Birth Certificate is a book about one writer’s obsession with another writer. The author, Mark Thompson, is a British historian of Yugoslavia. Danilo Kiš was a Yugoslav novelist, as well as the translator of Anna Akhmatova from Russian, Endre Ady from Hungarian, and Raymond Queneau from French. He was a Hungarian Jew, a Montenegrin, and an Orthodox Christian—an “ethnographic rarity” that he believed would die out with him.

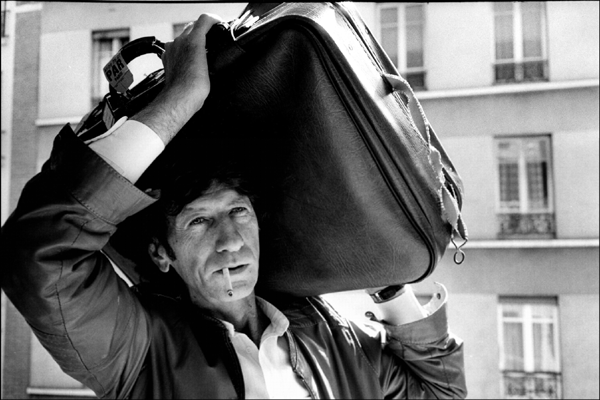

Kiš’s father was a Hungarian Jew. His mother was a Montenegrin Christian, descended from warriors. Kiš’s Montengrin ancestors, unafraid of chopping off the heads of Turks, represented everything Central European Jewry was not. Montenegro was clans, blood, honor and revenge. Jewishness was liminality, wandering, homelessness, anxiety. Kiš, born in 1935, spent his first seven years in the Yugoslav town Novi Sad, then the following five years in his father’s birthplace, the Hungarian Catholic village Kerkabarabás. His father drank, his mother knitted, Danilo cleaned henhouses. Later he studied violin in Montenegrin Cetinje before going on to study literature in Serbian Belgrade. There in the postwar Yugoslav capital, a city with so few cars there were no traffic lights, Kiš became an urban cosmopolitan, a bohemian café intellectual, a chainsmoking guitar player prone to brawls, a novelist who wrote by day and drank by night. Impoverished, passionate, sentimental about songs and disciplined about literature, Kiš lived in twentieth-century Belgrade much as Dostoevsky’s heroes did in nineteenth-century Petersburg.

Kiš was an anti-communist. He was also an anti-nationalist. Thompson describes him as “a man of liberal convictions and violent emotions”—an ideological-temperamental combination perhaps only slightly less rare than the ethnographic one. The hollowness of nationalism was glaring: as a Jew who had lived in Hungary, Montenegro and Serbia, Kiš could not help but notice the “relativity of all myths,” the mimetic doubling, the ways in which national legends invariably resembled one another. “The nationalist fears no one,” Kiš wrote, “‘no one but God’. Yet his is a God made to measure, his double sitting at the next table, his own brother, every bit as impotent as himself.”

Literature—the best kind—Kiš saw as an antidote to nationalist myth and a transcendence of oppressive particularity. In Kiš’s words, literature meant “an attempt at a global vision of reality;” in Thompson’s words it meant “salvation from the overpowering specificity of his own experience and the multiplicity of his ethnic identities.” Kiš was a writer of that “Central Europe” so poignantly evoked by György Konrád, Milan Kundera, and Czesław Miłosz. “A mythic name for several kinds of nostalgia,” as Thompson describes it, “Central Europe” expressed a longing for Europe tout court.

But Europe in the twentieth century was a bloodbath. Kiš was six years old on the day in January 1942 when the temperature dropped to minus 30 degrees Celsius and the Nazi-allied Hungarian military controlling Novi Sad took hundreds of Jews and Serbs to the bank of the Danube, forced them to strip, and then shot them—naked and frozen—in groups of fours, pushing the corpses through holes blasted in the ice. Eventually the corpses clogged the holes. The shooting was paused; Kiš’s father survived. Afterwards Danilo, his sister, and their parents fled Novi Sad, traveling for days by sleigh through what Kiš described as “a snowy wasteland, blank as the ocean.” Finally they arrived at the village in southwestern Hungary where there still lived Kiš’s paternal relatives, the only Jews in the village.

In 1944 the Nazis came to Hungary and took Kiš’s father to Auschwitz. The obsession with his father’s death shaped Kiš’s entry into the world of literature. “Nobody,” Thompson writes of Kiš, “did more to prove that Europe’s twentieth-century experiments in fiction can take the measure of its experiments in totalitarianism.” This was not because Kiš followed his father through the gates of Auschwitz. On the contrary: he refused. He felt revulsion at the possibility of kitsch. He reigned in raw emotion with irony and restraint. Kiš grew into a modernist writer who felt keenly what Pericles Lewis has described as the “crisis of representation.” Kiš’s obsession was to imbue totalitarian hell with the “grace of form” that might allow meaning and order to emerge from chaos.

The modernist novel—epitomized by James Joyce’s Ulysses—probed the mystery of interiority. Kiš’s polyphony, his defamiliarized doubles suggested the simultaneous impossibility and necessity of identity. Identity was both a modernist problem and a modern one: alienation belonged to the modern condition. This was true all the more so for exiles.

In 1979 Kiš made Paris his permanent residence. In France he refused to be tamed. “Kiš never grasped,” Thompson writes, “that a lapse of manners in the West can be unforgivable.” His failure to adjust to Western manners perhaps belonged to a failure to accept more generally the repression that is, Freud told us, civilization.

It was Freud’s idea of Unheimlichkeit that Kiš considered to be his “basic literary and metaphysical stimulus.” The untranslatable German Unheimlichkeit suggests “the uncanny,” the condition of not-being-at-home. For Freud (as, famously, for Heidegger) Unheimlichkeit was inextricable from nothingness, anxiety, the inevitability of death. Thompson’s penetrating discussion reveals how for the bereft Kiš—who as a child lost his father, as a teenager lost his mother, and as a grown man was condemned by infertility to childlessness—it was awareness of death that illuminated subjectivity. “The suffering was hideous,” Kiš wrote. “A kind of ‘metaphysical fear’, fear and trembling. All of a sudden, with no visible exterior cause, the defense mechanism that lets you live with the knowledge of human mortality goes to pieces, and a menacing lucidity comes over you—an absolute lucidity, I could call it.”

Quotations such as this form part of the rich intertextuality of the book. Birth Certificate is not a traditional biography. It is, rather, a formal literary experiment about an experimenter in literary form. Kiš’s very short autobiographical text, written in 1983 and titled “Birth Certificate,” provides the conceit: Thompson’s book is an annotation of and gloss on Kiš’s original “Birth Certificate.”

Thompson’s book is carefully crafted. The depth of the research is something special. At moments the vocabulary is almost too luxurious, the writing almost too artful. As a whole the book is a bit daring, a bit pretentious, and utterly sincere. Thompson interweaves biography and literary analysis perhaps as seamlessly as has ever been done.

Danilo Kiš died of lung cancer in 1989. His death immediately preceded the vile and gruesome breakup of his country. Like Kiš, Thompson offers no redemptive teleology. Yet Thompson’s formal experiment does not conclude in nihilism. Throughout his creative searchings, Kiš—Thompson shows us—declined to cross the border from modernist experimentation with narrative to post-modernist skepticism of narrative’s very viability. For Kiš there was always the faith that the right form might be found. For Thompson, too, grappling with Kiš’s tragic life, there is a hard-won metaphysical triumph: storytelling is still possible.

Mark Thompson, Birth Certificate: The Story of Danilo Kiš, Cornell University Press 2013

Marci Shore is Associate Professor of History at Yale University and a Visiting Fellow at the IWM. Her most recent book is The Taste of Ashes: The Afterlife of Totalitarianism in Eastern Europe.

Read also: “Durable Fiction. Danilo Kiš and His Library” by Aleš Debeljak, in: IWMpost 112, p. 21.