The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has generated talk of the urgent need to decolonize Russia. Yet inside the country, this discourse clashes with a long tradition of imagining Russia, itself an empire and a colonial power, as a colony of the West. A complex of ideas subsumed under the name of Eurasianism played a crucial role in shaping this tradition.

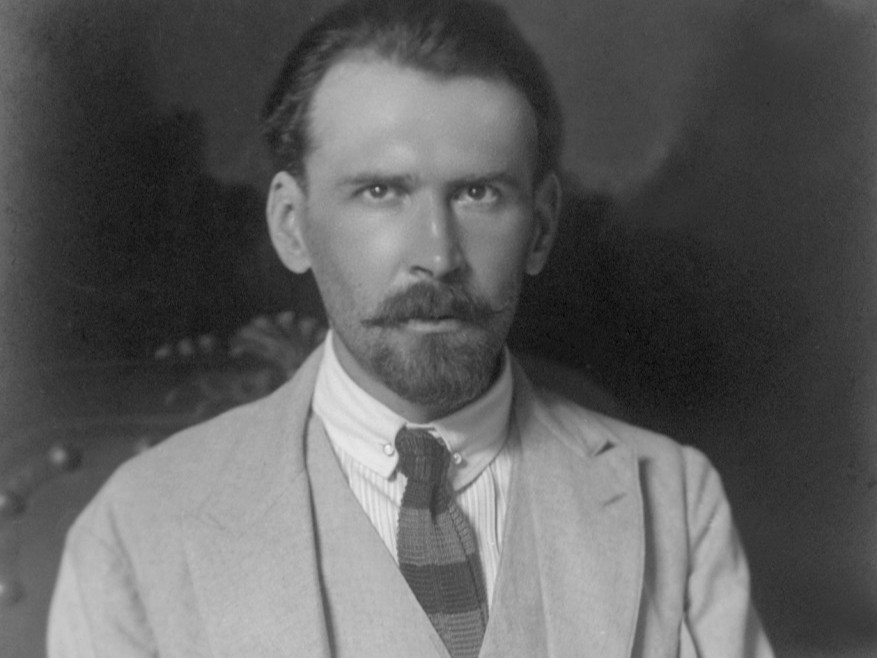

Eurasianism, a movement that emerged within the intellectual milieu of Russian émigrés in Europe in the early 1920s, is a fascinating, controversial, and highly paradoxical school of thought. Its imaginary, driven by a desire for recognition, sets local epistemes against the hegemonic Western discourse. The Eurasianists—a group of young Russian intellectuals whose leaders were Prince Nikolai Trubetskoi, Petr Savitskii, and Petr Suvchinskii—advanced core ideas of postcolonial theory. They vigorously attacked “egocentric” European chauvinism, called on non-Western intelligentsia to repudiate “evaluative judgement” of different cultures, and argued, 50 years before Edward Said, that colonial power is linked with and encoded in disciplinary knowledge. Yet their vision also contained a not very subtle imperialist agenda: it reimagined the Russian empire as an organic geopolitical, ethnographic, cultural, and linguistic entity—Eurasia—precisely with an eye to preserving the empire’s territorial integrity.

The political upheavals of 1917 dramatically changed Russia’s position in the global pecking order. Following two revolutions, the collapse of the monarchy, the disintegration of the empire, the effective defeat in the First World War, and the outbreak of civil war across the Eurasian expanse, Russia was lying prostrate, completely exhausted, helpless, and defenseless. By the end of 1920, the Bolsheviks had largely defeated all their political opponents. Most of the future Eurasianists were forced into exile and settled in the Balkans and Central and Western Europe. Young men in their late 20s and early 30s, scions of imperial noble families, highly educated and fluent in multiple European languages, they appeared to have lost everything—homeland, social status, prospects of successful self-realization—and ended up as wretched refugees in a hostile foreign environment, snubbed by haughty Europeans. No wonder that the perceived humiliation of Russia in the international arena coupled with their unenviable personal circumstances as social underdogs in Europe led the future Eurasianists to associate their country with the idea of colony and themselves with colonized peoples.

Two strong feelings dominated early Eurasianist anticolonial writings: visceral hatred of the imperialist West and compassion for and solidarity with the colonized nations of Africa and Asia. Three main themes stood out: the unmasking of the colonizer nations of Western Europe, the inevitability of Russia remaining a colony of the West, and Russia’s destiny to become the leader of the global anticolonial movement. However, the importance of resentment and the anti-West animus notwithstanding, Eurasianism as a complex of ideas was, first and foremost, a theory of nationalism and empire. The virulent critique of colonialism, Eurocentrism, Europeanization, cosmopolitanism, and civilizational hierarchies was an integral part of the Eurasianist doctrine, which sought to reimagine Eurasia as a geopolitical entity that was neither a Western-style colonial empire nor a nation-state but an organically formed commonwealth of brotherly peoples.

The Eurasianists’ anticolonial discourse was very ambiguous. While they sharply criticized the colonial nature of the Western European maritime empires, Russian colonialism in the Caucasus, Turkestan, the Far East, and other borderland regions appeared to have been their blind spot. This was not surprising: the multiethnic realm of the Romanovs, officially proclaimed an empire in 1721, was a colonial power in denial. The reason behind the reluctance of Russian imperial bureaucrats to acknowledge the colonial nature of the Russian empire was twofold. First, their social ideal was a unitary empire in which various ethnic groups would merge into a single whole, united by the feeling of dynastic loyalty, official patriotism, imperial citizenship, and high Russian culture. Second, Russian imperial government was wary of recognizing de jure the existence of its de facto colonial dependencies lest this encourage local nationalisms and separatist movements in the non-Russian borderlands.

The Eurasianists lived through the bloody drama of Russia’s imperial collapse. They also witnessed the disintegration of the other land-based empires that had been defeated in the First World War. In the post-imperial space, they saw the proliferation of local nationalisms and the emergence of many small countries that claimed to be national states. In postwar East-Central Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East, these processes were encouraged by US President Woodrow Wilson’s energetic advocacy of the principle of self-determination. In the territories of the former Russian empire, the Bolsheviks were busy constructing a complex hierarchy of national statehoods for the myriad ethnic groups that had very recently been subjects of the Russian tsar. The Eurasianists regarded the Wilsonian and Leninist policies alike as deeply flawed. They argued that nationalism, and especially that of small nations, could not act as an antidote to empire and colonialism because historically it was an organic product of European civilization, which styled itself not as a local but as a universal one. Thus any nationalism—essentially a movement of just one human collective that called itself a nation—would naturally claim some universal characteristics, which was fraught with the emergence of civilizational hierarchies, unequal power relations, and eventually a colonial situation in which some nations would lord over others. Likewise, the Eurasianists opposed the transformation of the Russian post-imperial space in accordance with the European model of a modern colonial empire in which a Russian “national center” would dominate colonial peripheries. From the Eurasianist perspective, the nationalism of small post-imperial nations and Russian imperial nationalism were the manifestations of the pernicious European hegemonic discourse and radically out of place in Russia.

What makes the Eurasianist anti-West and anticolonial discourse relevant today? One hundred years ago, a tiny group of talented young Russian émigré intellectuals assailed Western imperialist domination and came up with a powerful rhetorical antidote to the West’s hegemonic discourse that has since been used worldwide. The Western empire, the Eurasianists claimed, was a project of gradual absorption of all peoples and cultures into the global Western civilizational model. This process was being facilitated by the notion of universal human values embodied in Western civilization. The idea of progress and universal culture was turned into an ideological tool justifying the “white man’s burden” and a mission civilisatrice.

Having included Russia into a broad group of nonwhite colonized peoples whose affairs the Europeans sought to manage, the Eurasianists introduced into the Russia-Europe confrontation genuinely revolutionary motifs. As an alternative to the aggressive and exploitative Western colonial empire, they set forth a different imperial model: a Eurasian continental empire based on economic autarky and the organic geographical, historical, and ethno-cultural unity of Eurasia. The Eurasianist political imagination created a kind of anti-imperial empire in which the old conflict between national aspirations of Russia’s borderland peoples and the unity of Russian imperial space appeared to have been successfully resolved.

These ideas proved to be contagious. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and increasingly since the early 2000s, there has been a veritable Eurasia redux. Post-Soviet Russia has been struggling with a painfully familiar old question: how to become a full-blown subject of modernity and yet avoid finding itself in a situation of political and/or discursive dependence on the Euro-Atlantic world that claims monopoly on modernity? The suggested solution to this dilemma offered by Kremlin-friendly ideologues is an unmistakably Eurasianist one: a vision of Russia as a unique and distinct Eurasian civilization within a multipolar world without a hegemon—a “pluriverse” of self-contained civilizations, each with its own episteme or, as Russian conservative thinkers would term it, national cultural code.

Igor Torbakov is a senior fellow at the Institute of Russian and Eurasian Studies at Uppsala University. He was a visiting fellow at the IWM in 2025.