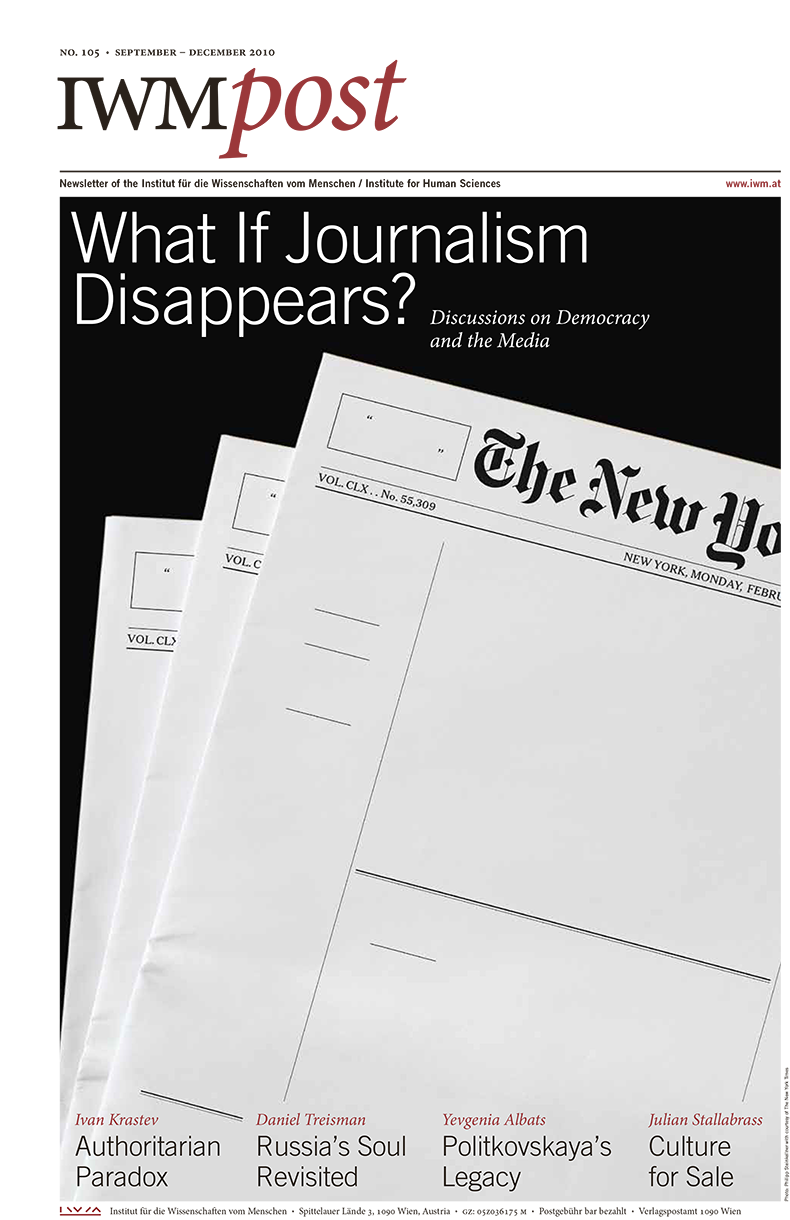

What we know about the world we live in, we know through the media. 9/11, climate change or the financial breakdown—we watched it on TV, heard it on the radio or read about it in the newspapers and on websites. But the media is not merely a passive recorder of events, it is rather the public’s eyes and ears. Watergate and Wikileaks are just two examples of the media’s crucial role as a „watchdog“ that monitors governments and exposes wrongdoings. The press as the „fourth estate“ is therefore an essential part of democracy. However, press freedom has increasingly been exposed to pressure. On the political level by Berlusconian or Murdoch-style media moguls or—as recently in Hungary—by restrictive new media laws; on the economic level by steadily dropping circulations and a culture of freebie journalism. How the media influence our democracies and how they, in turn, are influenced by political and economic interests was at the center of a debate held at the Vienna Burgtheater and an international conference. You can find reports of what was discussed there on pages 4 onwards. The good news: independent journalism will not disappear. The bad news: its independence cannot be taken for granted anymore.

The latter held of course always true for Putin’s so-called “sovereign democracy”. Russia is at rank 140 in the “2010 Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index”. In a speech at the Austrian Parliament on October 6, the Russian journalist Yevgenia Albats commemorated her fellow reporter Anna Politkovskaya, who was assassinated four years ago. In her contribution on page 23, Albats describes the threats, harassments, and assaults that critical journalists are facing in Russia today.

But it is not only control of public opinion that helps authoritarian regimes to survive. The new authoritarianism offers an emergency exit: who doesn’t like it here can simply leave—and that’s exactly what two million Russians did in the last decade. But with the well-educated middle class leaving the country instead of pushing for reforms, it is strengthening the regime that it rejects, observes Ivan Krastev on page 18.

While for him the glass of democracy in Russia seems half empty, Daniel Treisman sees it half full (on page 17). He claims that Russia is not on its way back to Soviet times but in the middle of a transition process. In the end, it will be a normal democracy with freedom of press and of opinion. When this will finally come true we will presumably learn from the media, and hopefully from the Russian journalists themselves.

Sven Hartwig

Download the IWMpost 105 as a PDF

Content

European Debates

In Search of Europe

Platform Agnostics and Cathedral Builders

Bad News for the News / by Paul Starr

Journalism That Matters / by Bodo Hombach

Conference on Democracy and the Media

Troubles in the Newsroom

The Watchdog Barks Online / by Sheila S. Coronel

Europa im Diskurs

Is Big Brother Watching Us?

Lectures and Discussions

Puzzling Identities — IWM Lectures in Human Sciences

Shared Responsibility — Jan Patočka Memorial Lecture

Secularity in China, Contemporary Capitalism, Narrating Space — Monthly Lectures

Chinese Climate, European Leadership — Lecture Series

Representing Reality, Branding Culture, Powerful Objects — Lecture Series

Life Sciences in Context — Conference

Violence and Acknowledgement — Workshop

Emotional Capitalism — Workshop

Challenging Authorities — Junior Visiting Fellows’ Conference

Digitalizing History — Presentation

Russia’s Press Perils — Anna Politkovskaya Memorial Lecture

Conservatism and Populism — Tischner Debate in Warsaw

Summer School

God Is Not Dead

Essays on Eastern Europe

The Invisible Minority / by Gerhard Baumgartner

Beyond Horror and Mystery / by Daniel Treisman

From the Fellows

Authoritarianism 2.0 / by Ivan Krastev

Fellows and Guests, Varia

Publications

Guest Contributions

Selling the Museum / by Julian Stallabrass

Leaving Fear Behind / by Yevgenia Markovna Albats