“We must make sure that we remain in control of technology, and that technology does not assume control over us.”

IWM Rector Misha Glenny spoke these words on the occasion of 40th anniversary of the institute in 2022. Since then, the call for and urgency of democratic control over technology has become even stronger, especially in view of the explosive growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and other areas of what is generally referred to as the “digital transition” or the “digital transformation”. Being able to keep or regain control over technological developments requires a better understanding of the nature of, and the processes and forces involved in, technological innovation.

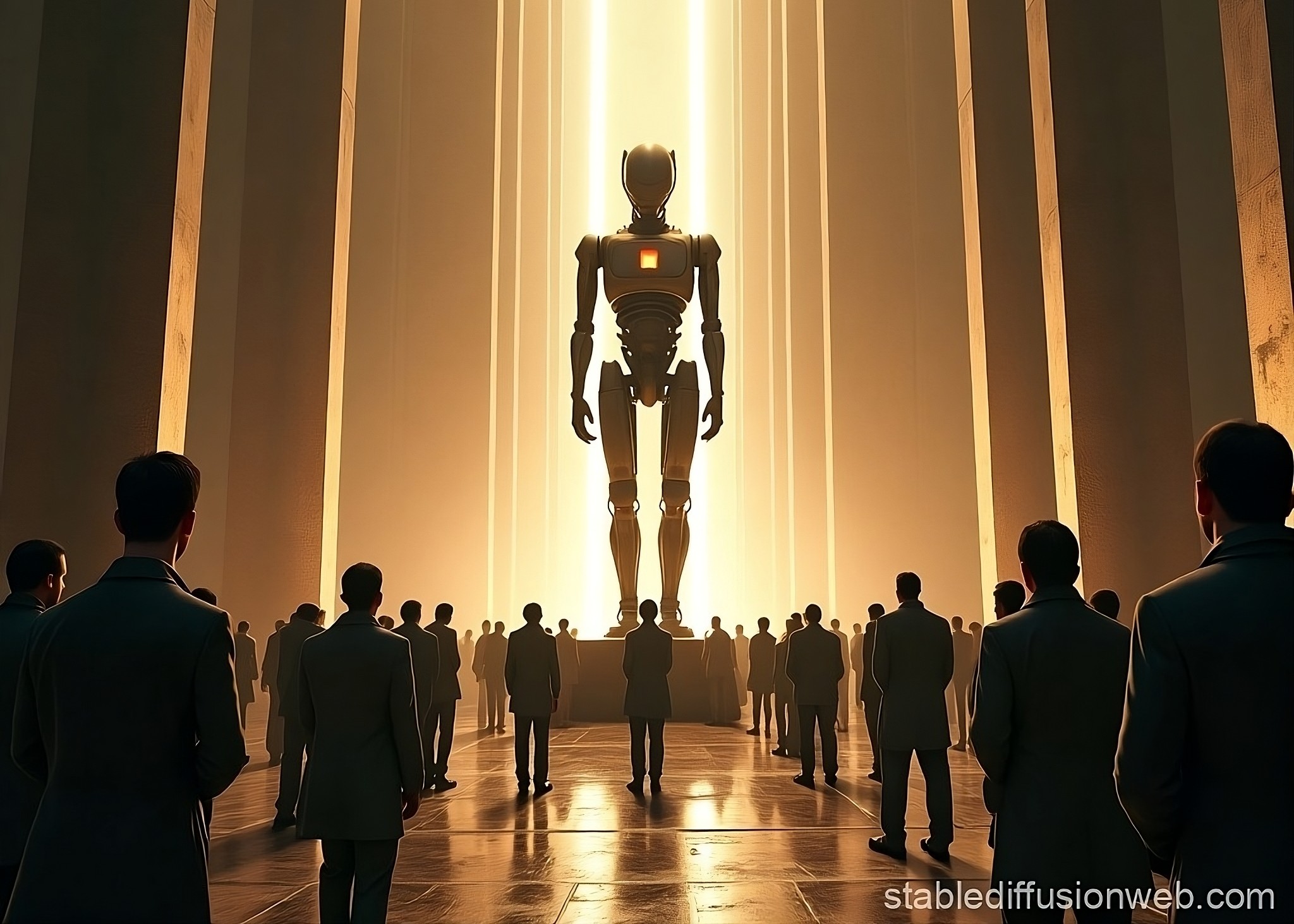

Images of Innovation

Innovation is a central tenet of policies worldwide, for governments and businesses alike. The traditional view is that it results from a chain of invention-adoption-diffusion processes: the classical linear model of innovation. This portrays innovation, and more generally progress, as a relatively mechanistic, deterministic, and unidirectional phenomenon—a view clearly inspired by the world picture of classical physics. The initial condition, invention, is typically portrayed as due to an individual act of a brilliant man (preferably a genius)—there is a cottage industry of glorifying hagiographies and hero histories about the likes of Nikola Tesla, Albert Einstein, Tim Berners-Lee, or Steve Jobs. The emergence of new technologies is seen as a relatively autonomous driving force.

The same linear view on innovation and progress appeared in the field of global development in the influential book The Stages of Economic Growth (1960) by Walt Rostow, adviser to US President John F. Kennedy. He postulated a uniform linear progression in five stages, from traditional society where most people live in rural areas as subsistence farmers, to industrialized advanced societies with high mass consumption. Interestingly, Rostow’s global development model claims descriptive and empirical scientific content as an economic theory, at the same time as it is explicitly and intentionally highly political: the subtitle of the book is A Non-Communist Manifesto, with the West and specifically the United States as the “hero”.

More recently, another model of innovation has made headway. In this, innovation is thought to result from an organizational ecosystem that produces it with the help of a “triple helix” supporting environment of companies, research and education institutions, and government.

The guiding metaphor of this innovation model is not classical mechanics but biological evolutionary systems. In contrast to the classical linear model, the ecosystem one recognizes that innovation is not a linear process and that multiple actors play a role, simultaneously competing and collaborating. The innovation ecosystem notion is abundantly present in the research and innovation programs of the European Union, but it also figures in the language of digital Big Tech companies.

Predatory and Extractive Business Models

Around the turn of the century, there were high hopes regarding the liberating and democratizing potential of the Internet and the Web. The ideas and hopes about Internet freedom have been mercilessly criticized in, for example, Evgeny Morozov’s The Net Delusion (2011), but it is too easy to belittle them as naïve utopianism. The new capabilities of global information and communication have provided instruments to create many grassroots interactive shared-interest communities, often by techno-enthusiasts—and they still have an impact. Creative Commons, Linux, Mozilla, and Wikipedia are among the best-known initiatives of this kind.

What might be called naïve is the underlying assumption that there is something inherent in a technology that makes it liberating or democratic, or not. This is an example of techno-solutionism, the idea that societal problems can be solved by purely technological means. Although quite common in technological innovation circles, techno-solutionism overlooks that technology is tightly embedded in an environment closely packed with all kinds of influencing social, economic, political, and cultural factors and forces. What is more, even if innovative technology has enabled steps forward in terms of democracy, freedom, human rights, or human flourishing, this does not necessarily imply that these are irreversible. Control over technology to some degree can change and shift, and it is subject to societal struggle.

This is what has happened with the advent of the platform and social-media Big Tech corporations. They have amassed monopolistic power, money, and control through business models that Shoshana Zuboff characterizes as surveillance capitalism. Big Tech business policies are also well characterized as digital land grabbing, data mining, and value extraction. In an in-depth analysis of many Big Tech business models, Roel Wieringa shows how these companies exercise tight manipulative control not only over their customers but also over the surrounding ecosystem of companies, with extremely high built-in profit margins. (Read his illuminating insights at https://www.thevalueengineers.nl/insights) He makes the important point that regulation and control of technology should be not so much about technology itself, but about disabling predatory and extractive business models.

Technologies of Governance

The Internet and the Web have long been seen as part of the family of information and communication technologies (ICTs). Today, however, one may wonder whether, in view of their further development by Big Tech in social media and platforms, it is not more accurate to see them, including AI, as technologies of governance of people.

Virgílio Almeida, Ricardo Fabrino Mendonça, and Fernando Filgueiras argue that algorithms should be viewed as digital institutions governing and controlling people’s behavior. These might do so the hard way (deny access; “Computer says No”) or the soft way (nudging social media users toward behaviors that algorithmically and opaquely optimize certain measures related to corporate profit). Jürgen Habermas similarly points out that a new structural change in the public sphere and deliberative politics is taking place. Recent political developments show that Big Tech’s economic market manipulation of consumers also enables new digital forms of political manipulation of citizens.

Despite its neutral technical imagery, innovation is prone to magical thinking. While recognizing the usefulness of certain parts of AI, Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor undertake a debunking mission in their book AI Snake Oil (2024), which “uncovers rampant misleading claims about the capabilities of AI and describes the serious harms AI is already causing in how it’s being built, marketed, and used in areas such as education, medicine, hiring, banking, insurance, and criminal justice.” Magical thinking occurs in innovation everywhere, but the two computer scientists single out AI for its history and culture of hype and unwarranted promises.

Current AI offers very good examples of magical thinking and myth-making. AI leaders recently told US lawmakers that more energy is needed if the United States hopes to win the AI race. Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt said environmental considerations should not get in the way of winning the AI race, arguing that AI will solve the climate crisis once the United States beats China in developing superintelligence. A few years earlier, Schmidt led the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence that argued that the United States has a moral imperative to develop AI autonomous weapons. The parallels with the militarization of nuclear power and the Cold War arms race are striking. In their propagandistic talk on achieving AI general superintelligence, Big Tech leaders display very distorted views of what it is to be human.

Control over technology calls for continuing scrutiny and debunking of technology snake-oil claims, and for building up relentless pressure for democratic and humanistic values that must be central to any technological development and innovation.

“AI Industry to Congress: ‘We Need Energy’”,The Washington Post, April 10, 2025.

“US has ‘moral imperative’ to develop Ai weapons, says panel”, The Guardian, January 26, 2021.

Hans Akkermans is professor emeritus of business informatics, and Steering Committee member of the Digital Humanism Initiative. He was a senior visiting fellow at IWM in spring 2025.

Anna Bon is senior international project manager, independent researcher and lecturer in information and communication technologies for development.