The New International Economic Order was a concerted attempt by the Global South countries to develop a framework for global economic relations based on equality and interdependence. Although it was ultimately defeated, revisiting it offers inspiration and hope for struggles in today’s world.

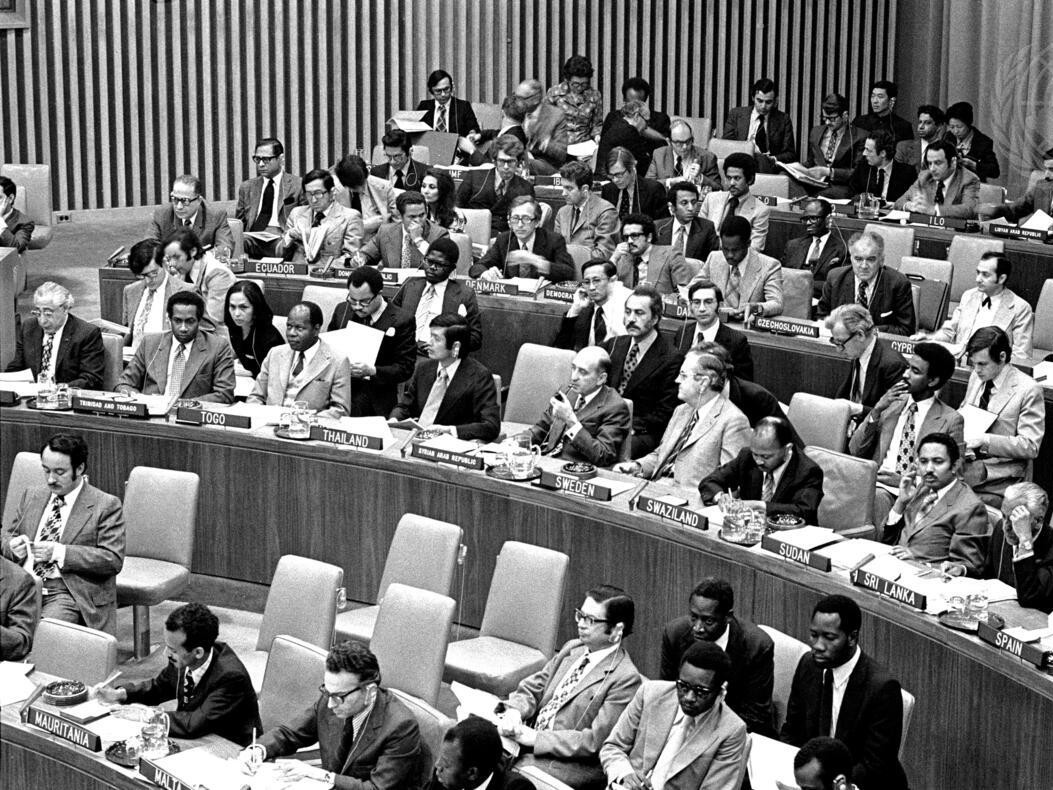

In 1974, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a declaration and program of action on a New International Economic Order (NIEO). This order was to be “based on equity, sovereign equality, interdependence, common interest, and cooperation among all states, irrespective of their economic and social systems which shall correct inequalities and redress existing injustices, make it possible to eliminate the widening gap between developed and developing countries, and ensure steadily accelerating economic and social development and peace and justice for present and future generations”.

The NIEO was a significant challenge to an unjust economic system based on colonial legacies and neocolonial exploitation in a world dominated by global capitalism and multinational corporations. It combined a concern with terms of trade with the right of developing countries to industrialize and diversify, in the context of the need for a new vision of development and a new architecture of global governance. Together with the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States adopted by the UN later that same year, which focused on the right to states’ sovereignty over their natural resources, including the right to nationalization, the NIEO was a significant challenge to the status quo. These two initiatives brought together in the political domain many elements that tended to be treated as completely separate. Perhaps more importantly, it was a moment when the countries of the Global South had a real voice in the global arena.

An NIEO of some kind was central to the work of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in the early 1970s. With East-West tensions abating, it turned more to questions of North-South inequalities and the need for a radical shift in global trade relations and global governance. The 1970 NAM summit in Lusaka, Zambia referred to “the poverty of developing nations” and their “economic dependency” as a structural problem of the global economic order. It called for rapid change in trade, finance, and technology. The NAM acted as a kind of Global South think tank, while the more formal Group of 77 developing countries acted as a kind of parliament of the Global South and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development provided technical expertise, particularly with regard to commodity prices. Arguably, however, what was crucial in providing the Global South with greater leverage was when, in 1973, members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries raised oil prices and limited supply in response to the war in the Middle East. This offered a new precedent. Algeria, in particular, sought to apply this approach to other commodities, raw materials, industrial goods, and the entire development agenda.

For several years, the countries of the Global South maintained a unity regarding the NIEO that was remarkable given their different views and interests. Global South political elites were strategic, maintaining outwardly a common front while having heated internal debates, discussing maximalist and minimalist demands, and recognizing the different interests of oil-producing and oil-dependant states. Toward the end of the 1970s, the United States and its core capitalist allies, like West Germany and the United Kingdom, became increasingly open in their opposition to the NIEO and most intransigent on matters of trade, having earlier appeared more conciliatory. The NIEO was marginalized in the early 1980s, not least as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan led a shift to a mix of “roll-back neoliberalism” at home and “roll-out neoliberalism” in the global arena. The Global South entered a capitalist-induced debt crisis.

The NIEO was flexible enough to be supported by more radical and more conservative states in the Global South. Its slogan of collective self-reliance could imply a delinking of the Global South countries from the hegemonic economic system or a relinking on terms that allowed for the creation of global markets free from distortions. At times, the NIEO was presented in a way that appeared to recognize the antagonistic interests of the Global North and Global South while at other times there was a suggestion that a new global economic and social contract was in the interests of the developed and developing worlds alike. The Soviet Union initially supported the NIEO in the context of the Cold War, but this changed as it recognized that the focus was as much on its neocolonial exploitation of the Global South as that of colonial and capitalist powers.

While, inevitably, the NIEO could not cover every matter of global importance, some omissions from it are telling. It did not directly refer to the gendered nature of the existing international economic order nor consider the gender dimensions of the new one being advocated. Migration received little attention, but when it was discussed the tension between opening the world to the free movement of labor and preventing the negative impacts of brain drain on developing countries became apparent.

One question of huge importance is whether the NIEO was a program for rapid growth, modernization, and industrialization for large parts of the world at a time when there was a growing understanding of planetary boundaries and limits to growth. Two years before the NIEO was passed, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm was a site of North-South contestation about which environmental concerns should be prioritized and, more importantly, the nature of the relationship between these concerns and issues of social and economic development. This was clearly expressed at the 1972 NAM Foreign Ministers Meeting, when it was stated that most environmental problems were irresponsibly created by the industrialized countries. At the same time, there were linkages made within the Global South that prefigured the importance of differential responsibilities, reparations, and even degrowth.

In what sense is the NIEO a form of “useful history,” a kind of “usable past,” relevant to the challenges of the present? In 2013, the academic Radhika Desai argued that the BRICS grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa presented the most important challenge by developing countries to Western supremacy since the NAM and the NIEO. Its expansion to 11 countries (BRICS+) and many initiatives regarding terms of trade, finance, de-dollarization, and development reflect how very different the balance of economic power is compared to 50 years ago. At the same time, BRICS, and in particular Chinese, visions of development tend to be extractivist, neocolonial, and exploitative—seeking to shape the rules of a new global capitalist order in these countries’ interests rather than more equitable forms of South-South cooperation. BRICS+ has the potential to shake the foundations of the current, hypocritical rules-based international order, but the precise forms this could take remain uncertain.

The Tricontinental Institute and the Progressive International have recently revisited the NIEO in the light of today’s realities. Both initiatives lack a clear road map regarding which forces may have the power to develop a meaningful new NIEO in a “projectified” world in which thousands of reports are written today and forgotten tomorrow. The tensions between radicalism and reformism and between global and regional initiatives, as well as the difficulties in securing and maintaining unity of purpose across the Global South and between states and grassroots movements, all of which was present in the original NIEO, remain intractable. The lurch to neoliberalism of many countries of the Global South has become firmly entrenched and worsened by President Donald Trump’s combination of protectionism, deglobalization, and promotion of a racist international world order. Despite pronouncements of a post-neoliberal order and a new multilateralism, how to take forward a new NIEO remains unresolved. The lessons of what was a significant historical moment, however, remain important.

Paul Stubbs is emeritus senior research fellow at the Institute of Economics, Zagreb. He was a guest at the IWM in 2025.