in the evolving portrayals of Poland-Lithuania in Italy—an example that points to the importance of changing information practices in forming early modern views of Europe.

The Early Modern Information Revolution

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries witnessed a profound change in how information was produced, disseminated, and consumed. The widespread availability of cheap paper, the invention of print, rising literacy rates, and the establishment of professional postal networks led to an extraordinary growth in the volume of information circulating and in the speed of communication. People, goods, and ideas moved across ever greater distances, creating a growing sense of interconnectedness. Early modern societies were flooded with information, so much so that, much like in today’s hyperconnected reality, contemporaries often remarked on the difficulty of keeping up. They commented on the sheer volume of materials, sensing its potential and its disorienting effects alike. This phenomenon has been labelled “the early modern information revolution,” a term meant not to describe a sudden or linear process but as a metaphor reflecting the deep quantitative and qualitative changes in how information was generated, distributed, and processed.

Information flowed through vertical and horizontal channels—via diplomatic dispatches, private letters, books, and other printed materials such as newsletters and pamphlets. It passed from person to person in bustling taverns, harbors, and village squares, drawn by a growing thirst for news and intensified curiosity. The entire approach to information underwent a fundamental transformation: it was increasingly treated as a resource to be gathered, organized, and used. It became a tool of governance and trade as well as a commodity in its own right—one bought, sold, and manipulated, with the first news professions developing by the end of the sixteenth century. These developments created the conditions for wider intellectual exchange, including for reflections on Europe.

The Renaissance (Re)Discovery of Europe

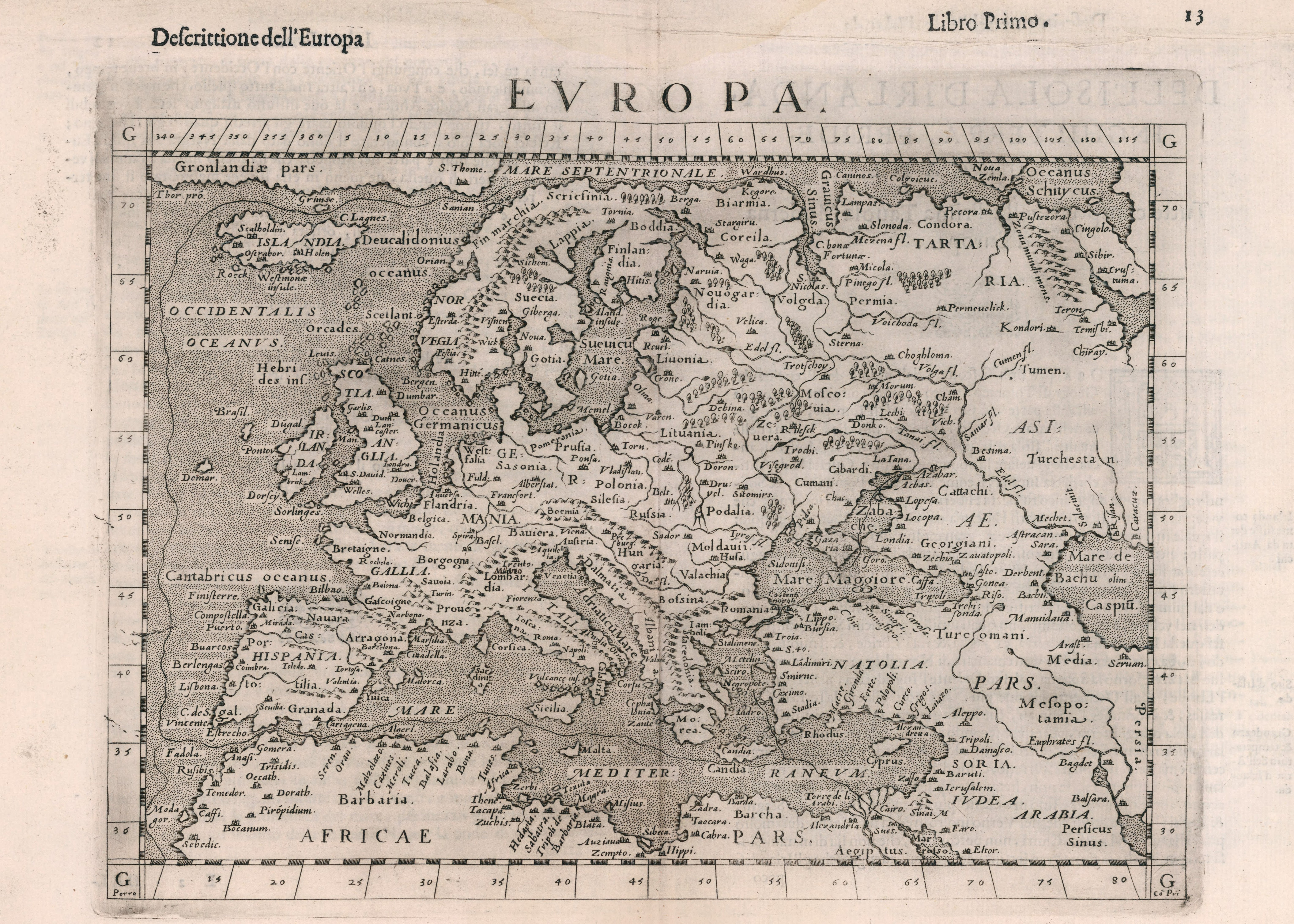

The advances and practices of the early modern information revolution greatly facilitated the spread of knowledge about Europe. In the early fifteenth century, Italian humanists turned their attention to classical legacies, recovering long-forgotten texts. A key moment came in 1407, when Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography, a second-century atlas of the Roman world paired with a treatise on mathematical mapping, was translated into Latin in Florence. Though known in the Arabic world, this was its first major reintroduction to a Latin-reading audience. Geography presented Europe as one of three known parts of the world, alongside Africa and Asia. While this reinforced Europe’s status as a distinct region, its boundaries and internal definition remained fluid. The text quickly gained popularity: by 1600, as well as nine Latin editions, eight Italian ones had been published in the Peninsula—a sign of growing efforts to reach broader audiences through vernacular versions. Many included updated and new maps incorporating information from recent voyages, including to the Americas. Geography became a key catalyst for early modern discussions about Europe and played a central role in the rise of printed cartography.

The revival of classical texts and access to more information also inspired new works. In 1458, Enea Silvio Piccolomini—later Pope Pius II—composed De Europa, a sweeping survey of the world, covering territories from the Iberian Peninsula to the Baltic, the Balkans to the British Isles, reaching deep into Central, Eastern, and Southern parts of the continent, including Hungary, Poland-Lithuania, Ruthenia, and the Ottoman lands. Piccolomini blended geographical description with political and historical commentary. He frequently and deliberately used the noun Europe and the adjective European: one of the earliest systematic efforts to embed these concepts in intellectual discourse. The interest in defining Europe continued into the sixteenth century as Italian humanists increasingly turned to contemporary sources to offer updated accounts of the known world. Publications like Paolo Giovio’s Historiarum sui temporis (1552) reflect a growing recognition of Europe’s diversity, grounded in new information circulating through merchants, travellers, diplomats, and students. Europe was no longer confined to the Latin West; it was seen as a dynamic, interconnected space stretching from the Atlantic to the Orthodox and Islamic worlds.

Disenchanting Poland-Lithuania

An example of how fluid perceptions of Europe’s regions were in early modern Italy can be found in the evolving depictions of Poland-Lithuania. In early Renaissance sources, this territory was often portrayed as a remote and vaguely defined place. Publications rooted in the Ptolemaic tradition placed the legendary Riphean and Hyperborean mountains—believed to be the source of all regional rivers and to be home to gryphons guarding fields of gold—within its borders. Such mythical motifs persisted in the early sixteenth century, appearing in maps of Europe and Poland-Lithuania produced by Francesco Berlinghieri (1482) and Marco Beneventano (1507). Beyond the realm of legend, Piccolomini’s De Europa offered a description that reinforced a sense of uncharted frontier. He depicted Poland as flat, forested, and sparsely populated, with Kraków as its sole centre of learning and culture. Lithuania fared even worse, reduced to a swampy expanse of woods. Piccolomini’s portrayal guided Italian perceptions of Poland-Lithuania well into the first half of the sixteenth century. As information flows expanded, the image of Poland-Lithuania evolved. By the late 1500s, works such as Giovanni Botero’s Relazioni universali (1591) offered a far more detailed and critical account. The mythical landscapes and laconic descriptions of earlier sources gave way to nuanced portrayals of the cities, political structures, and diverse cultures in the Commonwealth. Botero emphasized the rich intellectual traditions of Poland-Lithuania, described major urban centres like Kraków, Lviv, and Vilnius, and underlined the multiconfessional nature of the polity. His narrative drew heavily on reports by Italian diplomats who had visited the Commonwealth and on compendia composed by local authors.

Empirical and increasingly systematic information flows contributed to repositioning the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in Italian discourses, from a mythical periphery to a complex part of Europe’s political and cultural landscape. This historical example underscores the importance of cultivating diverse sources and acknowledging various knowledge centers. Rather than envisioning Europe as singular or fixed, we should recognize it as shaped through multiple voices and plural information flows.

Klaudia Kuchno is a historian and researcher at the European University Institute in Florence. In 2025, she was a guest at the IWM.