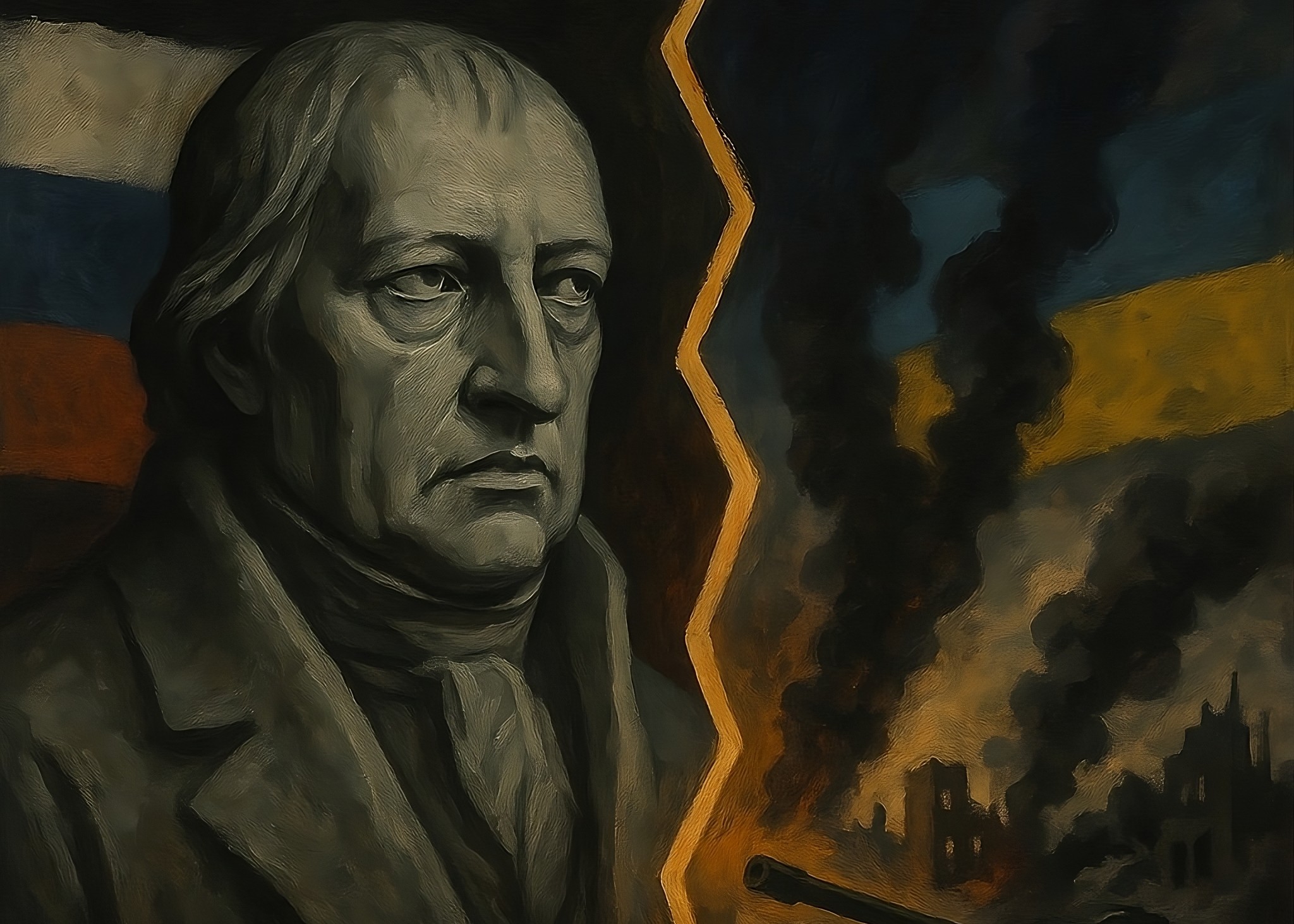

Among the four major figures of German classical philosophy, Hegel engaged most distinctly with international relations—a topic that philosophers typically either avoid or relegate to a passing footnote. Yet even in Hegel’s work, we do not find a fully developed theory of international relations that could be easily reproduced.

To construct a theory of international relations based on the writings of G.W.F. Hegel, it is helpful to rely on the well-established division in Hegelian scholarship: on one side, the traditional reading him as a realist; on the other, a more modern, Kantian interpretation. According to the realist reading, Hegel essentially echoes the views of thinkers like Niccolò Machiavelli or Thomas Hobbes. The Kantian reading, by contrast, presents him as building on legacy of Immanuel Kant, “who first channelled the doctrine of progress into international theory through his Perpetual Peace.”

At first glance, the traditional interpretation seems convincing. One of its most prominent proponents, E,H. Carr, even elevates Hegel to the rank of arch-realist:

The realist view that no ethical standards are applicable to relations between states... found its most finished and thorough-going expression [in Hegel]. For Hegel, states are complete and morally self-sufficient entities; and relations between them express only the concordance or conflict of independent wills not united by any mutual obligation.

Hegel, however, pushes realism even further. As Walter Jaeschke observes, “Outrageous is the fact that Hegel not only accepts war as the ‘ultima ratio’ in [an interstate] dispute, but that he also finds a ‘ratio’ in it.”

Hegel notes something obvious: war treats finite things, including state institutions and infrastructure, according to their very concept: as finite and therefore perishable. In this spirit, he ironically remarks that people go to church, where they are told that only God is eternal, and yet they return home surprised to find their houses destroyed by war—despite just having heard that only God, not their house, is eternal. More provocatively, Hegel suggests that war has a rejuvenating function for nations, reminding them of their own mortality.

Progressive readers of Hegel focus on very different passages. Like Karl Marx, they place their hopes in his dialectic. The dynamic, historically evolving vision of international relations they derive from Hegel stands in stark contrast to the static, ahistorical worldview of realism. As Andrew Vincent writes, “Hegel is describing the actual state of affairs of his time. He is not prescribing for all time that this should be so.”

Other scholars, such as Klaus Vieweg and Andrew Buchwalter, emphasize that not only individuals but also states strive for recognition from others. To be genuinely recognized as sovereign, states must cultivate their domestic institutions, respect constitutional order, and uphold the rule of law. This concept of interstate recognition is often used to challenge the notion that states merely collide like billiard balls or interact like Democritean atoms, as the mechanical model of realists’ balancing of power suggests.

Proponents of this reading also point to passages from Hegel’s Philosophy of History where he describes European nations as forming one family with a shared culture, which suggests the possibility of resolving tensions peacefully. Customs (Sitten) thus serve to moderate and civilize the state of nature. Others highlight the transnational character of Hegel’s concept of civil society, upon which states depend as part of a global capitalist system, which creates the need to manage shared economic conditions collectively. Finally, some emphasize the key methodological difference between realism and Hegel’s systematic philosophy. Whereas for realists anarchy “marks the starting point of theorizing about international life,” Hegel insists that the complete picture of the whole must emerge only at the conclusion of philosophical exposition. This is consistent with his critique of Baruch Spinoza’s geometric method, which begins prematurely with definitions of God (the whole).

The realist and Kantian-progressive interpretations of Hegel thus appear irreconcilable. But with Hegel one needs not fear contradiction. “Contradiction is the criterion of truth; non-contradiction, of falsehood”—so reads Hegel’s first habilitation thesis. Even the simple dialectical schema of thesis–antithesis–synthesis suggests that encountering contradiction is not a sign of error or a moment of “either-or” decision but rather a sign that thought is encountering truth. To express that truth, one needs only to synthesize these opposing positions—in this case, realism and Kantianism.

Hegel’s synthesis of progressivism and realism is perhaps most clearly expressed in the following passage:

Alone the state is individual, and in the individuality the negation is essentially contained. If therefore also a number of states forms itself into a family, then this club as individuality must create an opposition for itself and produce an enemy.

The progressive element lies in the insight that states do not interact like billiard balls but can genuinely recognize each other and form familial relations. Just as war is inconceivable within a family, conflict can become unthinkable within a family of nations. What at first appears to be a utopian ideal—friendship between states—turns out to be genuinely possible.

However, peace among friendly nations comes at a cost. The union of some necessarily involves the exclusion of others, and the excluded state is not merely left out but actively constructed as a potential enemy. This follows not from Hegel’s whim but from the very structure of individuality itself. Individuality, by its very nature, is exclusive.

An individual—whether a private person, a state, or a family of nations—constitutes itself by setting boundaries and distinguishing itself from an external other. Friendly relations within a family of nations stand in direct contrast to hostile relations beyond it. In relation to whom would individuality appear as individuality if it did not create a foreign counterpart for itself? Without defining itself against something external, individuality would dissolve like a drop in the ocean—and international politics would cease to exist altogether.

In other words, friendly or familial relations between a group of states are a precondition for the possibility of eventual global peace, but they are also the condition for its impossibility. Progress toward world peace does not encounter external obstacles but rather limits inherent in its very structure. The issue is not, as realists claim, that progress is impossible from the outset. Rather, because progress is genuinely possible, as Kant argued, it ultimately reaches the limits of its own continuation and gradually becomes impossible.

Today, we are witnessing the sobering truth of Hegel’s insight into how a family of states inevitably constructs its own enemy. The North Atlantic alliance, built fundamentally on mutual trust, is falling apart before our eyes, not because its members lack an enemy but because they are constructing different ones. NATO did not collapse immediately after the Cold War due to the disappearance of a common enemy, as some realists predicted, but only after approximately three decades as a result of divergent views of who is friend and who is foe.

Yet I do not believe the West is doomed; rather, the concept will become more refined when it is no longer narrowly tied to one country, the United States, but loosens into an ad hoc coalition of those willing to defend the international order.

Carr, E. H., The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 1919-1939 (2nd edn). New York: Harper & Row, 1946, p. 153.

Jaeschke, W., Hegel-Handbuch, Heidelberg: J.B. Metzler (3rd ed). 2016, s. 366.

Tomáš Korda is political scientist. He was a junior Jan Patočka fellow at the IWM in 2019.