This regional platform brings together a very diverse group of countries, 11 European Union (EU) countries and 5 non-EU, from the Baltics to the Balkans. Concentrated on trade, investment, and transportation networks, 16+1 supports Beijing’s diversified strategy in Europe by allowing it to focus capital investments for strategic assets and new technologies in the core EU countries, complemented by large infrastructure projects on its periphery.

The geo-strategic position of the Western Balkans is perfect as a bridgehead to EU markets, and a key transit corridor for the Chinese BRI. Chinese interests in the region are strongly related to infrastructure projects and privatization opportunities, where demand for preferential lending is high and acquisition prices are low. Beijing is also searching for new markets to expand its exports and strategic assets in the front yard of the EU, and Chinese companies are securing access to natural resources and focusing on strategic sectors such as energy, mining, and mineral processing. Beijing wants to increase its influence and deepen its economic, cultural and diplomatic presence in a region that is geo-strategically important because of its proximity with the EU, but also as a counterbalance to the region’s transatlantic relationship.[1]

A short historical background

China is not a newcomer in the Western Balkans. While diplomatic, economic and cultural ties with Beijing have existed for decades for Albania and the countries of the former Yugoslavia, activities in recent years have shown that China is laying the groundwork for a long-term, multi-faceted, and ever-deeper presence in the Western Balkans. In its narrative, Beijing aims at highlighting the shared socialist past towards the Western Balkans, using the existence of some degree of post-communist nostalgia in the Balkans, focusing on “traditional friendship” and a “shared past”.

Diplomatic relations between China and Albania officially began in 1949, and grew stronger based on the shared communist ideology. The split of Enver Hoxha’s led communist Albania with the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, opened the way for a stronger and exclusive relationship with Mao Zedong’s China. Those years were characterized by a multi-domain cooperation between the two countries, as Beijing became the key supporter of an isolated Albania, providing large loans for the heavy industry and the military industry, with big arsenals of arms and ammunitions. An important agreement was signed in 1961, where China pledged technical support to Albania for building of industrial plants and factories (chemical, food, clothing, construction materials, and steel mills). Trade volume between the two countries increased as Albania would export raw materials (oil, chrome, and copper) and mainly import industrial products and pharmaceuticals. Strong cultural links were developed during the two decades of intensive friendship, until the relationship fell apart in 1978 due to ideological disputes. Albania isolated itself further from the rest of the world until 1991, and the relationship with China never have reached that past high level.

The Sino-Yugoslav diplomatic relationship, although at good levels during the 1960s and the 1970s, became closer after the breakup between Beijing and Tirana. In 1977, Yugoslavia’s President Josip Broz Tito visited China for the first time, followed by a return visit of Chinese Prime Minister Hua Guofeng to Belgrade in 1978. Ties were strengthened in the mid-1990s, when the isolated former President, Slobodan Milosevic, found an ally in faraway China, and opened the door for the first Chinese migrants in Serbia. The alliance was further forged politically during the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, when a bomb part destroyed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese citizens inside it. Today, China is considered a strategic partner for Serbia, and the latter has become the biggest beneficiary of Chinese investments in South-Eastern Europe.

Trade between China and the Western Balkans: Higher deficits for the region

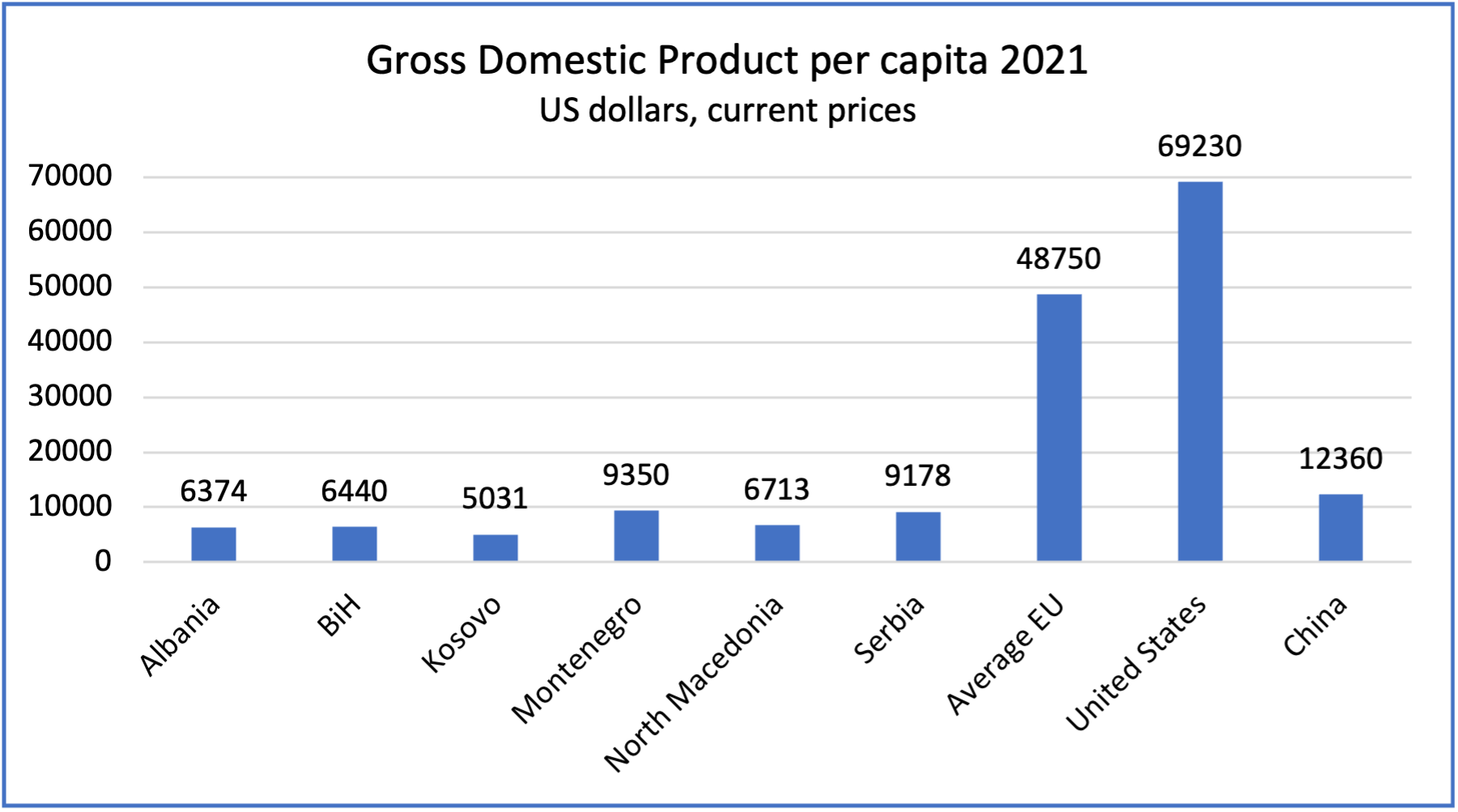

China looks at the region primarily as a market for its own exports and as a large window into Western European markets. The Western Balkans market is a small one, where all six countries represent less than 18 million consumers, with a total Gross Domestic Product of $132 billion in 2021, where Serbia makes up almost 50% of the regional market. The entire regional market represents less than 1% of the European market of $17 trillion.[2] In the last 30 years, the economies of the region have experienced high growth rates allowing some sort of convergence with the EU countries, but incomes per capita are very low compared to European standards, with only $7,200 as a regional average, representing less than 15% of the average EU incomes, in current prices (EU GDP per capita $48,750 in 2021).

As countries are falling into the “middle income trap”, the regional convergence with Europe has stalled (regional economic expansion will be 3,7% in 2022-2023), implying that it would take at least 20 years for the Western Balkans on average to double its income, and more than 50 years to catch up with the European average. The dire economic situation is a result of un-friendly business environment characterized by weak institutions and the rule of law, high levels of corruption, and the very limited role of innovation – all factors contributing significantly to the low competitiveness of the region (lowest rankings in institutions and innovation capabilities), shown by the Global Competitiveness Report.[3] Unfortunately, small and fragmented markets, coupled with a harsh business environment, cannot repay costly innovation investments, stymying any significant modernization.[4]

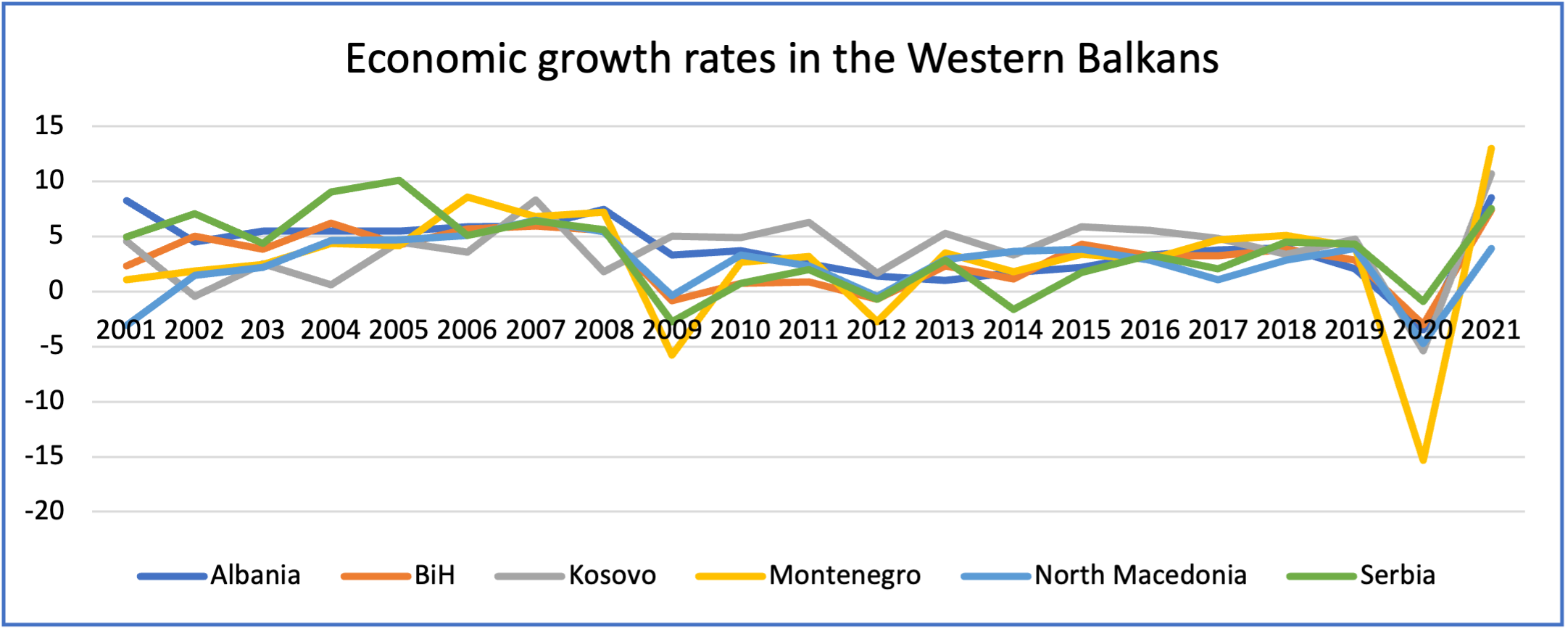

Economic convergence with the West has stalled as a result of non-sustainable economic growth rates, and a triple dip economic recession since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (Figure 1 and 2). The economies of the Western Balkans were not functioning well before the pandemic. At first sight, most countries have shown moderate growth trends in the past two decades but these are not normal balanced economies. Much of the positivity has been buoyed by a blend of remittances from its expatriate workers, citizens working within well-entrenched informal economies, and more recently, an added dimension of a growing amount of money laundering that is propping up real estate prices and artificially inflating property prices.

Source: International Monetary Fund WEO database

Source: International Monetary Fund WEO database

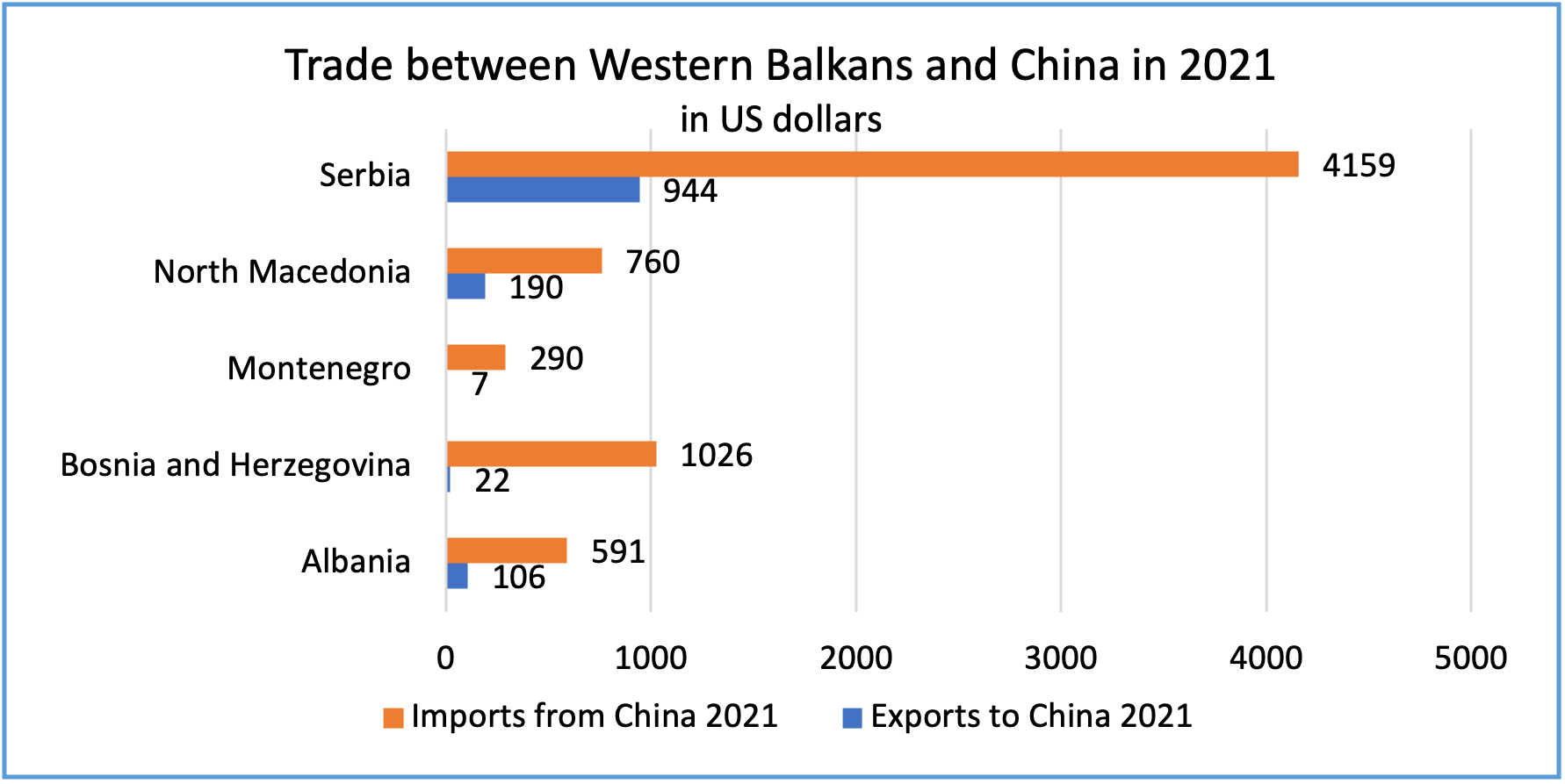

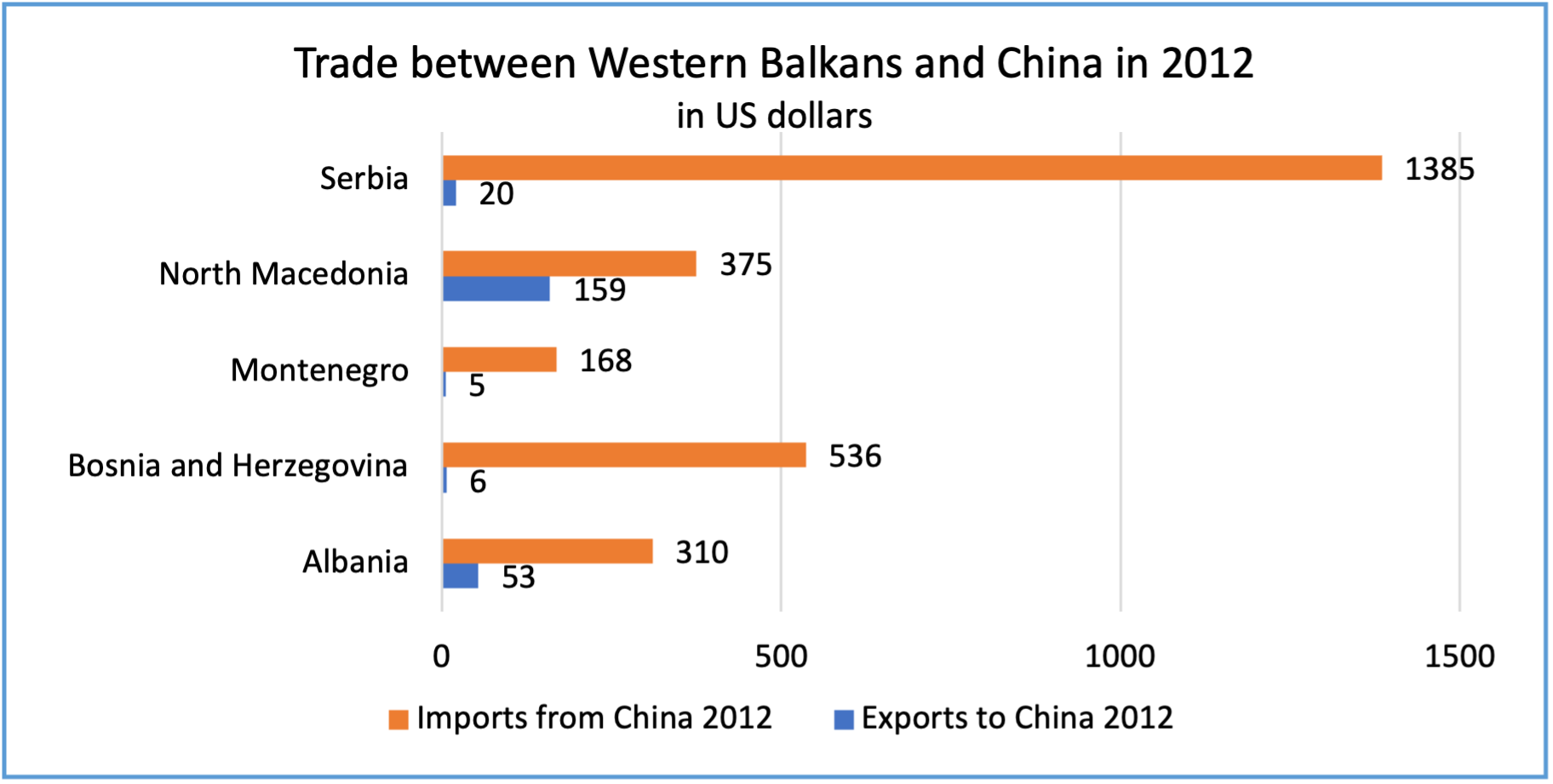

Considering the small regional market, trade exchanges with China have seen a rapid expansion, with an increase of almost three times since 2012, going from $3 billion to $ 8billion in 2021, according to UN Comtrade data (Figure 3 and 4).

Source: UNComtrade database

Source: UNComtrade database

While exports from the Western Balkans towards the Chinese market have increased over the years, the actual trade balance is very heavily tilted in favor of China (for almost 85% of trade).

This means that trade deficits towards China have risen tremendously, as regional exports into the Chinese market amounted to $1.2 billion, while imports of Chinese products in the Western Balkans reached $6.8 billion, in 2021. Nearly 60% of the trade with the Western Balkans is conducted with Serbia ($5.1 billion), China’s main strategic partner in the Balkans.

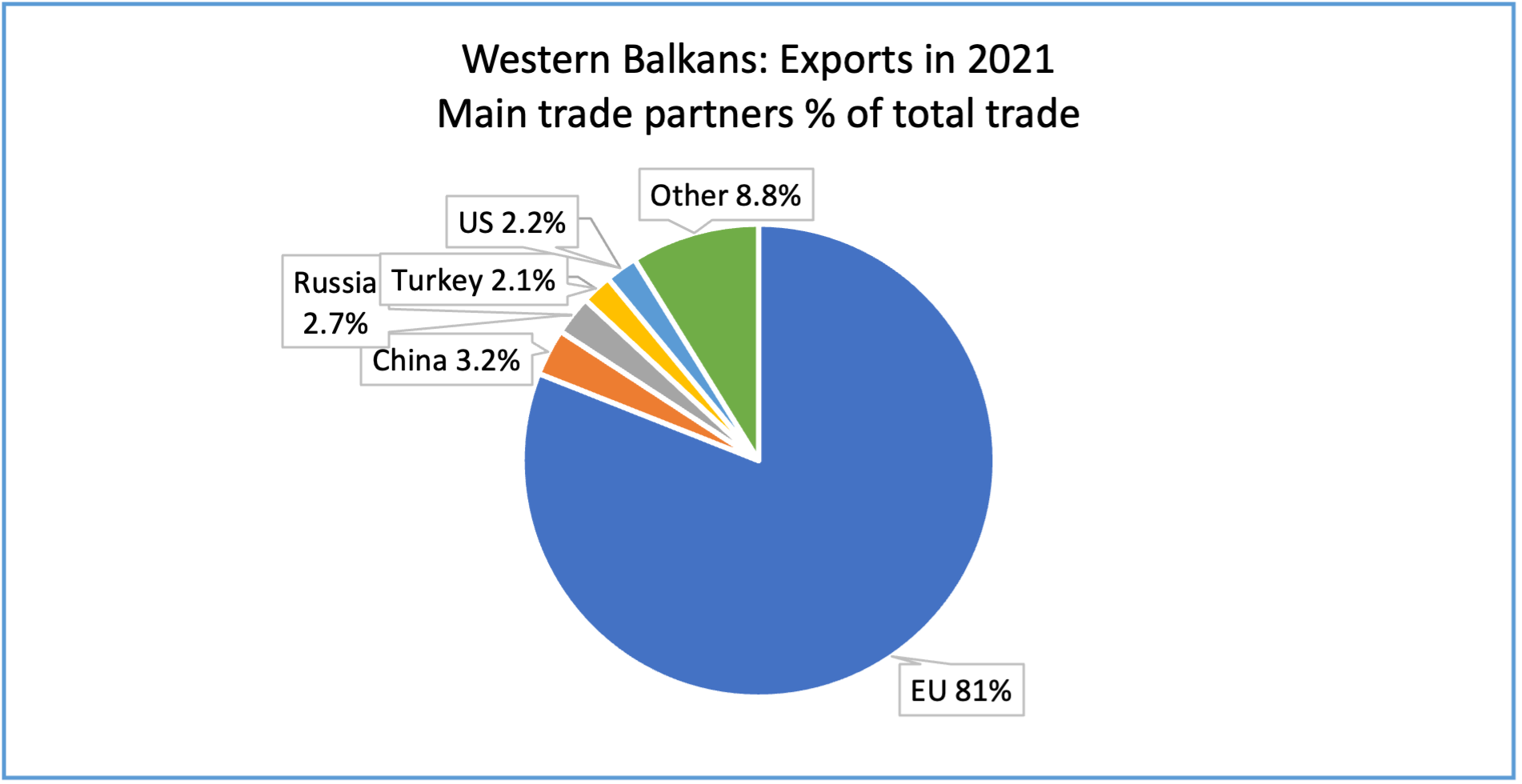

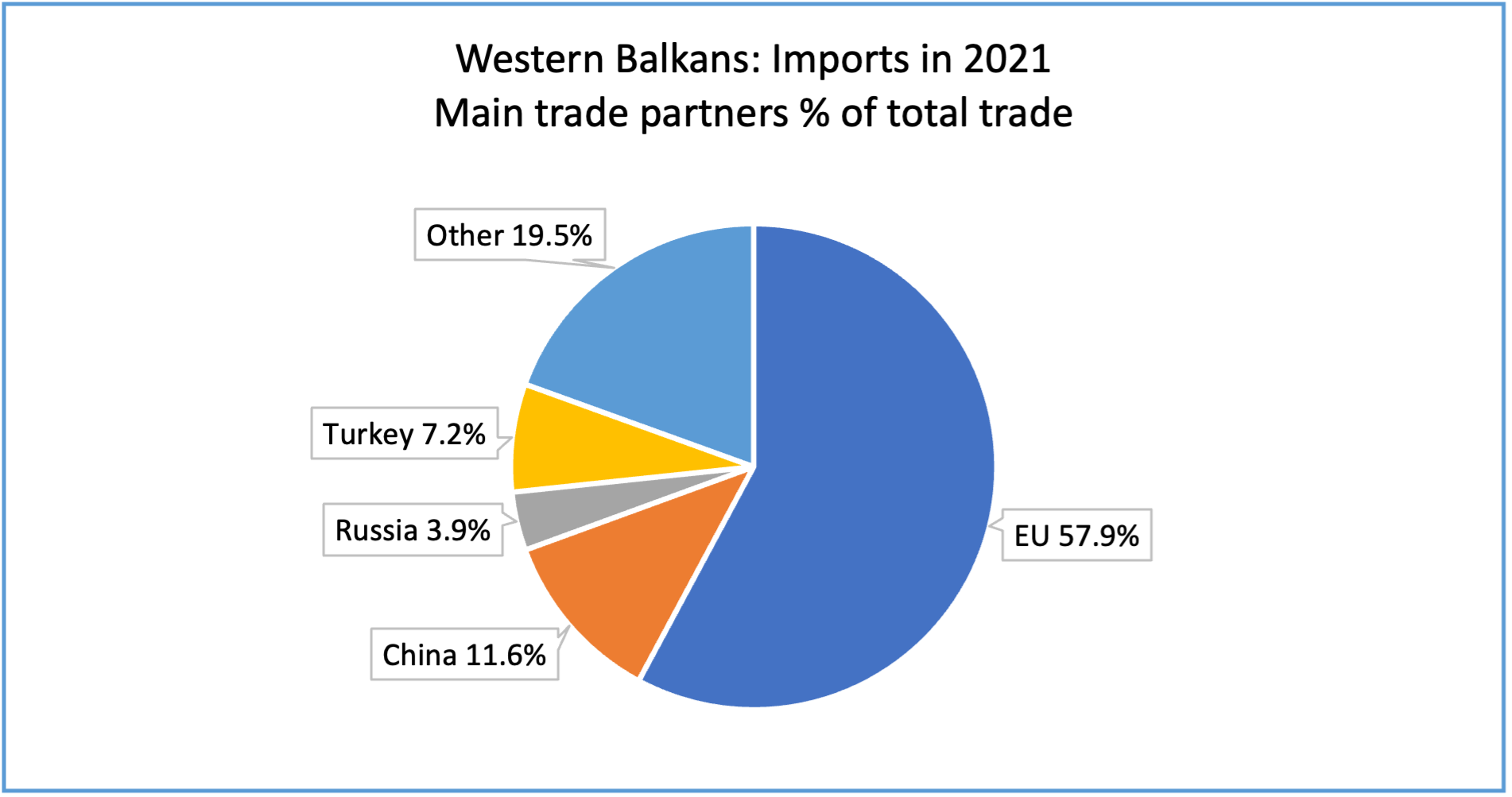

While the EU remains the main trade partner for the region with over 70% of its engagement, both for its exports (81%) and imports (58%)[5], China has quickly become the second or third largest trade partner for the region.[6] In term of European comparisons, trade with the Western Balkans makes up less than 1% of EU-China trade levels ($770 billion in 2021, according to Eurostat data[7]) (Figure 5 and 6).

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/5/5c/Western_Balkan_countries_trade_with_main_partners%2C_2021.png

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/5/5c/Western_Balkan_countries_trade_with_main_partners%2C_2021.png

Given the need for investment and the low production prices in the region, in the future we might see a trade-substituting investment strategy that could potentially allow Chinese companies to circumvent trade restrictions and export products directly to a market of 800 million people, thanks to the free trade agreements (FTA) that the Western Balkans countries enjoy with the EU.

Chinese Investment in the Western Balkans

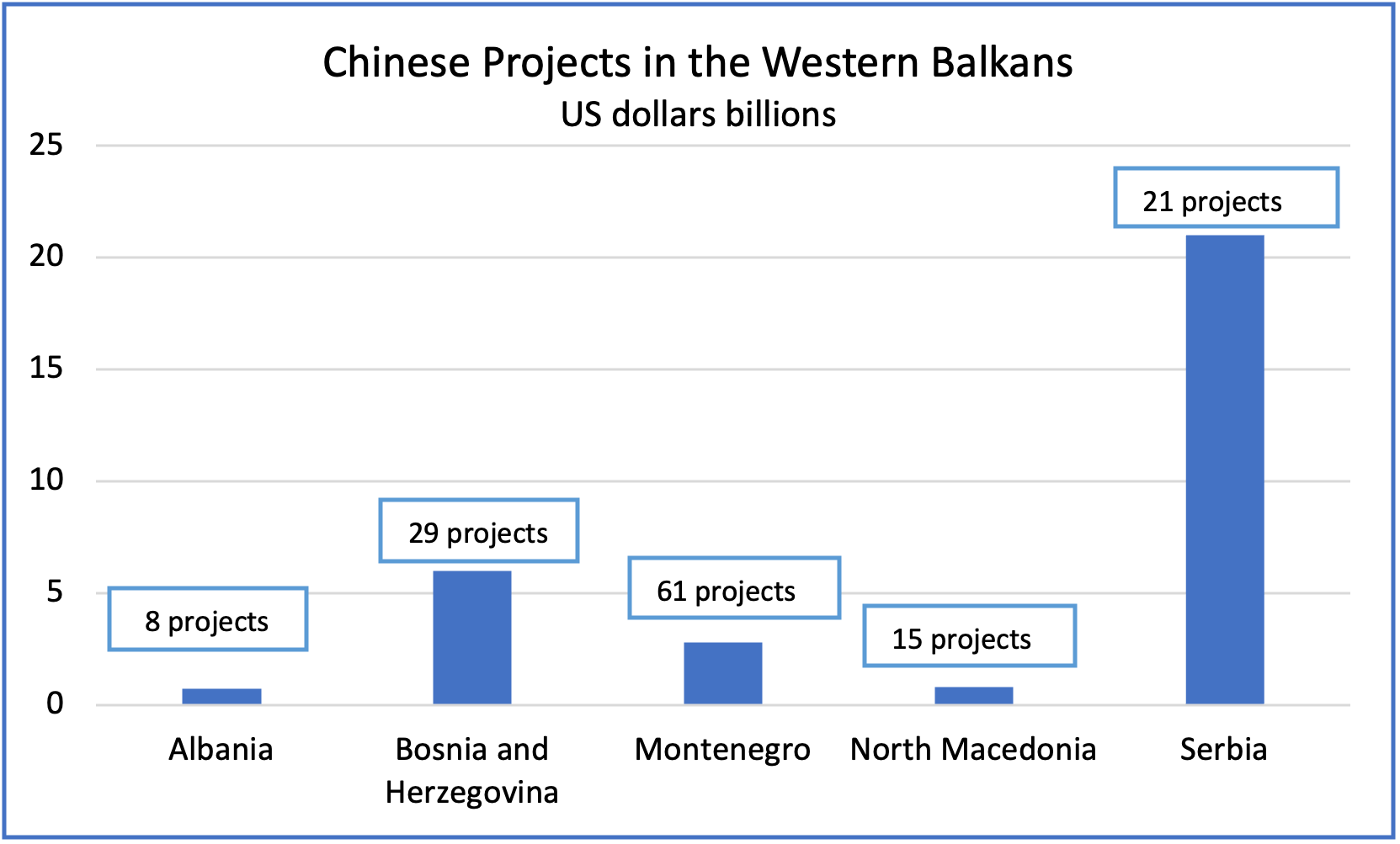

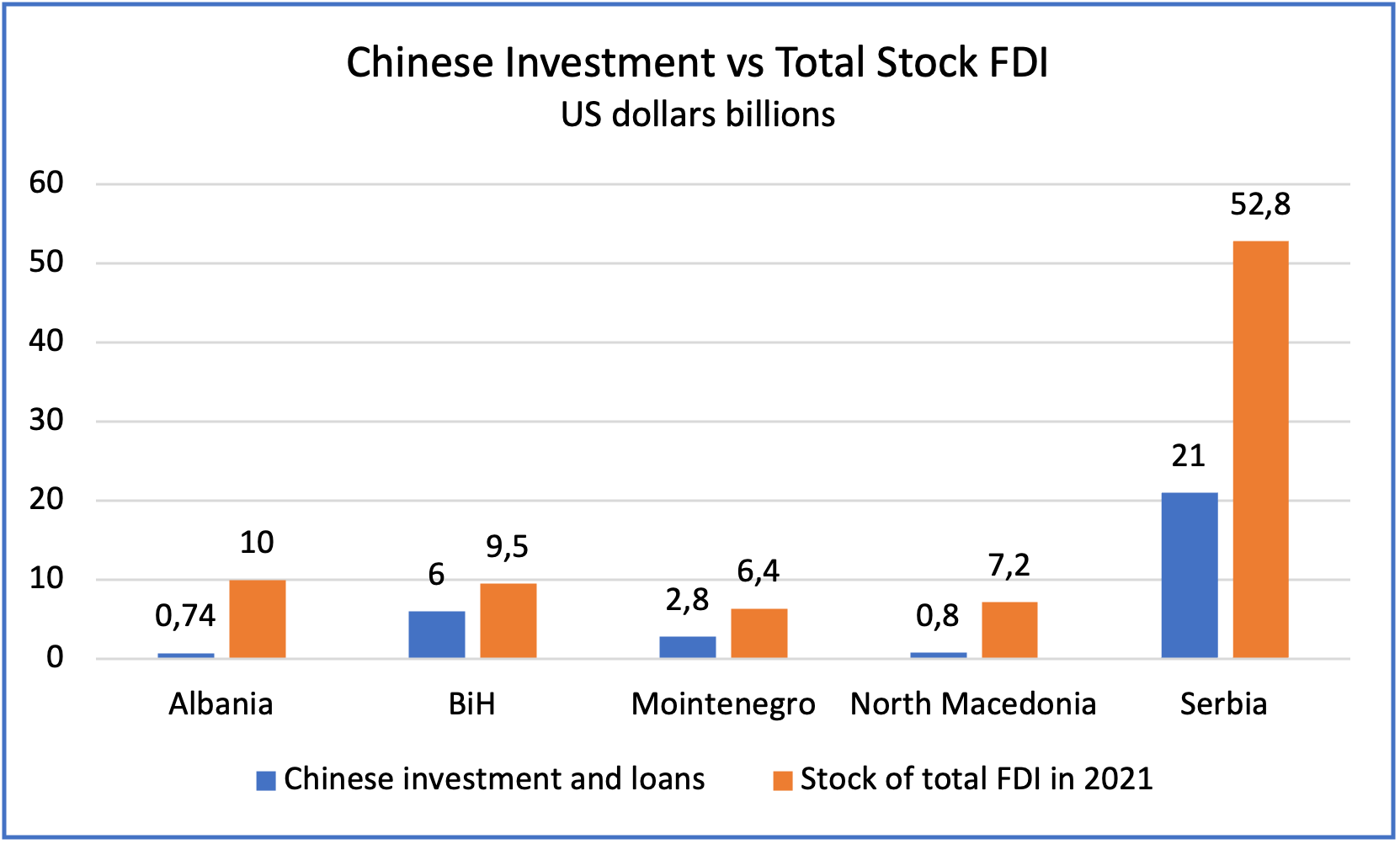

More than trade, there has been a rapid Chinese expansion in investments in the Western Balkans. According to Balkan Investigative Reporting Network data, there are currently about 122 Chinese projects with an estimated value of around $31 billion.[8] This would make up almost 40% of the total stock of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the five Western Balkan countries (excluding Kosovo), which amounted to $86 billion in 2021, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (Figure 7 and 8).

Source: BIRN Data on Chinese investments. Total projects 122 for estimated value of USD 31 billion (27.6 billion Euro)

Source: BIRN Data on Chinese investments. Total projects 122 for estimated value of USD 31 billion (27.6 billion Euro); UNTCTAD data on Foreign Direct Investment.

The entire region has attracted less than 0.2% of the global stock of FDI, despite its geo-strategic position in Europe, where the EU is one of the most important markets for the attraction of FDI with more than 25% of the stock of global FDI in 2021. On the other side, the European countries are among the main investors in the global economy, with almost 32% of the stock of outflow investment in the global economy.

A misleading aspect of the data above on Chinese investment in the Western Balkans is that most of the money is not actual FDI, but loans. In fact, the main form of Chinese economic cooperation in the region is concessional lending for infrastructure, mainly in transportation and energy, through its state-owned banks, and financial vehicles, including the Chinese Development Bank, China’s Exim Bank, the Silk Road Fund, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

The main sectors for economic cooperation are infrastructure, energy, mining and mineral processioning, and communication technology, while engagement is mainly on a government-to-government basis. Investments in the health sector, educational, and cultural centers are also present. In spite of all the activity, few projects have been concluded, most have been delayed, some have stalled, and for others, given the lack of transparency surrounding these projects, the status is unclear. Allegations of corruption, environmental pollution, and workers exploitation appear to be part of the overall fabric of these investments.

Western Balkans: A perfect testing ground

The Western Balkans has been a perfect testing ground for Chinese investment in infrastructure. China's first big infrastructure investment project in Europe was the Pupin Bridge in Serbia carried out by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), inaugurated in 2014. The first railway project in Europe by a Chinese state-owned Enterprise using funds from the EU was the 10 km segment of Kolasin-Kos railway implemented by China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) in 2017.

The same company, CRBC, wan the bidding contract to build the 2.4 km Pelješac Bridge in Croatia that connects the southern part and Dubrovnik with the mainland, which was inaugurated in July 2022. It was one of the largest EU-funded projects, with $424 million from the Cohesion Policy Funds, as the EU contribution covered 85% of the cost.[9] Called by many “ the Chinese bridge”, only the knowledgeable few knew that this was actually an EU-funded project. The awarding of the contract to a Chinese SOE has led to concerns about Chinese state funding and subsidies, and lack of transparency over the bidding process.

Chinese SOEs are able to take advantage of the lack of transparency and engage in direct contract negotiations throughout the region. Experienced in infrastructure development in other developing countries, Chinese SOEs enjoy economies of scale and can offer cheaper prices subsidized from the Chinese government interested in exporting its excess capacities and construction material they can easily outcompete western companies. The experience in the region has been important for Chinese companies also to familiarize with the EU standards, from public procurement contracts, to labour and environmental standards, and with EU practices and regulations. The difference is that China can still deploy in the Western Balkans its loan-contact model, but in the EU countries public procurements laws prohibit these practices.

As a result, the EU Council and the EU Parliament reached in June 2022 a political agreement to come up with new regulations on foreign subsidies from third countries, “Regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market”, that sought to prevent them from distorting competition for public contracts in the EU.[10]

Western Balkans’s infrastructure: A very important piece of the BRI puzzle

China is attracted to the Western Balkans for its geo-strategic location and the proximity to the EU markets. In line with its BRI objectives, Beijing is heavily investing in large-scale infrastructure projects and taking advantage of the urgent needs for infrastructure in the Western Balkans.

Beijing is developing the 21st Century Silk Maritime Road or the China-Europe Land-Sea Express Route (LSER) as one China-EU trade corridors of the future, an important component of the BRI that links China with Western Europe via the entry port of Piraeus in Greece and the infrastructure networks in the Balkans, through North Macedonia and Serbia into Hungary. The Chinese state-owned China Overseas Shipping Group Cp. (COSCO) has a controlling majority (67%) of the Port of Piraeus[11], and it has become the main entry point for Chinese goods in Europe, shortening normal shipping times by one week. Chinese goods travel by sea into Piraeus, and are transported by train through Serbia and North Macedonia into Hungary and the Czech Republic. In 2019, COSCO also bought a 60% majority stake of the Greek railway company Piraeus Europe - Asia Railway Logistics (PEARL) and a minority stake in the Budapest train terminal in Hungary. Chinese SOEs have also a minority stake in the Port of Thessaloniki in Greece.

China’s long-term strategy in the Balkans views Serbia as a strategic European transportation hub. With 61 projects valued at more than $21 billion, the most significant is the upgrade of the Belgrade-Budapest railway. In the Western Balkans, one of the biggest projects is the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway, agreed in the “16+1” Summit in Riga in 2016, to be financed 85% by China Exim Bank (USD 2.5 billion) and implemented by China Railway and Construction Corporation. For two sections of the Belgrade-Budapest highway, Serbia has already borrowed $1.5 billion. Another important Chinese transportation project in Serbia includes the modernization of the 204 km railway line between Belgrade and Nis, as part of the European Corridor X that connects Salzburg in Austria with the port of Thessaloniki in Greece. The project is estimated to cost more than 2 billion euros, and is discussed to be implemented by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC). The only completed infrastructure project in Serbia is the Pupin Bridge, China's first big infrastructure investment in Europe as opened by PRC Premier, Li Keqiang, and Serbian President, Aleksandar Vucic, in December 2014, implemented by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC).

North Macedonia is also an important country in the BRI framework. In 2013, the Government of North Macedonia borrowed more than $800 million from China’s Exim Bank for the construction of two highways. The Miladinovci- Shtip was completed in August 2020, and the Kichevo- Ohrid highway (an integral part of European Corridor VIII) is yet to be completed, while construction costs have increased and could rise to $1.2 billion (if interest payments are included), implemented Sinohydro Corporation. Both projects have been overshadowed with corruption allegations.

In Montenegro, the Bar-Boljare highway is the biggest Chinese project linking the port of Bar in the Adriatic Sea with Serbia, financed by China’s Exim Bank for almost $1 billion (only for the first section of the highway, making it one of the most expensive highways per km in the world with $20 million per km), and being built by the China Road and Bridge Corporation (RBC). This financially unsustainable project signals the Chinese interest in the port of Bar. With only 41 out of 165 km completed, “the road to nowhere” had raised questions about the financial feasibility of the project and the unsustainable debt associated with it, sending Montenegro’s sovereign debt rocketing to 103% of economic output. According to estimates of the Montenegrin government, the remainder of the highway will cost an additional USD 2 billion.

Chinese companies have also been involved in upgrading the railway network in Montenegro. China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) completed in 2017 the reconstruction of a 10-km segment of the Kolasin-Kos railway for $8 million. For Beijing, it was a very important project as it represented the first railway project in Europe by a Chinese company with funds from the EU.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chinese construction companies are involved in the construction of the 12-kilometre-long Počitelj–Zvirovići section of a highway at a cost of $75 million (EUR 66 million), financed by the European Investment Bank.

In Albania, China Everbright, a Chinese state-backed company bought all the shares to run Tirana International Airport from AviAlliance GmbH (A German-American investment) for $90 million, the then sole airport in the country[12]. This was China’s major investment in airport infrastructure in a NATO country. Only four years after under unclear circumstances, the Chinese company sold the concession fully to a local one for a transaction that was valued about $80 million (EUR 71 million).[13]

Investment in infrastructure is a public good that could foster sustainable economic development, but the positive developmental spillovers depend on the practical details of implementing these projects, and the institutional absorptive capacities of the host countries. Considering the huge infrastructure deficits in the Western Balkans, Chinese state backed enterprises can easily outcompete western companies with their opaque way of doing business with established political elites, enabled by high levels of corruption in the Western Balkans, taking advantage of existing problems of a lack of transparency in the region. Chinese SOEs engaging in infrastructure have acquired experience in other developing countries and have advantages of scale offering cheaper prices as a direct result of state support interested in exporting its excess industrial capacities construction, steel, and cement.

Chinese interests in Energy and Mining

Another important pillar of China’s expansion policy concerns securing its present and future demands for commodities, mainly by investing in countries rich in natural resources such as steel, cooper, and oil. The Balkan energy sector is also very attractive for Chinese SOEs, as major western utility companies are unwilling to make risky investments. Albania, Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina are attractive for their hydropower capacities while North Macedonia and Serbia and Croatia for their wind energy potentials. Chinese investments in these areas are mainly focused on acquisitions and privatization.

In 2016, China’ state owned Hesteel Group took over Smederevo’s steel mill for $55 million, a former US investment that was sold back to the Serbian government in 2012 for a symbolic value of 1 dollar. The company pledged to keep on the 5000 workers, and President Xi Jinping. HBIS Group Serbia has become Serbia’s biggest exporter company. Another important investment in Serbia’s mining industry is Zijn Mining Group that holds the controlling majority in RTB Bor copper factory, for an estimated investment of more than USD 1 billion, including plans of expansion. Shandong Linglong is the main company involved in major green field FDI in the region, with a tire factory in Zrenjanin, an investment of around $900 million.

China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) is building a third, 350 MW unit at thermal coal power plant of Kostolac (east of Belgrade) with a $600 million Exim Bank loan, as well as the expansion Drmno open cast lignite mine in the Kostolac basin. As Serbia meets 70% of its electricity with lignite, concerns have been raised that Chinese investment in coal plants and mines are delaying the coal-out phase and hindering Serbia’s progress away from fossil fuels, while undermining its pledge to combat climate change as these investments are breaching the EU environmental laws in the region. Concerns related to environmental pollution have sparked protests, despite the fact that these are significant investments for the Serbian economy and have contributed to the rise of local employment.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chinese interests have focused on two big energy projects, the Stanari coal power plant (in 2013 for $400 million financed by China Development Bank) and the Tuzla lignite power plant (in 2017 with a first loan of $800 million from Exim Bank and implemented by China Gezhouba Group, part of China Energy Engineering Corporation), accumulating for the small country a debt of more than $1.2 billion (13% of BIH’s external debt) and becoming an iconic example of the clash between Chinese investments and EU environmental standards [14]In fact, four years after the approval of a public guarantee for the Tuzla 7 lignite plan, the State Aid Council of Bosnia and Hercegovina revoked the approval of the loan, a decision that settles an infringement procedure launched by the Energy Community Secretariat in 2019, considering the “negative impact on the interest of all citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina as air pollution is responsible for severe health and environmental damages”[15] Preliminary contracts have been signed on other multiple thermal plants, but few have been implemented, such Ugljevik III was reportedly financed with a $782 million loan from China Development Bank (CDB), but it has not been executed.

In 2020, the government of the Republika Srpska (one of the two political entities that make up BiH) signed an agreement with China Gezhouba Group for a USD 216 million investment to [C1] to build the Dabar hydropower plant in the country’s south. Another investment from China Electric and Polish-Chinese firm Sunningwell International has been announced for the construction of the Ugljevik 3 thermal power plant[16].

In Albania, the Chinese Geo-Jade Petroleum, a Chinese private enterprise that entered in the oil business in 2013, owns the concession to extract oil in Patos-Marinza oil field (since 2016), the biggest field in the country producing 95% of Albania’s crude oil and accounting for 11% of its exports.[17] This is also one of the largest onshore oil fields in continental Europe. The company also owns Kucova and Block F fields. The concession price was around $442 million but it was bought from Bankers Petroleum, a Canadian company. As a result, this does not appear in data as a Chinese FDI in Albania, and the name of the company was not changed by the Chinese owners, going under the radar. According to Bankers Petroleum, this is the largest foreign investor, largest taxpayer and one of the largest employers in Albania, but recently the company has run into environmental problems and was fined from Albanian state authorities.[18]

Another Chinese investment in the Albanian mining sector relates to copper, as in 2014 Jiangxi Copper Corporation, the largest copper producer, manufacturing and distributing copper products in China) bought 50% of the stakes (for a price of $65 million) of a Turkish mining company operating in Albania, owned by Turkish “Ekin Maden”, operating in Albania in Albania in a partnership with Beralb Sh.A.S[C2] ”[19]. The Turkish-Chinese joint venture is the leading company for the exploration and processing of copper and has a concession until 2043 for several copper mines and plants in Albania.

Security and Technology

One of the main countermeasures against China’s influence activities has taken place in the areas of security and technology. The impact is evident in China’s recent failure to make headway in its efforts to gain a foothold along the Adriatic coast, in Albania and Montenegro, and in 5G networks in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Albania. After the United States Department of State highlighted the risks of Huawei in 5G networks, and led “The Clean Network”, a bipartisan effort to address "the long-term threat to data privacy, security, human rights and principled collaboration posed to the free world from authoritarian malign actors".

With the exception of Serbia, all countries of the Western Balkans are signatories of The Clean Network, although Huawei has a large presence in the region, thanks to China's close cooperation with Serbia. Although Serbia is not formally a part of the "Clean Network", Serbian authorities did sign an economic cooperation agreement with Washington, in which they committed to prohibit the use of 5G equipment from "untrusted vendors". However, in this particular agreement there was no direct mention of either China or vendors like Huawei.

Serbia the strategic partner in the region

Chinese interests in Serbia are noteworthy. With the largest economy in the Western Balkans, Serbia has become Beijing’s go to partner in and a clear frontrunner in the framework of the 16+1. China and Serbia upgraded their relationship to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” in 2016, the same year they signed a mutual visa-exemption agreement.

Relations between Belgrade and Beijing extend beyond economic ones, as Serbia has also signed a USD 3 billion package of economic support and military purchases that has boosted the Chinese influence in the country. Another important project is the Huawei-led installation of smart surveillance cameras with advanced facial and license plates as a measure to fight crime, raising concerns on the compatibility with EU standards on privacy and data protection, as enshrined in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). A successful US-led initiative in the area of security and technology was the inclusion of Western Balkans countries (except Serbia) in “The Clean Network” countering Huawei’s efforts to gain a foothold in 5G networks along the Adriatic coast.

The special bond between the two countries was further strengthened during the COVID-19 crisis, where the Chinese vaccine gave an important boost to the government of Serbia as it struggled to deal with the pandemic.

China’s Soft Power in the Western Balkans

China is becoming one of the most prominent actors in the Western Balkans. Beijing is cultivating an image of itself as a benign global power, and presents itself as a credible source of economic development and a reliable partner looking for opportunities to invest in strategically important sectors.

The key driver behind China’s clout in the region is its promotion of its development model utilizing “its” capital as an “economic miracle-maker,” and by raising expectations about Beijing’s ability to bring wealth to the Western Balkans, using its economic carrots and levers for public relations and strategic messaging to influence public opinion. Beijing is taking an opportunistic approach in the region, combining elements of infrastructure project investment that we see in developing countries, and developing economic ties with EU countries, such as in the framework of the 16+1. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) started engaging with the countries bilaterally in the early 2000s, moved to a regional approach after the launch of 16+1, and eventually moving to a hybrid approach that varies based on country specificities.

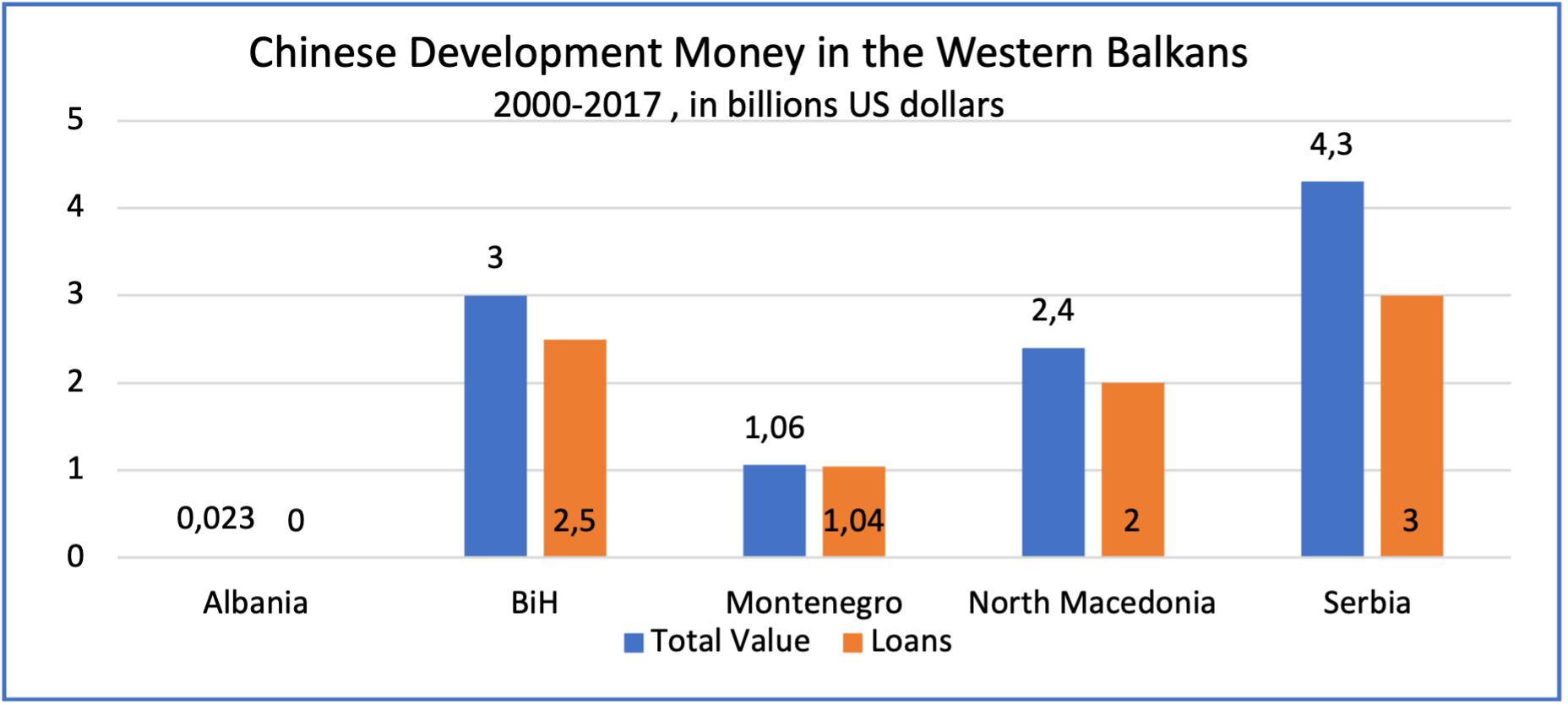

Beijing seeks closer relations with the Western Balkan countries, operating mainly in bilateral basis, but using similar policies and tactics throughout the region. While Chinese development money is not transparent, the AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, records 197 development projects supported by official financial and in-kind commitments from China from 2000-2017[20] with a total of value of USD 10 billion, including more than USD 8.5 billion of concessional lending. About $1.5 billion are spent in development aid in projects that range from grants to support for the public administration, donations for agriculture modernizations, schools, Confucius Institutes through Hanban funds, debt forgiveness, trainings, but also police and military cooperation, mainly in Bosnia and Hercegovina and Serbia. (Figure 9)

Source:https://www.aiddata.org/data/aiddatas-global-chinese-development-finance-dataset-version-2-0

In its narrative, Beijing aims at highlighting the shared socialist past towards the Western Balkans, using the existence of some degree of post-communist nostalgia in the Balkans[21], focusing on “traditional friendship” and “shared past”. Beijing’s official rhetoric emphasizes equality and mutually beneficial economic interaction, directing attention away from values and politics, but the long-term objectives are strategic, political, and increasingly ideological.

The overwhelming majority of China-Western Balkans cooperation involves state institutions and is based on a system of shared interests focused on: legacy contacts and relationships from the times of the Cold War; institutional partnerships and alliances across state structures; and a new growing network of actors from the civil society, academia and the media.[22] Beijing’s soft power efforts are mostly directed at certain key influential elites in business, politics, academia, or NGOs.[23] Any investment in the Western Balkans is low hanging fruit for Beijing compared to other European countries.

With the aim of building a community of friendly countries, Beijing is heavily investing in cultural diplomacy, from the Confucius Institutes present in every capital of the region, to chambers of commerce, and cultural centers. Confucius Institutes are a key tool of China’s cultural diplomacy, tasked with promoting a positive worldwide image for Beijing and as part of the strategy to construct an efficient communications infrastructure through government-run institutions that offer language and cultural programs[24], while spreading propaganda and interfering with free speech on campuses.[25] In this respect, the United States Senate has passed by unanimous consent a bill that would increase oversight on Confucius Institutes, and other China-funded cultural centers that operate on U.S. university campuses, and would cut federal funds to universities and colleges that have Confucius Institutes that don’t comply with new oversight rules and regulations.[26] Similarly, in the EU several Confucius Institutes chapters have recently been shut down.[27]

Beijing has established Confucius Institutes throughout the Western Balkans[28], with the first institute in the region opened in Belgrade in 2006 and the rest after the establishment of the BRI: Two in Serbia at state universities of Belgrade (2006) and Novi Sad (2014)[29], at the University of Tirana in Albania[30] (2013), at Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje[31] in North Macedonia (2013), at the University of Sarajevo[32] (2015) and at University of Banja Luka[33] (2018) in BiH and at the University of Montenegro[34] in Podgorica (2017)).

In addition, Beijing promotes the creation of “Confucius Classrooms” at primary and secondary schools[35]. The Government of Serbia has started a pilot project for the introduction of the Chinese language into 31 primary and secondary schools in the country, a project that started in 2012 involving more than 2500 students. More than 700 students are involved in similar courses in Montenegro, with similar numbers in Republika Srpska. In Albania, Confucius classrooms were set up in several high schools in Tirana since 2013.[36] Establishment of Chinese Cultural Centers continues to gain ground across the region, mainly in Skopje, Belgrade, and Tirana.[37]

Academic links between China and the Western Balkans countries are growing, typified by the increasing range and intensity of interaction between national academies of sciences.[38] This involves China’s cooperation agreements with local institutions; the creation of new academic programmes; regular exchanges of personnel; joint research projects; the commissioning of analyses on areas such as economics and politics at the individual and institutional levels; the establishment of new teaching positions; and other initiatives.

Scholarships have also been one of Beijing’s public policy tools, offering them on a bilateral basis, with Serbia receiving the highest number. Informal interactions between China and Western Balkans countries have grown through tourists, facilitated by the visa relaxations and abolitions in Serbia[39] (2017) and Albania[40] (2018).

Governmental and party cooperation with China occurs at the bilateral and multilateral levels (China-CEEC Young Political Leaders’ Forum[41]), as seen in BiH, Montenegro, Serbia, and North Macedonia. China also takes part in the World Political Parties’ Dialogue, as part of the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to complement interstate cooperation with that based on ideological affinity.

The establishment of Friendship Associations in all five countries describes the bilateral engagement of China with Western Balkans countries. Other forms are twinning agreements, such as in Serbia, Belgrade and Novi Sad and sister cities of Beijing and Changchun, Beijing-Tirana and Lanzhou-Fier in Albania, Skopje-Nanchang in North Macedonia, and Sarajevo-Tianjin in Bosnia and Hercegovina.

In recent years, there has been a marked rise in China’s media presence across the Western Balkans. China is paying greater attention to culture in the media content it generates and promotes in the region. One of the core objectives of the CCP’s media management strategy is to get the international media to promote China’s political language and talking points. The objective is to gain a broader public profile to promote the Chinese economic and political model, and shape positive narratives about China, avoiding negative news stories. News stories consist of information that is neutral in tone, and orientated towards economic issues, but they generally lack critical evaluations of China’s activities. These outlets often appear to avoid references to information about questionable conditions attached to Chinese projects in the region, or human rights issues in China. Chinese diplomats are increasing their presence in Western Balkans social media networks, with ambassadors setting up Facebook and Twitter accounts to disseminate official messages, and publishing op-eds in the local media promoting China’s foreign policy perspective.

Chinese state cooperation with local journalists is now a well-established mechanism of interaction, one that particularly focuses on pro-Beijing reporters and authors, describing them as “missionaries”[42]. The CCP is trying to promote a new generation of “Friends of China” with offers of generous scholarships and trips to China. Following study visits to China, such journalists routinely receive approaches from the Chinese authorities to write positive stories about their experiences, and participating in various media projects sponsored by Beijing.

A study conducted in Albania in 2020 counted more than 1000 China-related articles over a five-year period, where 47% were positive, 38% slightly negative, and 15% were neutral.[43] In BiH, the CCP is promoting a positive image, building cultural and economic influence, with efforts more pronounced in Republika Srpska. The Belt and Road think tank owns two media outlets (China Today and Voice of China), and the Federal News Agency has a cooperation agreement with Xinhua.[44] In Montenegro, media coverage is mostly positive, highlighting China’s economic, scientific, and technological successes, relying mainly on Chinese sources for news or media sources from Serbia. Media is promoting a controlled narrative when even the CCP is portrayed in a very positive light, as a benevolent global power.[45] In North Macedonia, local traditional and social media are the main channels of communication of the Chinese narratives, where the Chinese Ambassador in Skopje is also very active,[46] emphasizing Chinese positive role in North Macedonia during the pandemic. The lack of public debate and the critical approach on China’s sponsored content, combined with low media literacy enhances the vulnerability of the country to Chinese influence.

On the other side, Beijing has supported Republika Srpska in the international arena, abstaining in 2015 from a United Nations Security Council resolution condemning the genocide of Bosniak Muslims at Sebrenica in 1995.[47] Beijing activity is rising as, in collaboration with Russia, they are stepping up pressure on Western partners in the escalating crisis over BiH. While the EU and the USA are trying to convince Bosnian Serbs to end the blockade of government authorities, Moscow and Beijing are seeking an early end to the international administration, vested with special powers. They have announced non-recognition of the new international administrator in BiH. However, their attempt to get the UN Security Council to roll back the international administration in BiH failed in summer 2021 because their joint resolution was not supported.[48] In return, President Milorad Dodik has openly expressed support for China in terms of maintaining peace and stability in Hong Kong.[49]

Public perceptions of China in the Western Balkans

Political behaviour shapes public perception in the former socialist countries of the Western Balkans. Few in the region have an opinion on the domestic situation in China, and the geographical distance plays in Beijing’s favour. Chinese suppression of Uygur Muslims is not a media topic, and in general the topics of Hong Kong or Taiwan are treated neutrally, and in many cases using Chinese sources. The presence of a weak civil society and the oligarchic influence over media in the Western [C3] [VZ4] Balkans provide opportunities for China to step in and fill the void.

Generally, the political elites see the presence of China as purely economic and beneficial, and mostly opportunistic. The short-term impact of the Chinese foothold is considered without any strategic analysis about the long-term implications, either economic or political. Too often governments in the region lack realistic strategies needed to guide economic planning and are unable to enlighten public opinion towards any desired economic end-state.

Chinese projects are easily aligned with political cycles and coupled with top-down, rather than transparent and market-driven procurement decisions. Beijing’s offers allow decision-makers in the region to fuel patronage networks and boost short term electoral advantages. However, promises of increased economic support for Western Balkans states have not yet materialized, and China is slowly acquiring the reputation of a ‘lending power’ with uncertain and increasingly dubious overall economic intentions.

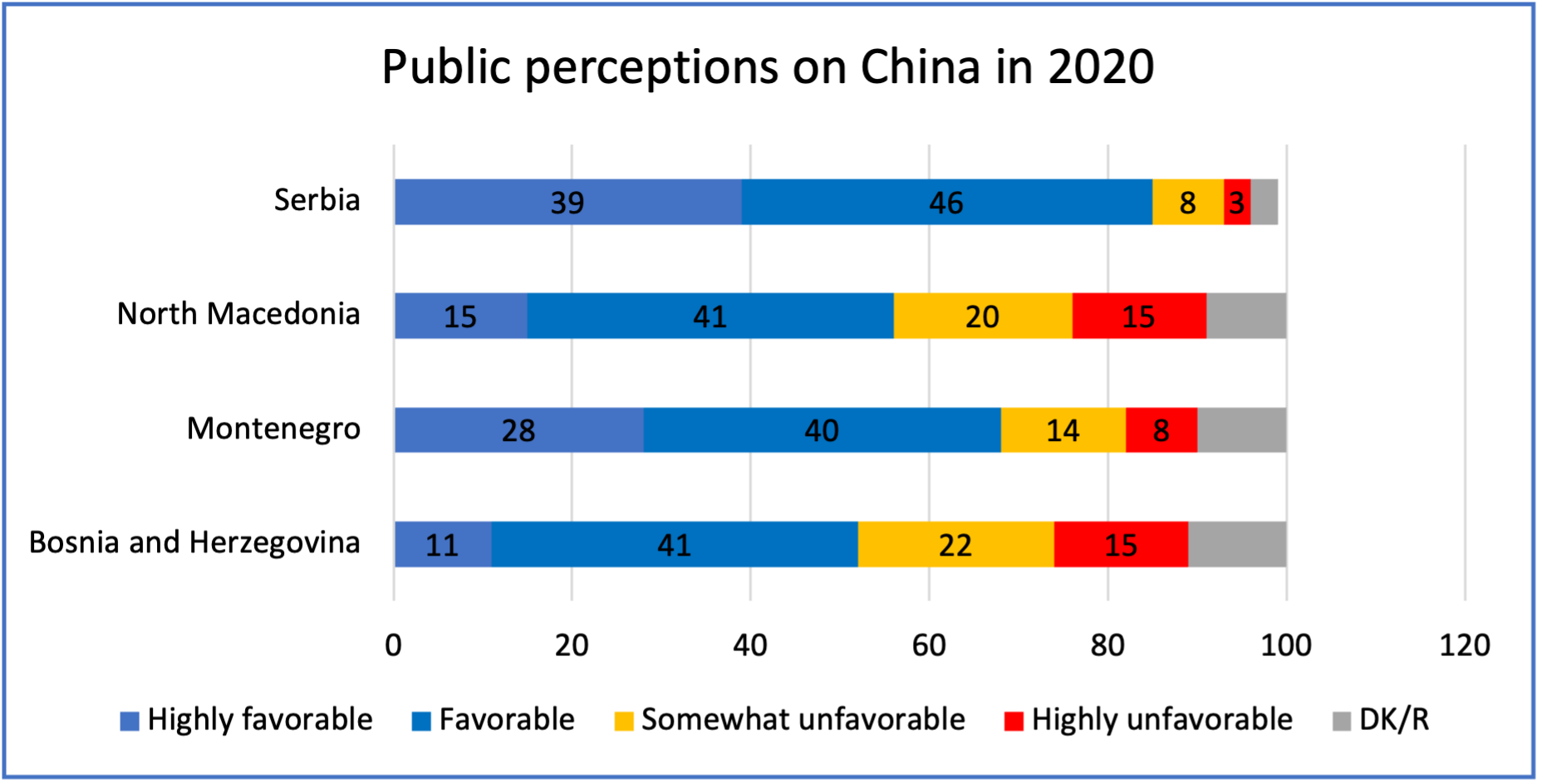

China’s popularity in the Western Balkans is increasing and is not viewed as a counter option to the Euro-Atlantic aspirations of the region. The 16+1 platform is not well known, or understood, and the impact of the BRI is not seen as significant. Local institutions and actors in are positively disposed and keen to develop and deepen bilateral relations with China. According to polls conducted by the International Republican Institute in 2020, the majority of people in the region view China favourably, from 85% of people in Serbia (among which 39% very favourable), to 68% in Montenegro, to 56% in North Macedonia, and 52% in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In a simple correlation analysis, higher is the Chinese economic engagement in the region, more positive the public perception on China. (Figure 10)

Source: https://www.iri.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/final_wb_poll_for_publishing_6.9.2020.pdf

COVID-19 and Chinese aggressive diplomacy

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the Western Balkans became a stage for China’s mask diplomacy. This strategy, involved showering target countries with medical supplies, allowing China to depict itself as a generous donor while, at the same time, trying to clear its name from the accusation of having mishandled data in the first phase of the outbreak. The COVID-19 pandemic and the response in the western countries was seen as an opportunity to delegitimize liberal democracies around the world.

The Mask diplomacy was successful in the region, presenting China as a legitimate partner or even a saviour, as depicted in the images of the Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić kissing the Chinese flag. When mask diplomacy turned into vaccine diplomacy, Serbia remained the epicentre of China’s strategy. In fact, the Serbian case is quite peculiar, as it replicates the Chinese vaccine diplomacy model on a regional scale.[50] Chinese support for Serbia was promoted also in Montenegro in describing China as the “saviour” and highlighting the indifference of the western European countries. Serbia took the chance to play the lion’s share and gave doses to other countries in the region.

In the Western Balkans, disinformation about the origins of the virus, and conspiracy theories surrounding the pandemic and the pharmaceutical industry have been amplified with the official start of vaccination campaigns, where social media was used as an important channel of communication to spread these narratives. Chinese media and officials have widely promoted the supply and planned production of Chinese vaccines in Serbia, which reflects the country’s important role in promoting China’s vaccine diplomacy and overall positive image in the Western Balkans.[51]

The so-called “vaccine diplomacy[52]” used by China (and Russia) followed a zero-sum game logic, used to strengthen their geopolitical roles in the Western Balkans to the detriment of Western powers, combined with disinformation and manipulation efforts to undermine trust in Western-made vaccines, EU institutions and Western/European vaccination strategies. The campaigns were focused at undermining the EU’s credibility as it failed to extend its solidarity to neighbouring countries at the beginning. The EU External Action Service report links the deliveries to disinformation campaigns aimed at shifting attention from China’s role in the outbreak and reducing the credibility of the West’s handling of the crisis.[53] In reality, the EU Commission delivered an assistance package of $450 million (EUR 410 million) for the Western Balkans, with $45 million (EUR 38 million) for immediate aid to the region’s health systems for purchase of medical equipment, protective gear, and other needs, and the rest to support reforms in the health sector.

How is Chinese influence affecting the EU integration of the region?

Beijing publicly supports the EU integration of the region and is not openly using tools to export its communist ideology in the Western Balkans, but with its large infrastructure projects based on the state-led model negative spillover effects could increase the risk of undermining the EU’s reformist agenda in the region. Overall, market stability seems to be Beijing’s preferred position for the time being.

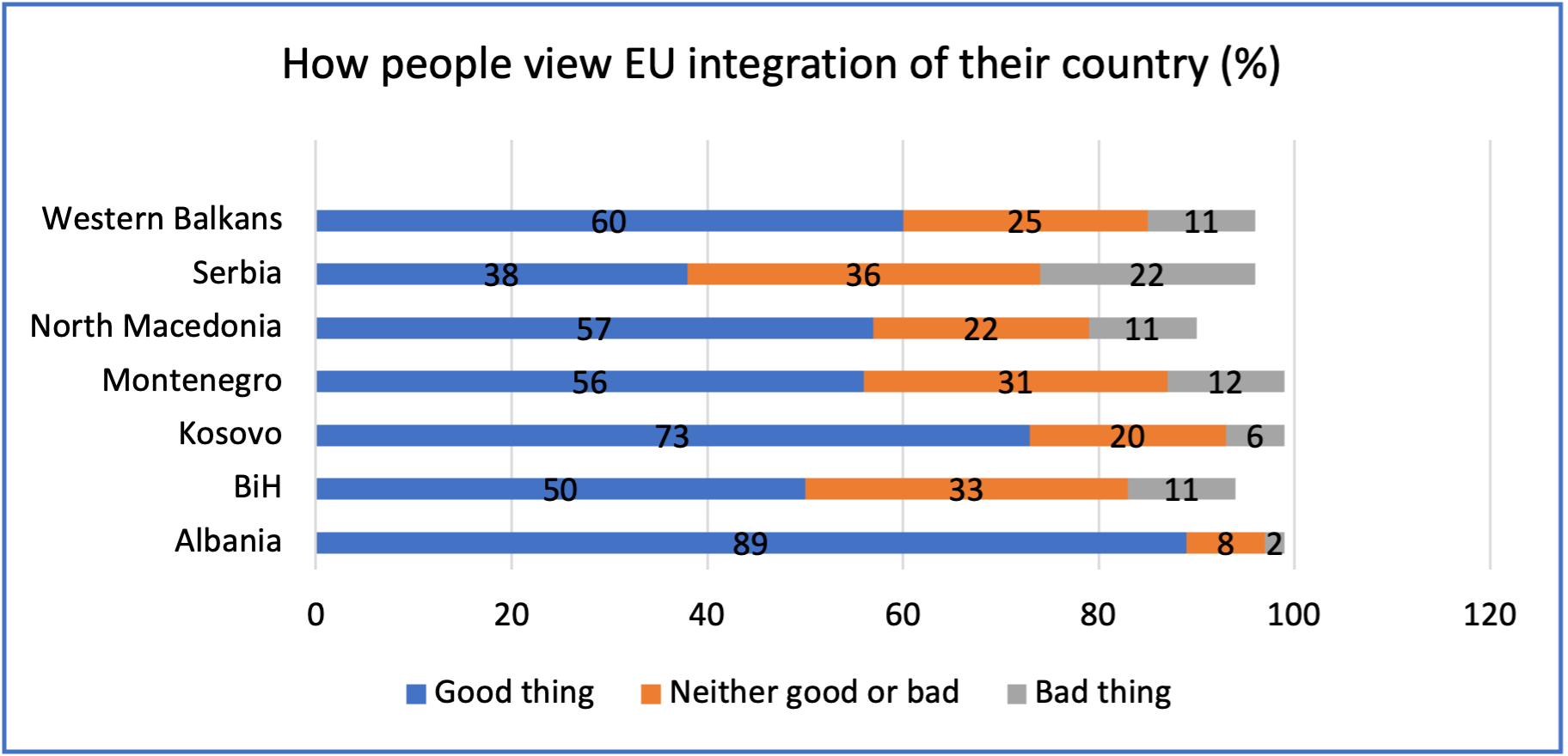

Citizens of the Western Balkans countries are still, overall, positive about the prospects of their countries joining the EU, however the integration process is burdened with EU uncertainties, a long-lasting “enlargement fatigue” that has further spilled over a “reform fatigue” in the Western Balkans, the global pandemic crisis, and the questionable dedication of some of the political elites within the region.

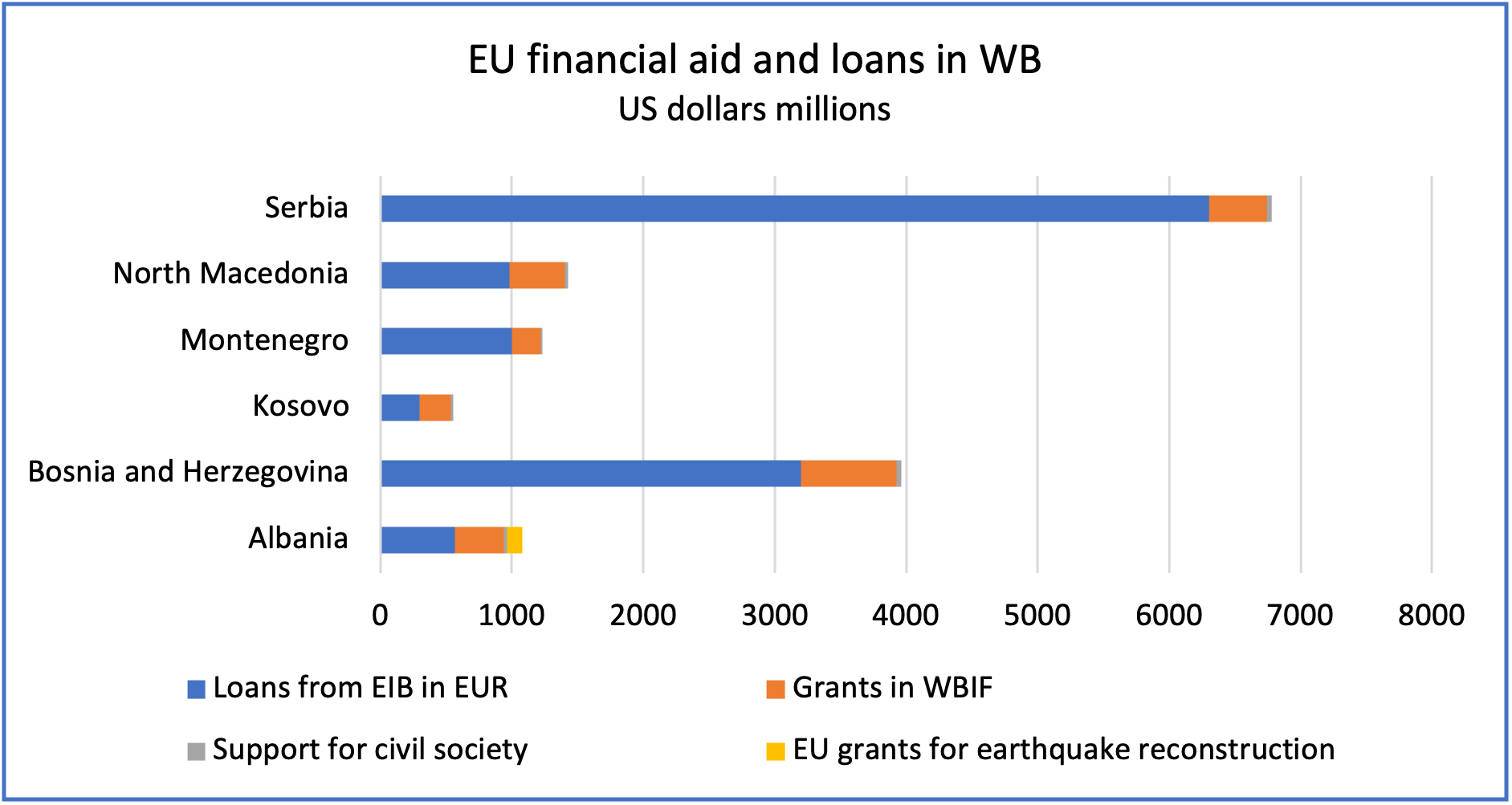

The EU is not only the biggest trade partner for a total of EUR 53 billion and investor for EUR 3.3 billion of new investment in 2021 in the Western Balkans, but also the largest provider of financial and development assistance in the region for a total of EUR 15 billion since the start of the EU integration process. (Figure 11)

Source: European Union Commission fact sheets on EU enlargement

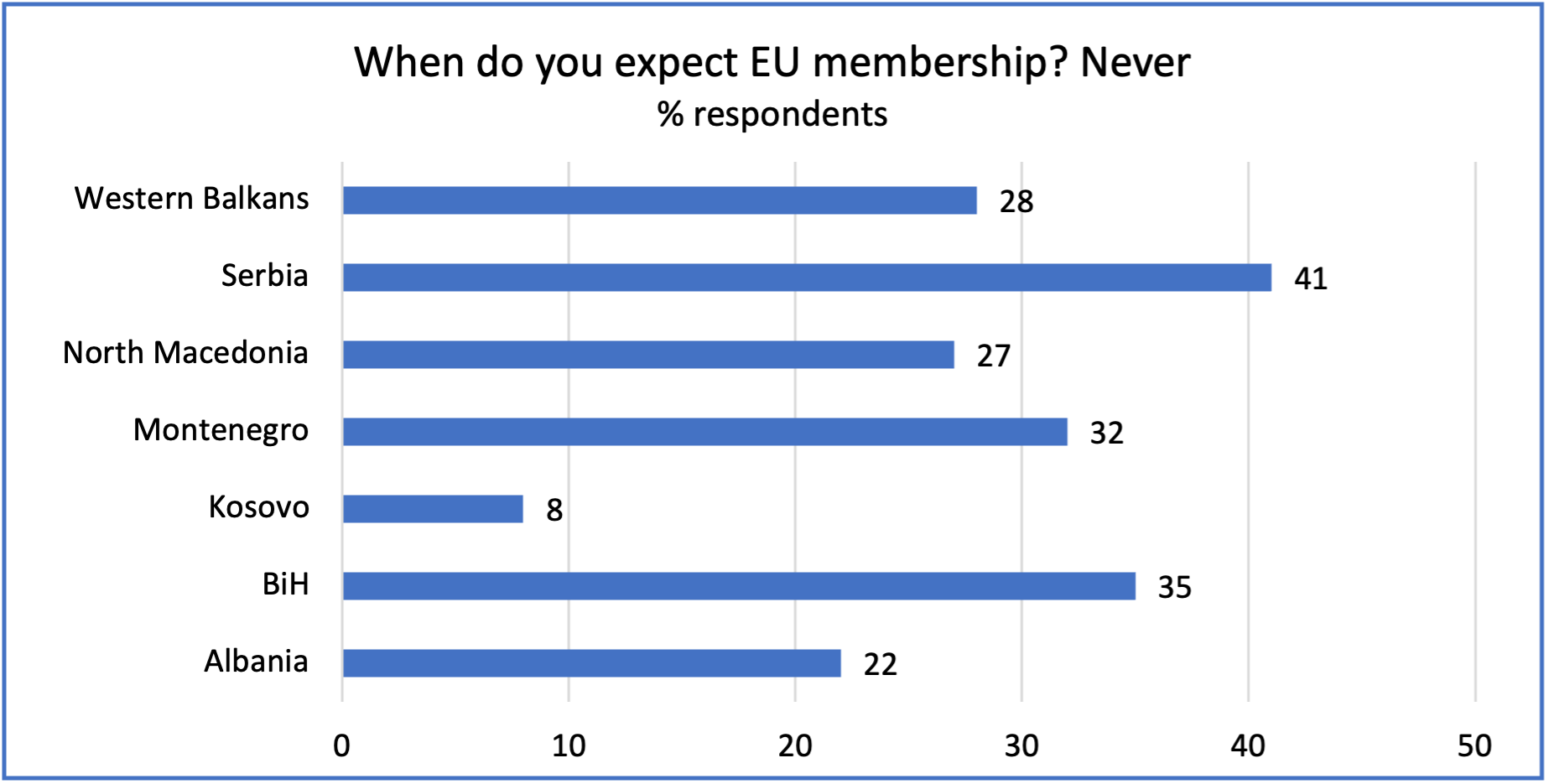

EU membership is supported by the majority of citizens across the Western Balkans, with 60% endorsing the accession process, according to Balkan Barometer polls. However, when it comes to expectations of citizens, polls indicate a more sober outlook, with only 22% of citizens remaining optimistic about EU accession by 2025. 37% believe that 2030 would be the last deadline for EU integration. What is even more dangerous is that the number of participants who consider membership to the EU a mere velleity instead of a realistic scenario is continuously rising with 28% being very sceptical. By far, the EU is leading as the most preferred economic partner of all Western Balkan countries (average 69%) over other markets such as Turkey (41%), China (35%) and Russia (33%). (Figure 12 and 13)

Source: Balkan Barometer, Regional Cooperation Council, https://www.rcc.int/download/docs/2020-06-Balkan-BarometerPublicOpinion_final.pdf/bf27f9fc10de8a02df9db2b60596f0cd.pdf

Source: Balkan Barometer, Regional Cooperation Council, https://www.rcc.int/download/docs/2020-06-Balkan-BarometerPublicOpinion_final.pdf/bf27f9fc10de8a02df9db2b60596f0cd.pdf

In line with its geo-economic and diplomatic vision, Beijing is promoting its economic model of “capitalism with Chinese characteristics[54]”, utilizing its capital as an “economic miracle-maker,” primarily using economic and financial tools. More specifically, since 2013 the ambitious BRI (a brain child of President Xi Jinping) has been used as a foreign policy narrative to export the “China Dream”, cemented into the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party at the 19th Party Congress, spelling out the new Chinese international vision aiming to place China as a leader power on the global stage, with a greater ability to shape global rules, norms, and institutions, exporting its own economic model, and increasingly challenging the West about the current rules based international order.

The tremendous growth of the Chinese economy since the 1990s, by a factor of 12 from $400 billion in 1990 to $17.5 trillion in 2021 has turned China from a developing country into an economic superpower, making Chinese leaders more confident about creating narratives and promulgating the superiority of their system over the Western-led liberal economic system. As a result, the EU named China a “systemic rival” promoting alternative models of governance at the EU Commission’s “EU-China: A Strategic Outlook,” published in March 2019[55] and the United States considers China as more assertive, and as a competitor “potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system” in its Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,[56] published in March 2021.

One of the main questions is how much of a challenge does China pose to democratic developments in the Western Balkans. The Copenhagen Criteria, the essential criteria for the Western Balkans to become EU members, are divided into three main groups: 1) Political criteria: stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights as well as respect for and protection of minorities; 2) Economic criteria: a functioning market economy and capacity to cope with competitive pressures and market forces; 3)Administrative and institutional ability to take on obligations of membership (Acquis Communautaire)[57]. The revised accession methodology puts an even stronger focus on fundamentals, rule of law, economic criteria, and public administration reform[58] and is divided into six negotiation clusters: fundamentals; internal market; competitiveness and inclusive growth; green agenda and sustainable connectivity; resources, agriculture, and cohesion; and external relations.

Fundamentals first: How is Chinese influence affecting democratic developments in the region

Principles of fundamental human rights are key to the functioning of democracy and are at the core of the EU principles and institutions, and enriched in the Charter of the Human Rights of the European Union[59], and according to The Treaty of Amsterdam the constitutional principle of “'The Union is founded on the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law, principles which are common to the Member States”[60] this is key to the enlargement process. In the accession process, Chapter 23 is one the most challenging ones and affects progress in all other aspects of negotiations with the EU.

Chapter is divided into four main areas: judiciary, fight against corruption, fundamental rights, and the rights of EU citizens[61]. In the new EU approach to enlargement, chapters 23 and 24 (fight against organized crime) and the first to be opened and the last to be closed. Chinese standards on freedom of expression and fundamental human rights deviate substantially from those of the EU, with China ranking 175 out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index.[62] The Western Balkan counties continue to perform low in this area, with some even showing a downward trend.

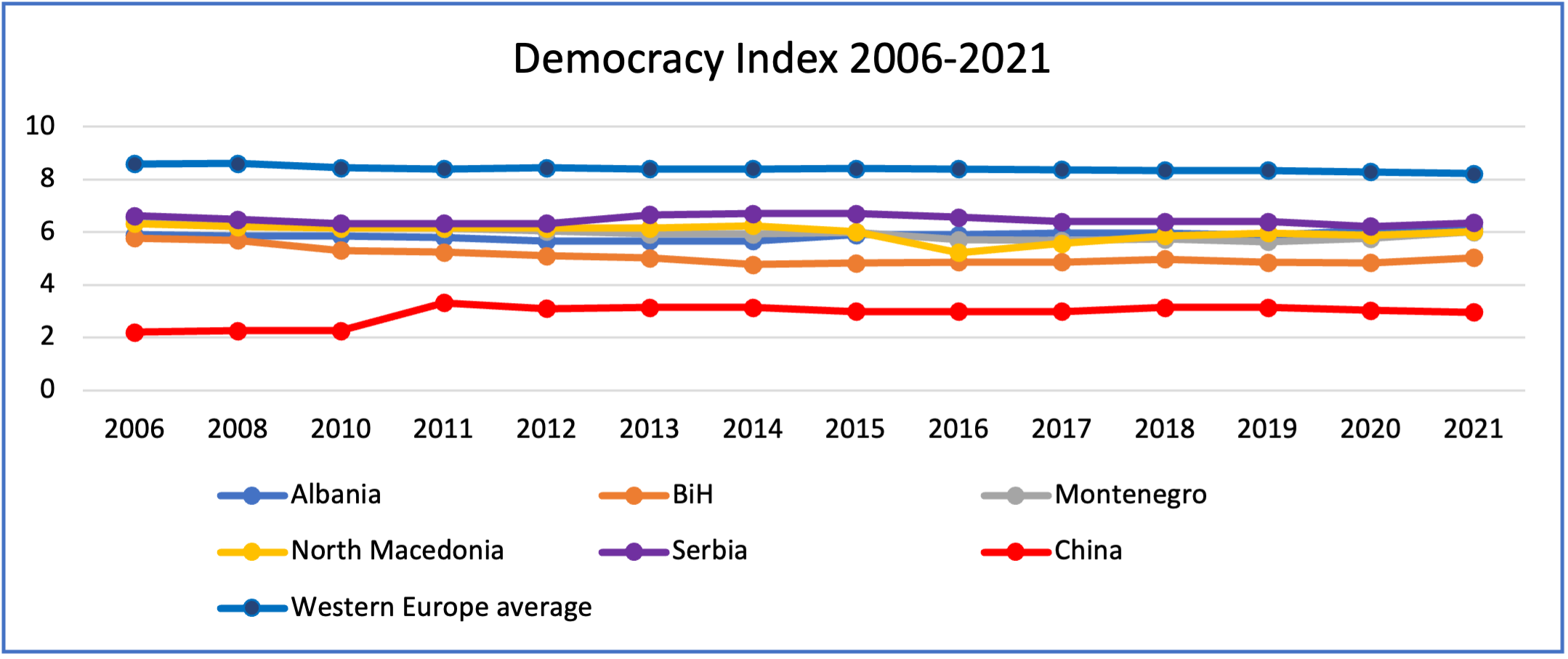

The Chinese state-led authoritarian system has played a major role in integrating the Chinese economy into the global capitalist system. In the Democracy Index, China is classified as an “authoritarian regime”, with a total score of 2.21 (considering the 0 to 10 scale), sitting in the bottom of global rankings at the 148th position out of 167 countries. The countries of the Western Balkans are considered “flawed democracies” ranking from the 63rd place of Montenegro, 68th Albania, and North Macedonia and Montenegro at the 73rd and 74th place respectively at the bottom of the group. BiH is considered a “hybrid regime” ranking at the 95th place. In the Western Balkans, formal democratic institutions and mechanisms co-exist in dual systems with poor functioning of governments, high levels of corruption, and lack of transparency, resulting in low trusts in governments. What is concerning is three countries, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia have seen a visible decline of the scores over the last ten years, showing a visible democratic backsliding. (Figure 14)

Source: Democracy Index, Economist Intelligence Unit

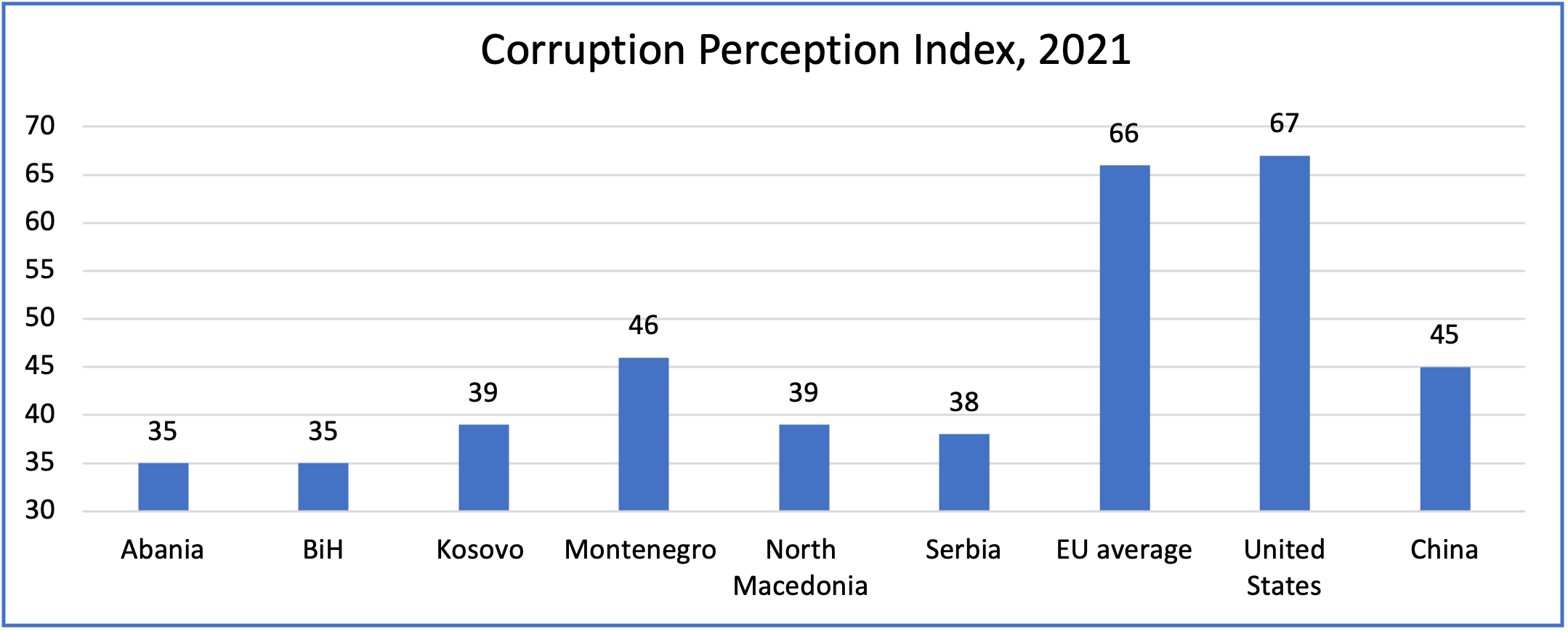

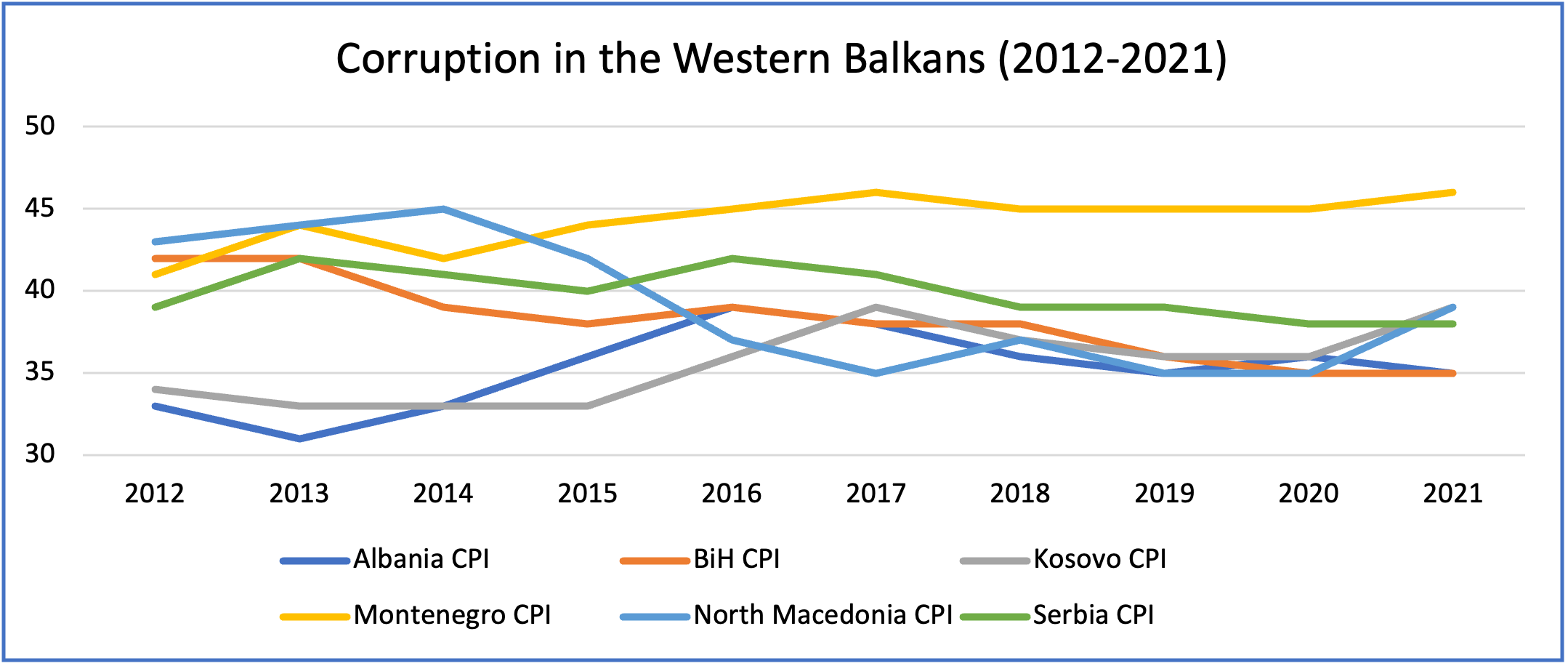

Another challenging issue related to China’s increased influence in the Western Balkans is related to corruption, which a rampant problem that hinders the economic and democratic development of the region and threatens the rule of law. China’s economic approach in the region could become problematic, and hinder good governance. In China, lack of democratic scrutiny and accountability, self-serving elites, and abuse of power has allowed corruption to flourish. In fact, the “common prosperity” political campaign of President Xi has focused on anti-corruption and anti-poverty policies. China ranks on the 66th position out of 180 countries with a CPI score of 45 (from 0 to 100 the cleanest) compared to the average score of the European Union of 66. In the Western Balkans countries rank from the 64th position of Montenegro, followed by North Macedonia in the 87th, Serbia in the 96th position, and Albanian and Bosnia Herzegovina, both in the 110th position. (Figure 15)

Source: Corruption Perception Index, Transparency International (CPI from 0 to 100 where 0 is the worst and 100 is

the best), https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/index/chn

The inflow of external financing from authoritarian countries to emerging democracies lacking transparency, accountability and market orientation, without the proper checks and balances in place, can promote corruption and undemocratic practices. Not having to comply with transparent tendering procedures, accountability and other elements of governance reform, but still receiving much-needed capital, makes leaders in the region less dependent on the EU, and enables them to preserve their vested economic interests. Almost all the countries of the region have registered big declines in their CPI scores, with some falling up to 30 places in the Transparency International rankings. (Figure 16)

Source: Corruption Perception Index, Transparency International (CPI from 0 to 100 where 0 is the worst and 100 is the best), https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/index/chn

The EU cluster on fundamentals also includes the reform of public procurement (chapter 5). In order to integrate with the EU single market it needs to facilitate open market competition, be transparent and accountable, and operate on basis of equal treatment. In the case of large Chinese infrastructure in the region, public procurement laws have been bypassed and implemented on bilateral government agreements and under special laws, without any transparency for the public,[63] as seen throughout the region.

Privacy and data protection standards involving Serbia’s cooperation with Huawei, specifically its ‘Safe City’ project, promotes collection of mass video surveillance and facial recognition software. In 2017, Huawei signed a contract with the city of Belgrade to provide “Safe City” surveillance equipment to Serbian cities consisting of 1000 high-definition cameras in Belgrade alone and to establish the Huawei Innovation Center for Digital Transformation. Such activities related to the application of Chinese telecommunications equipment and software in defence and security systems are perilous trends. This raises questions regarding compatibility with EU standards on privacy and data protection, as enshrined in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).[64]

Economic standards for EU membership and Chinese “debt trap” diplomacy

Western Balkan countries should abide by the EU’S Stability and Growth Pact (chapter 17 on economic and monetary policy), which regulated standards on debt that should not exceed 60% of the GDP, and budget deficits that should not exceed 3% of the GDP. High foreign debts may lead to debt distress, with negative financial, economic, and social consequences, including cuts of the government spending and increased interest rates. The quick Chinese money and lending opportunities for infrastructure projects with “no strings attached”, meaning no distinctions between authoritarian and democratic governments and without conditioning lending on good government and transparency (as in the case of Western banks and EU institutions), are burdening the poor governments in the region with large debt obligations considering the unsustainable deals and the lack of due diligence, as sovereign guarantees shift risk onto host countries, at the expense of their financial stability and risking to get trapped in debt servitude with China. In addition, by providing easy money, the Chinese financial institutions diminish the appeal of EU oriented reforms and the power of EU conditionality by providing capital for economic development. As a result, Chinese capital is more likely than Western capital to fuel corruption, bad governance, and projects that deviate from EU standards.

China’s lending to governments in the Western Balkans mainly takes place through the China export-import bank (China EXIM), a state-funded and state-owned policy bank whose main task is to support China’s foreign trade, investment and international cooperation, which mainly funds up to 85% of the project, and Chinese SOEs are always the general contractor, using Chinese equipment and labour force.

Although much needed, these infrastructure projects and Chinese lending agreements, are usually awarded directly to Chinese SOEs in secret single-bid contracts without international public tenders, offering those profits from unsustainable deals, while allowing for the spreading of Chinese labour and environmental standards, distinctly weaker than EU standards.

On the other side, the Chinese backed projects can easily be aligned with political cycles. When coupled with top-down, rather than market-driven procurement decisions, China’s offer allows Balkans decision-makers to fuel patronage networks and boost short term electoral advantages by focusing on short term unsustainable economic growth. Chinese quick money may seem an easy way for many leaders in the Western Balkans to maintain power, and the political alignment of most regional media has not allowed broader public discussion of China’s activities in the region.

Montenegro is the perfect case study in this regard, as the Bar-Boljare highway, linking the port of Bar in the Adriatic Sea with Serbia is financed from China’s Exim Bank for almost 1 billion for only the first section of the highway (41 out of 165km), built from China Road and Bridge Corporation (RBC). The most expensive highway[65] per km in the world (at USD 20 million per km) had sent Montenegro’s sovereign debt to a staggering 107% of the GDP in 2020 (down to 86% in 2021).[66] The deal between the Government of Montenegro and China’s Exim Bank is not public, but there are allegations of strange terms, such as giving up sovereignty of lands in case of missed payments and financial problems. Even arbitration would take place in China, using Chinese laws. Two separate feasibility studies both concluded that this project was not economically viable,[67] and based on government estimates, the remainder of the Bar-Boljare highway will cost an additional $2 billion.[68] A European financial institution is prepared to help refinance Montenegro's $1 billion debt to China, which the Balkan country incurred over a controversial highway project. A refinancing agreement could bring to an end the uncertainty over Montenegro's debt with China and shore up its relations with the EU, for the unfinished project.

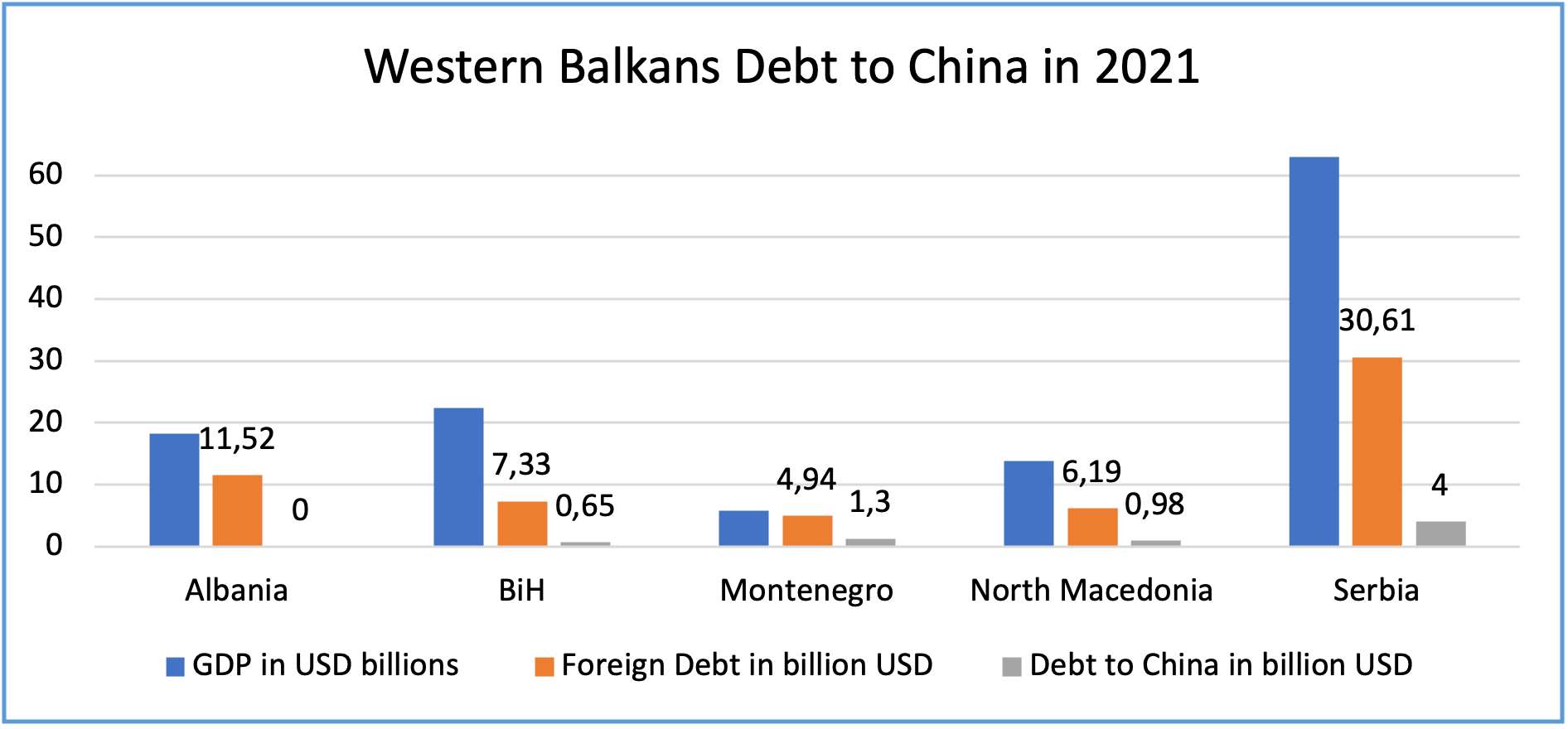

In the Western Balkans, the Chinese lending goes from 27% of the foreign debt and 22% of the GDP in Montenegro, to 16% of the foreign debt and 7% of GDP in North Macedonia, to 13% of the foreign debt and 6% of GDP in Serbia, to 8% of the foreign debt and 3% of GDP in Bosnia and Herzegovina[69] in 2021. (Figure 17). The more countries are indebted to China, the higher the risks that Beijing could attempt to renegotiate loans in exchange for furthering its diplomatic and political objectives, without excluding possible asset seizures as evidenced in other BRI countries.

Source: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/albania/external-debt; https://www.research.unicredit.eu/DocsKey/emergingmarkets_docs_2021_179967.ashx?EXT=pdf&KEY=l6KjPzSYBBGzROuioxedUNdVqq1wFeRoBg8dvzn51cwxIFTj0Rbl4w==&T=1; https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/April/weo-report?c=914,963,967,943,962,942,&s=GGXWDG_NGDP,&sy=2021&ey=2021&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

EU’s standards on green agenda and energy

China, a large exporter of coal, is funding coal-plant investments in the Western Balkans contrary to EU goals for the region. Coal related projects in fact have been refused to be financed by European development banks or the World Bank in an attempt to address environmental concerns and support the production of green energy. This, in spite of the fact that the region remains one of the most polluted in Europe and still dependent to a large extent on low-level lignite coal for electricity production. The Western Balkan countries are not technically bound by EU environmental standards, but plants will need to be retrofitted in order to continue operations if EU membership is secured. This was a case that led to an EU procedure against Bosnia and Herzegovina in which a Chinese loan for coal powerplants in Tuzla was deemed to be non-compatible with EU state aid rules.

While, these countries have committed to adopting EU’s energy and transport acquis and related standards, implementation is very poor as a result of weak institutions and vested economic interests. The EU requires coal plants to comply with its ‘Best Available Techniques’ standards under its Industrial Emissions Directive, which would require tremendous investments. Additionally, with EU plans for a new green deal underway, a more costly EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) would be a death knell for the business models of these polluting coal plants. The Chinese economic engagement in the region hence allows the Western Balkans to avoid costly EU environmental standards in the short run, while undermining their EU integration path.

The Western Balkans have joined the Energy Community Treaty (ECT)[70] as contracting parties, which is designed to bring the environmental policies and pollution standards of these countries in line with those of the EU. The objective is to work towards new legislation in the Western Balkans to support market integration and decarbonization, starting with the adoption of the Decarbonization Roadmap and five key legislative acts stemming from the EU’s Clean Energy for all Europeans package (CEP). This reality is even more pressing given the fact that EU regulators have laid out a blueprint for half of Europe to be powered by renewable energies by 2030.

Environmental sustainability is one of the standards by which European investment banks decide on their funding. So, the EU has not provided funding for polluting coal plants. China, a large exporter of coal and itself heavily reliant on coal plants for energy, is providing the region with an alternative to the EU by funding coal-plant investments.

Foreign, security and defence policy: a very important cluster for EU integration

While it seems that China is not interested in internal political matters of the countries where it invests, the issue is different about the positions that these countries take on issues such as China’s human rights record in Tibet or Xinjiang and its policies towards Taiwan and Hong Kong, using its economic carrot to coerce these governments or sticks to retaliate against any country that criticizes its policies. An example is when Lithuania, one of the former members of the “16+1” initiative, allowed the opening of a Taiwanese representative office in its capital, called a “Taiwanese” institution as opposed to a “Taipei” institution, being perceived as a dangerous and provocative step by Beijing which responded with tough economic coercion actions.[71]

In 2019, a group of 22 countries (including United States, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and others) at the United Nations’ human rights body issues a joint statement condemning China and urging it to end its “mass arbitrary detentions and related violations against Muslims in the Xinjiang region in “re-education camps,” and called on Beijing to allow UN experts to access the region.[72] None of the Western Balkan countries joined this letter. A statement duel followed at the U.N, when a group of 37 countries submitted a similar letter in defence of China’s policies, where signatories expressed their opposition to “politicizing human rights”, reiterating Chinese rhetoric in calling those “vocation education and training centres[73].” This letter was followed by a second one in August 2019, with additional signatories in defence of China, for a total of 50 countries, that included Serbia as a signatory[74]. In October 2002, the German Ambassador Heusgen presented another statement to the U.N., within the context of the General Assembly’s Third Committee (on Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Issues) on behalf of 39 countries, calling again on China to “respect human rights, particularly the rights of persons belonging to religious and ethnic minorities, especially in Xinjiang and Tibet.” Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia signed this letter. In response, Cuba’s U.N. Representative read a statement on behalf of 45 countries in defence of Chinese policies, but Serbia was not part of that list.

All the five Western Balkans region adhere to a One China policy by refraining from political interaction with Taiwan, the extent to which they support China on other issues, such as matters relating to Xinjiang, Hong Kong and the South China Sea, has remained limited. Albania began to develop relations with Taiwan in 1999 establishing an Association of Friendship of parliaments, but it was closed down in 2000 when in a joint communique with the PRC where the Albanian government reiterated its support for the “One China” policy and stated that it would “not establish official ties or conduct official contacts with Taiwan in any form”.[75] North Macedonia established diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 1999, but China immediately launched a diplomatic retaliation when it used it veto power at the UN Security Council to veto the mandate for the extension of a UN preventive deployment force. In 2001, the government of North Macedonia (at that time known as FYROM) declared to recognize PRC as the sole legal government of China, and relations were re-established.

The absence of critical voices from the region towards China indicate that the Western Balkan countries put their interests first when dealing with China and therefore remain wary about criticizing it over human rights or other issues that the Chinese government regards as sensitive.

When it comes to Hong Kong, Serbian officials have supported China's position on Hong Kong, but have refrained from comments on the South China Sea issue, beyond calling for a peaceful settlement. Milorad Dodik, the Serb member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has expressed support for China over the issue of Hong Kong.[76] Montenegro's foreign ministry issued a statement on the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague on the dispute between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea, classifying the Philippines’ appeal as a unilateral measure and calling for dialogue instead.

Kosovo, which is not recognized by China, as according to the Chinese government its unilateral declaration of independence conflicts with the Chinese principled approach to territorial integrity, and Beijing has used its influence several times, not only at the UN Security Council but also to prevent Kosovo’s participation in international organizations, such as in 2015 when it voted against Kosovo’s membership at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),[77] and also in 2017 Kosovo rescinded its Interpol application as the assembly was hosted in China.[78]

How should the EU respond to China’s increased influence in the Western Balkans?

The EU is engaged in an intensive project of stabilization and integration of the Western Balkans with the aim to foster peace, stability and prosperity of the region. With the membership perspective, first announced in the 2003 Thessaloniki Summit, the EU aims to spur reforms in line with its norms and values focusing on the Copenhagen+ Criteria. These reforms include key political, economic, and institutional requirements for aspiring members, but also criteria on fostering regional cooperation. The European perspective of the region is viewed in the mutual strategic interest and remains a shared strategic choice. As EU President von der Leyen reiterated at the EU-Western Balkans Summit held in Zagreb in May 2022, saying that “The Western Balkans belong in the EU”.[79]

European policy makers have raised concerns in the past years that “the Balkans can easily become one of the chessboards where the big power game can be played”, starting with former High Representative Federica Mogherini in 2017[80] and this topic was also part of the EU-Western Balkans Summit held in Slovenia in October 2021 where EU President Charles Michel stated in his meeting, that the EU must pursue its own interests on the global stage “in particular vis-à-vis China”.[81]

EU’s response to China should be based on the reality on the ground that the Western Balkan countries will continue to welcome Chinese economic and infrastructure development opportunities, to calm the big gap they have with the Western European countries. In this respect, the EU and its members states should incorporate China-specific goals and mechanisms in their enlargement policy. EU’s goal should not be to limit Chinese investment, but to make sure that new business practices that these bring with them do not undermine the possibilities of EU membership for the region. While China’s increased footprint in the region may not mount a fundamental challenge to the European integration process and regional stability, its “state-capitalism” model definitely could challenge EU’s normative power in the region. Chinese increased influence in the region could challenge European business interests, and fuel practices that distort efforts of the EU to enhance promotion of western norms and democratic standards and combat corruption.

To prevent any potential destabilization in its backyard, the EU needs to re-affirm its “open door policy”, speed up the negotiation process for candidate and aspirant countries. The technical process of accession negotiations needs to be supported politically, to send positive signals about the European future of the region, to inject more certainty and predictability, but also to keep governments in the region more transparent and accountable. Further delays run the risk of declining the natural attraction towards the EU and creating space for competing alternative visions.

The enlargement process should be seen as a win-win situation, and should be focused on a visionary and pragmatic cost-benefit analysis as a rational basis for reinvigorating the process to deliver tangible results. Stability, security, and democratic prosperity in the Western Balkans is deeply linked with the security and resilience of the EU. This is all more important in light of the new security environment in Europe. Russia’s brutal war in Ukraine and its disruptive behaviour, China’s challenging and assertive economic influence, the global pandemic, the crushing energy crisis and the economic recession, the climate emergency, and rising nationalism and receding democracy, all require the EU to include the Western Balkans in the European family of democratic states that share the same norms, values, and standards.

Promoting development and economic rule of law in the Western Balkans is an urgent task for the EU, and can be best done by gradually integrating countries of the region in the European internal common market, through phasing procedures, once countries are aligned with the economic policies and criteria regulating the internal market cluster.[82] In this respect, to reduce the gap in structural funds between member and candidate countries, the Western Balkan countries should be allowed earlier access to EU structural funds to promote economic and social development, more infrastructure projects to improve connectivity and easier access to the internal market, to reduce reliance on Chinese sources of finance, to improve institutional capacities, and promote regional cooperation.

The Western Balkans need a EU-driven economic development, as chapters are opened and negotiated with more access to the EU budget, entry into the single market and the customs union, but also serious support for innovation and industrial development in the region. The EU will invest $10,5 billion (EUR 9 billion) in the region for 2021-2027, to help bring their economies in line with EU standards, to support economic convergence with the EU through investments and support to competitiveness and inclusive growth, human capital, sustainable connectivity, and the twin green and digital transition.[83] The Economic and Investment Plan[84] for the Western Balkans is designed to help develop transport and energy infrastructure to foster economic growth and employment. It aims to unleash the untapped economic potential of the region and the significant scope for increased intra-regional economic cooperation and trade.

More funds are needed in the Western Balkans. The region was included in the strategy of the EU Commission published in September 2018 “Connecting Europe and Euro-Asia”, seen as a blueprint for connectivity and infrastructure development based on Western economic and institutional norms and principles, but despite bold ambitions, the proposal was not backed by funding.

In December 2021, the EU Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, introduced “The Global Gateway” strategy as a much-needed step outwards for the EU in investing strategically worldwide. This is a massive investment platform of sustainable and quality projects in infrastructure and skills, in line with the green and digital transition that plans to mobilize $340 billion between 2021-2027, with $150 billion of financing for guaranteed investment for infrastructure, $20 billion in grant funding from the EU budget, and another $160 billion of planned investment from European financial and developmentally-focused financial institutions.[85] This is where the Western Balkans should take a prominent role in attracting infrastructure funds.

While increasing the financing for infrastructure projects, funding should be linked to clear demands for the region’s alignment with EU foreign policy goals on China. Some leaders in the Western Balkans use their stronger relations with Beijing also as an opportunity to assume a more visible role in the European stage and play the card of “other alternatives” to the EU.

The EU should condition the enlargement process with the demand to increase the transparency of Chinese projects, and allow for greater levels of public scrutiny of their promised benefits. Similarly, the application of the EU FDI Screening Mechanism and the new “Regulation on Foreign Subsidies distorting the Internal Market” should be extended to the Western Balkans conditions for the EU accession process, to better scrutinize investments in the strategic sectors in the Western Balkans economies.

In this framework, accession chapters that provide for higher quality regulatory environment for infrastructure projects, including public procurement standards and environmental and social impact assessment rules. Similarly, Chapters 23 and 24 related to the rule of law and justice will limit potential for corruption. A more structured and stringent insertion into the EU accession process of policies and issues relating to environmental and procurement standards, economic governance, and debt sustainability, will build capacity of governments in the region. It will also allow Western institutions to be in a better position define counter-strategies and increase transparency regarding Chinese G2G contracts, debt overreach, and other numerous hidden conditionalities.

The EU should assert its own model of governance and not allow China, or other external powers, trade space to nullify the region’s fragile reform progress. This will help to put existing and future Chinese projects on a more sustainable footing, and prevent China’s economic initiatives from degrading opportunities for economic growth and society-wide benefits. This is essential to help build the region’s economic, institutional, and democratic resilience, a key EU objective for the EU.

The EU institutions and member states must recognize and appreciate the weak local capacity to understand and manage the environment, financial, and social standards and the high costs of compliance in the Western Balkans. In this respect, the EU should support capacity building in the region for public officials in the central and local government structures for the implementation of the EU rules and standards. The private sector consultancies could play an important role in supporting public administration, and the EU should foster mechanisms of public-private partnership. Better funding opportunities and coordination between EU and Western Balkan countries should also be available. The EU should finance research in the Western Balkans related to the Chinese influence in the region, and conduct regular surveys/polls on how people in the region view the influence of China.

In addition, there is a strong need to improve the visibility of the EU-backed funding with better strategic communication strategies in the Western Balkans. The EU Commission and the EU Delegation Offices in the Western Balkans should do a better job communicating with the wider public and the civil society.

Endnotes:

[1] Zeneli Valbona, “The Western Balkans low hanging fruit for China”, The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2020/02/the-western-balkans-low-hanging-fruit-for-china/

[2] IMF WEO database

[3] https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2020.pdf

[4] https://www.natofoundation.org/western-balkans-dossier-the-unviable-economies%E2%80%8B/

[8] https://china.balkaninsight.com/

[9] https://china.balkaninsight.com/

[11] https://www.ft.com/content/3e91c6d2-c3ff-496a-91e8-b9c81aed6eb8

[12] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-albania-everbright-idUSKCN1271ZE

[14] https://bankwatch.org/project/tuzla-7-lignite-power-plant-bosnia-and-herzegovina-2

[19] https://www.ekinmaden.com.tr/en/about-us/

[20] AidData. 2021. AidData's Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0. Retrieved from https://www.aiddata.org/data/aiddatas-global-chinese-development-finance-dataset-version-2-0

[21] R. Turcsanyi (2019),’ Friends or Foes? How Diverging Views of Communist Past Undermine the China–CEE “16+1 platform”’, Asia Europe Journal.

[24] Ying Zhou & Sabrina Luk (2016) Establishing Confucius Institutes: a tool for promoting China’s soft power?, Journal of Contemporary China, 25:100, 628-642, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2015.1132961

[26] https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/590/text

[27] https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200513092025679

[28] https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/sarajevo/16005.pdf

[29] https://www.rferl.org/a/china-balkans-ties-using-serbian-universities/31249503.html

[31] http://nubsk.edu.mk/en/services/users/confucius-institute

[33] https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/ceba//eng/gdxw_10/t1577627.htm

[34] https://www.csust.edu.cn/info/1264/5966.htm

[35] http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-10/11/c_137523906.htm