We know relatively little about intra-familial ruptures in National Socialist Germany. Most well researched are the divorces of Jewish-non-Jewish marriages, many of which were brought about by means of coercive measures. But what about those non-Jewish families whose individual members found themselves on opposite sides of the political divide? Were there, for example, cases of National Socialists and communists or social democrats within the same family?

Divergent Career Paths

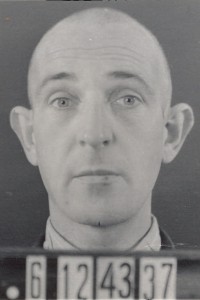

The Filbert brothers, who are the subject of this article, were both born in Darmstadt in the then Grand Duchy of Hesse, Otto on 10 May 1904 and Karl Wilhelm Alfred, known as Alfred, on 8 September 1905. Their father was a career soldier and company sergeant major. After obtaining his secondary school certificate, Alfred began an apprenticeship at the Commerz- und Privatbank in Mannheim on 1 April 1922. The blockade of the bridges across the river in the French-occupied Rhineland caused him to discontinue his apprenticeship in Mannheim and instead complete it at the Rheinische Kreditbank in Worms. Following the completion of his apprenticeship, Alfred was unable to find employment in a bank due to the prevailing economic crisis. After a stint helping out in the tax office in Worms, he decided to return to school in order to sit his school-leaving examinations so as to be hired afterwards by the tax office as a salaried employee. After attending a private school in Mainz for a year and a half, he sat his school-leaving examinations at Easter 1927. Instead of seeking employment at the tax office, his father allowed him to study law at university. He enrolled for the summer semester 1927 at the Hessian Regional University in Giessen, where he passed the First Legal State Exam with the overall grade of “sufficient” at the end of December 1933 and became a Doctor of Laws in February 1935 with a thesis on bankruptcy law.

The Filbert brothers, who are the subject of this article, were both born in Darmstadt in the then Grand Duchy of Hesse, Otto on 10 May 1904 and Karl Wilhelm Alfred, known as Alfred, on 8 September 1905. Their father was a career soldier and company sergeant major. After obtaining his secondary school certificate, Alfred began an apprenticeship at the Commerz- und Privatbank in Mannheim on 1 April 1922. The blockade of the bridges across the river in the French-occupied Rhineland caused him to discontinue his apprenticeship in Mannheim and instead complete it at the Rheinische Kreditbank in Worms. Following the completion of his apprenticeship, Alfred was unable to find employment in a bank due to the prevailing economic crisis. After a stint helping out in the tax office in Worms, he decided to return to school in order to sit his school-leaving examinations so as to be hired afterwards by the tax office as a salaried employee. After attending a private school in Mainz for a year and a half, he sat his school-leaving examinations at Easter 1927. Instead of seeking employment at the tax office, his father allowed him to study law at university. He enrolled for the summer semester 1927 at the Hessian Regional University in Giessen, where he passed the First Legal State Exam with the overall grade of “sufficient” at the end of December 1933 and became a Doctor of Laws in February 1935 with a thesis on bankruptcy law.

Otto took a very different path, both professionally and in his life in general. In April 1926, aged not yet 22 years, he immigrated to the United States of America, where he became an engineer at the Pullman Works in Philadelphia. In 1933 he married Wilhelmina Koskamp, who was also German and had immigrated to the USA only two months after Otto. Otto’s parents persuaded him to come back to Germany in 1938 with his wife and their two sons on a one-year trial basis. Unable to adapt to the new way of life in Nazi Germany, Otto resolved to return to the United States. As he was still a German citizen, however, he was refused permission to emigrate. Following the failure of the assassination attempt on Hitler’s life made by Georg Elser on 8 November 1939, out of bitterness Otto commented to a colleague at the Junkers Aircraft Factory in Dessau: “Pity that the scoundrel didn’t perish.” Denounced by his colleague, Otto was promptly arrested by the Magdeburg Gestapo and sentenced to four years imprisonment for “malice”, although he did not have any previous convictions.

Otto took a very different path, both professionally and in his life in general. In April 1926, aged not yet 22 years, he immigrated to the United States of America, where he became an engineer at the Pullman Works in Philadelphia. In 1933 he married Wilhelmina Koskamp, who was also German and had immigrated to the USA only two months after Otto. Otto’s parents persuaded him to come back to Germany in 1938 with his wife and their two sons on a one-year trial basis. Unable to adapt to the new way of life in Nazi Germany, Otto resolved to return to the United States. As he was still a German citizen, however, he was refused permission to emigrate. Following the failure of the assassination attempt on Hitler’s life made by Georg Elser on 8 November 1939, out of bitterness Otto commented to a colleague at the Junkers Aircraft Factory in Dessau: “Pity that the scoundrel didn’t perish.” Denounced by his colleague, Otto was promptly arrested by the Magdeburg Gestapo and sentenced to four years imprisonment for “malice”, although he did not have any previous convictions.

Nazi Career and Mass Murder

At the time of the arrest of his brother in November 1939, Alfred Filbert held the SS rank equivalent to a lieutenant colonel and was deputy head of Office VI (SD Overseas) in the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA). How had this come about? Already during his university studies he had joined the Nazi movement. On 23 August 1932 he had joined the SS in Worms and a few days later the NSDAP. The head of his SS sub-unit wrote about him in an appraisal from October 1933: “During the heavy fighting on Shrove Tuesday of this year he was in the front line.” After passing the First Legal State Exam at the end of 1933, he had admittedly commenced his legal traineeship for junior lawyers at the end of January 1934, but as early as October 1934 he had successfully applied for leave from the traineeship. At the same time he had applied to the Security Service (SD) of the Reichsführer-SS and been appointed as a full-time employee in the SD Main Office in Berlin on 1 March 1935. After extending his leave several times, he was permanently discharged from the legal traineeship at his own request in November 1938.

How did the arrest and conviction of his only brother impact both professionally and personally on Alfred Filbert? His rapid ascent within the SD apparatus came to a halt. In spite of five promotions in the SS within the space of two and a half years up to the end of January 1939, he would not be promoted again. This halt to promotions was clearly a result of the arrest of his brother. Although Alfred had allegedly visited his brother on several occasions in Dessau Prison, the fate of his brother led in no way to a practical or even an internal rejection of National Socialism. On the contrary: in spring 1941 Alfred volunteered for the forthcoming deployment of SS Einsatzgruppen in the campaign against the Soviet Union. He was commissioned with the command of Einsatzkommando 9 within Einsatzgruppe B in the central operations zone of the eastern front. During his four-month stint in the east, he proved to be one of the most radical executors of the genocide of Soviet Jewry. His commando was the very first to commence with the systematic murder of women and children at the end of July 1941. By the time he returned to Berlin on 20 October 1941 his commando had killed more than 16,000 Jews in Lithuania and Belarus. It was as if, in response to the imprisonment of his brother, he wanted with his zeal to prove to the RSHA and SS leaderships his commitment to the National Socialist cause and his ideological reliability.

House Arrest – Concentration Camp

Although in the eyes of the regime he had distinguished himself exceptionally in the east, upon his return to Berlin Alfred Filbert was accused of embezzlement and bribery. He had supposedly kept back 60,000 Reich marks in foreign currency in his office safe for his own personal use. It was furthermore claimed that he had taken out a dubious loan for the purchase of a house in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee. The interest rate agreed on for the mortgage was supposedly half a per cent lower than the rate generally applied. An SS court in Berlin initiated proceedings against him and he was suspended from duty in the RSHA. At the end of 1941 the two brothers, despite their very different prehistories, found themselves in not dissimilar situations: Otto was still in Dessau Prison and Alfred was under house arrest. This constellation lasted for approximately two years. By the end of 1943, however, the deck would be thoroughly reshuffled.

In December 1943 things turned even worse for Otto Filbert. After he had served his four-year sentence, he was admittedly released from Dessau Prison, though not allowed to return home: instead he landed in Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar. He was delivered there on 6 December by the Magdeburg Gestapo as a “political prisoner”. A few weeks earlier Alfred Filbert had been completely rehabilitated following his two-year suspension from duty and reappointed to the RSHA, though not to SD Overseas, as before, but to the Reich Criminal Police Office. There he again served under Arthur Nebe, his former superior with Einsatzgruppe B. The accusations against him were probably baseless, which is why there is no entry in the box “SS penalties” in his SS personnel file. It is far more likely that he was suspended because of his longstanding association with Werner Best and Heinz Jost, both of whom also came from Hesse and had fallen out of favour with Reinhard Heydrich.

War Merit Cross – Penal Unit

On 4 July 1944 Alfred Filbert was promoted to the head of the newly created group Economic Crime within the criminal police. This appointment was somewhat ironic in view of the charges brought against him less than three years earlier of misappropriation of funds and bribery. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler furthermore conferred on him the War Merit Cross 1st Class with Swords on 12 September. Alfred Filbert had evidently succeeded in regaining the favour of the RSHA and SS leaderships since his suspension from duty.

Things were very different for his brother. On 28 November 1944 Otto’s wife, Wilhelmina, received what would be her final message from her husband. On the same day Otto was released from Buchenwald concentration camp but transferred to the notorious SS Storm Brigade Dirlewanger. Over the former concentration camp inmates, who had been recruited by force, the commander of the unit, SS Lieutenant Colonel Dirlewanger was permitted to exert power over life and death, even in non-combat situations. Following rudimentary military training, the political concentration camp inmates were sent with the rest of the unit to the Hungarian front. During the course of hostilities, almost five hundred of the political prisoners succeeded in deserting to the advancing Red Army. Whether Otto was among the deserters can no longer be determined. It is just as likely that he had already fallen victim to the brutal treatment within the unit or the hostilities. In any case, he never returned to his family. On 16 May 1951, Otto’s widow applied to the relevant court for him to be declared dead as of 28 November 1944. On 15 October the local court in Bottrop declared Otto Filbert dead and – in the absence of more exact data – gave the evidently fictitious date and time of death as midnight on 31 December 1945.

Disappearance, Reintegration and Prosecution

At the end of the war Alfred Filbert succeeded in going into hiding and lived until April 1951 under the false name “Alfred Selbert” in the town of Bad Gandersheim in Lower Saxony. This period was then followed by a sixth-month stay with his sister in Mannheim, after which Filbert moved to Hanover, where he was able to make use of his commercial expertise to obtain a job with the Braunschweig-Hannoversche Hypothekenbank. Two years later his wife Käthe and their two sons joined him and they lived together in Hanover. Filbert quickly climbed the career ladder with the bank and was appointed manager of its West Berlin branch on 1 January 1958.

For a little over a year he was able to enjoy this new ascent. On 25 February 1959, at 7 o’clock in the morning, Alfred Filbert was arrested in his apartment at Bamberger Strasse no. 49 in Berlin-Schöneberg by two members of the West Berlin criminal police. On the next day he was charged with the murder of an unknown number of people of Soviet citizenship. Twenty-eight months later, after an eighteen-day trial, the Regional Court in Berlin sentenced Filbert on 22 June 1962, twenty-one years to the day since the German invasion of the Soviet Union, to life imprisonment for murder. The court concluded that Filbert had acted “from base motives and with forethought” and furthermore that he had “striven to have shot all Jews he could possibly get hold of and that he acted inhumanely towards the Jews”. On 9 April 1963 the West German Federal Supreme Court rejected Filbert’s appeal and thus confirmed the verdict against him as legally binding.

In light of the judgement passed against him, the Justus Liebig University in Giessen stripped Filbert of his Doctor of Laws title on 15 January 1964. Filbert vainly lodged an objection to the decision. In his four-and-a-half-page statement he portrayed himself as a victim of the regime. Due to the arrest of his brother by the Gestapo, Himmler had decreed “in the context of kin liability first of all a halt to promotions, surveillance and in 1941 deactivation from my duties and the takeover of a task force in the Russian campaign”. As a result of his “particularly difficult position owing to my brother” he allegedly had to carry out the orders. He concluded by counting himself among those who had suffered grave injustice at the hands of the Nazi regime: “The great injustice of the time, under which my family also had to suffer, will not be rectified by committing further injustice.” All this self-pity was of no use; his doctor title remained revoked.

As early as thirteen years after the judgement of the Regional Court in Berlin, the enforcement of the custodial sentence against Filbert was suspended. Following an examination, an eye specialist concluded that under the prevailing circumstances Filbert was threatened with blindness in the near future. On 5 June 1975 he was released from Berlin’s Tegel Prison.

“My brother was in Buchenwald and he is dead”

The almost seventy-eight-year old Filbert demonstrated his physical fitness in summer 1983 during the shooting of the feature film Gun Wound – Execution for Four Voices. Thomas Harlan, the son of Veit Harlan, the most prominent film director of the Nazi period, directed, whilst Filbert appeared in the lead role of the SS mass murderer “Dr S” and thus effectively played himself – Filbert had gone into hiding after the war under the name “Dr Selbert”. The film was premiered at the Venice International Film Festival in August 1984 together with the documentary film Our Nazi by the American director Robert Kramer, which had been shot simultaneously to document the making of Gun Wound.

At one point in Our Nazi the viewer sees how Harlan initiates a conversation with Filbert concerning a massacre of one hundred Jewish men in Belarus in August 1941, which Filbert had personally led. Harlan remarks that two men succeeded in fleeing the shooters of the task force and escaping. The viewer sees how Harlan briefs a group of six Jewish men. Filbert denies to Harlan his participation in the massacre and refuses to discuss the matter further. He stands up and attempts to leave the film set; a physical confrontation ensues. Filbert is confronted by the men briefed by Harlan, Holocaust survivors, one of whom may or may not be one of those who fled the massacre. One of the men shows Filbert a tattoo on his arm, which he says is from Auschwitz, where his entire family was murdered. Filbert replies: “My brother was in Buchenwald and he is dead.”

It was not the first time during the shooting of Gun Wound that Filbert had presented himself as a victim on account of the fate of his brother. On another occasion he explained his imprisonment not as a result of the atrocities he had committed in Lithuania and Belarus but instead as a result of his brother expressing regret at the failure of the attempt on Hitler’s life in November 1939: “I had to as a result of my brother, as a result of this statement [following the attempt on Hitler’s life], I had to sit in prison for 18 [sic] years. I lost my eyesight in the process, I lost my honour, the nervous strain. Yes, thanks a lot!” In Filbert’s eyes, it was “a crime under constraint”. On another occasion he weeps whilst talking about the fate of his brother. It initially appears to the viewer that Filbert’s show of emotion is on account of the suffering and death of his brother, before it becomes clear that he is in fact weeping – at least in part – for himself and his damaged career in the SS: “I naturally suffered a lot from this.”

The fate of his brother became a constant and crucial factor in Filbert’s post-war portrayal of himself as a victim. Not only his self-portrayal but also his self-perception appears to have been decisively and lastingly shaped by the incarceration and death of his brother. He did not regard himself as a perpetrator but as a victim, who through no fault of his own found himself in a hopeless situation with no way out and was forced to commit terrible deeds. In Filbert’s case, the decision and motivation for partaking in mass murder, which occurred after the imprisonment of his brother, are thus particularly illuminating. Alfred Filbert died on 1 August 1990 in Berlin at the age of 84 years. His two sons live in Berlin and Stuttgart, respectively. They have close contact to the sons of their uncle Otto.

Alex J. Kay holds a PhD in Modern and Contemporary History from the Humboldt University, Berlin. He is author of Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder: Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940–1941 (Berghahn 2006, paperback edition 2011) and contributing co-editor of Nazi Policy on the Eastern Front, 1941: Total War, Genocide, and Radicalization (University of Rochester Press 2012). He received the Journal of Contemporary History‘s George L. Mosse Prize for 2006. In 2008 he presented at a conference at the IWM as part of the United Europe – Divided Memory project.