Europe’s public service media are increasingly struggling to maintain their relevance and legitimacy in today’s platform-dominated information environment. In many countries, they are also targeted by populist and illiberal actors seeking to undermine their independence. While demands for their reform are not without merit, their demise would only accelerate the deterioration of democracy and the public sphere.

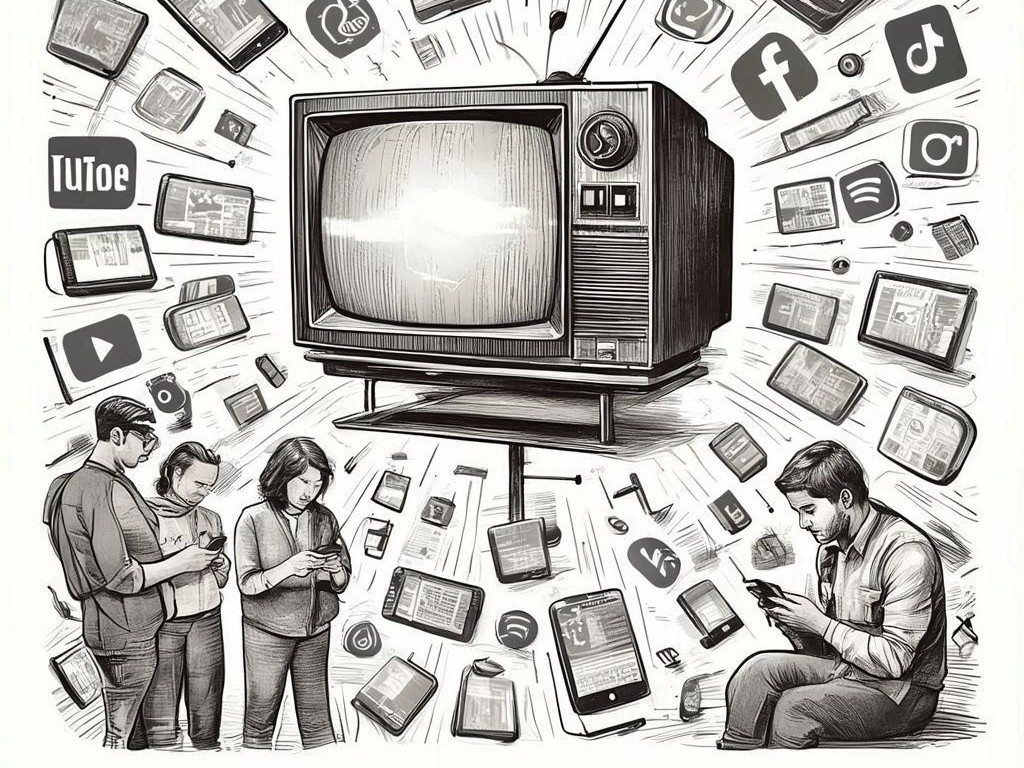

The world of media and communication is undergoing a profound transformation that is reshaping audience habits and redefining the media industries and the journalistic profession. The old system, dominated by traditional outlets and largely linear content, is being replaced by one in which global tech companies, digital platforms, and algorithmically personalized ecosystems have taken primacy, determining what kinds of information and entertainment people encounter. Social media are quickly becoming the leading sources of news for the population as a whole and not only for the youngest generations. Sharing platforms and streaming services such as YouTube, TikTok, and Netflix, rather than television channels, are now the most widely accessed providers of video entertainment. At the same time, news avoidance is on the rise, and when people seek news they turn ever more to influencers, podcasters, and other individual digital content creators instead of professional news organizations.

In light of such seismic shifts, public service media are increasingly deemed unfit for an age of (alleged) digital cornucopia, grappling with declining audiences and mounting financial pressures. In the United Kingdom, the media regulator Ofcom recently issued a warning that public television programming is “under serious threat” as it struggles to compete for audiences with global streaming platforms. The BBC, the world’s oldest and most famous public service broadcaster, has lost more than 300,000 license-fee payers in the past two years. This adds weight to calls for replacing the license fee with an alternative type of funding, though it is unclear what form this should take and whether the BBC would survive its introduction.

Elsewhere in Europe, public service media are also facing growing pressure to reform their funding models and other shared challenges. This includes countries with long-standing public broadcasting traditions—such as Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden—where outlets recently reported budget freezes or reductions, staff redundancies, mergers, and in some cases closure. According to the European Broadcasting Union, funding for public service media across Europe has declined by 11 percent in real terms over the past decade due to inflation, significantly undermining their long-term sustainability.

These media are also increasingly facing challenges to their independence. A 2025 report by Reporters Without Borders highlighted that in more than half of the EU member states public media are subject to political pressure and government interference, and sometimes to outright capture and use as instruments of government propaganda. Hungary has long been a textbook example of the latter form of interference as part of the country’s democratic decline under Viktor Orbán’s regime. Poland’s national broadcaster TVP faced a similar fate under the Law and Justice party government (2015–2023), and many observers fear that Slovakia’s will follow the same path under Prime Minister Robert Fico, whose reform of public service broadcasting has been widely seen as an attempt to tighten government control. In Czechia, this scenario is also possible under the new government coalition of populist and far-right parties that share deep-seated animosity toward public service media.

Political interference with the autonomy of public media is, however, not limited to Eastern European countries. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni’s government has been repeatedly accused of exerting pressure on the management of the public service broadcaster RAI, which, according to observers, has led to self-censorship, changes in programming, and suspensions of critical voices. In most countries in Europe, public service media and journalists are frequent targets of verbal attacks from populist and far-right parties that systematically try to erode public trust in them.

Whether due to the impact of digital technologies, the unfavorable economic environment, or control-seeking political elites, the century-old institution of public service media is entering a period of profound, potentially existential, crisis. Some welcome the prospect of its demise; others view it as historically inevitable. In this context, its preservation will depend on finding new and convincing ways to justify its continued relevance.

Arguments in defense of public service media usually invoke the roles and missions traditionally assigned to them: above all, to inform, educate, and entertain without yielding to commercial or political interests; to nurture national culture and identity; and to represent and cater for all segments of society. While these are all arguably important and worthy objectives even in the digital age, at least some of them are now also being fulfilled by other types of media and communication platforms, particularly those operating online. In an era of information abundance, experienced through a plethora of websites, social networks, and streaming services covering all possible genres and formats, it feels ever more challenging to claim that safeguarding pluralism, ensuring access to quality content, and providing adequate cultural representation in the public domain requires the protection of a single privileged institution.

The case for public service media must therefore be built on different grounds. It must accept a narrowing of their remit within today’s digital communication ecosystem, particularly in the cultural sphere, while counterbalancing some of the impacts of digital platforms that increasingly undermine democracy and the public sphere. Phenomena such as deepening polarization, the spread of disinformation and hate speech, and the erosion of trust in institutions cannot be attributed solely to the rise of platforms, yet they are undoubtedly amplified by them. And, although it might be possible to mitigate some of the most harmful manifestations of algorithm-driven platform capitalism, regulation is unlikely to eliminate them completely, as they are embedded in the very architecture of these technologies.

Public service media cannot serve as a cure-all for all these challenges. But they can offer an alternative communication environment grounded in values and qualities that are increasingly falling out of fashion amid the rise of selective exposure, partisanship, and the echo chambers that proliferate in the digital world—journalistic professionalism, fairness, and impartiality; an uncompromising commitment to facts, truth, and evidence-based knowledge, in contrast to the epistemological populism of social media and the clickbait attention economy in which misinformation thrives; and the provision of a space for civil exchange and contestation among differing political opinions, free from the commercial imperative to provoke conflict.

There is no guarantee that by merely championing these principles and positioning themselves at the forefront of the struggle for democracy’s future, public service media will secure their own survival. To remain relevant in the digital environment, they must adapt to it while resisting its harmful impacts. This will not be possible without adequate funding and meaningful collaboration with digital platforms, which will likely require new policies and regulatory measures at the national and European levels. It may be a difficult mission with uncertain outcomes but, given the stakes, it is one worth pursuing.

Václav Štětka is professor of media and political communication at the Department of Communication and Media, Loughborough University in the United Kingdom. He was a guest at the IWM in the autumn of 2025.