Vladimir Nikitovic, a demographer at Belgrade’s Institute for Social Sciences, thinks of himself as an optimistic person — but not when it comes to Serbia’s population projections.

"It’s too late!" he said. "It’s not [that it’s] too late now. It was too late even 20 years ago!"

Nikitovic has been going over the demographic figures for Serbia and they make for grim reading.

His predecessors, working in the same building that he works in today, had even warned Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia’s leader who died in 1980, about what was happening. Serbia’s demographic decline has been clear to demographers at least since the 1970s.

Then came the breakup of Yugoslavia and the wars of the 1990s, "and everything got worse," Nikitovic said.

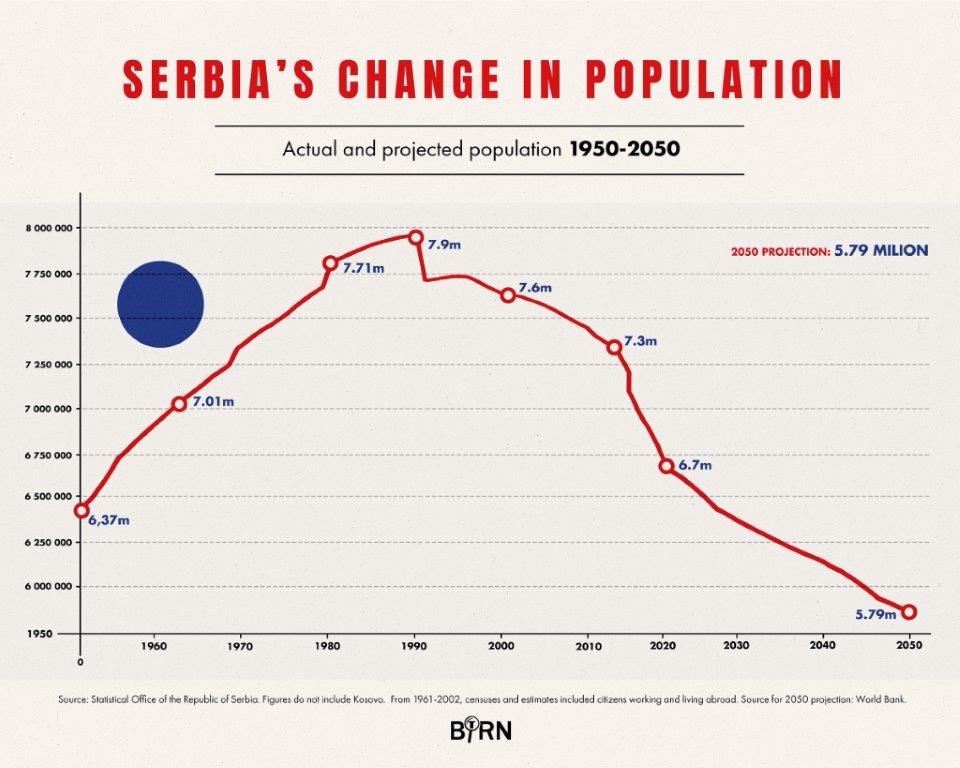

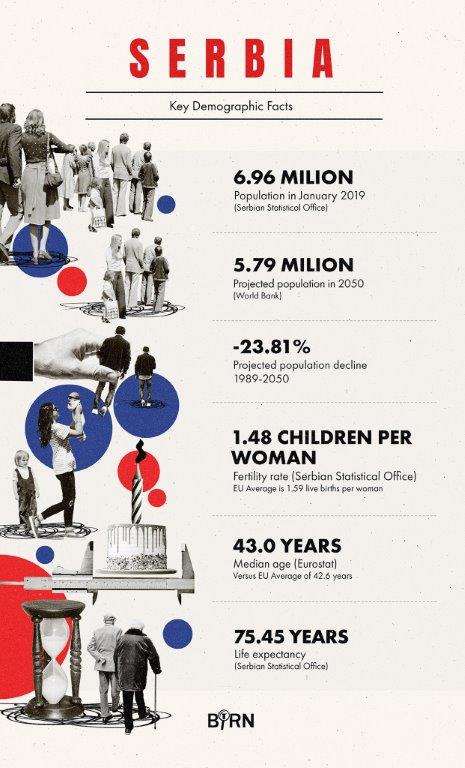

Serbia’s population was 6.96 million at the beginning of 2019, according to the Serbian Statistical Office. The figure excludes Kosovo, although Serbia does not recognize its independence.

In 2018, there were 63,975 live births and 101,655 deaths so, disregarding how many actually left the country in this period, Serbia’s population declined by 37,680 people.

That was the worst figure in a decade, in which the average population decline was 35,125 a year.

In the dry language of the Statistical Office, the “natural increase rate” of Serbia’s population in the decade was -5.4 percent. In plain language that is a decrease.

In the Yugoslav period what was happening in Serbia was unclear to non-specialists. The reason for this was that there were enormous regional variations across the country.

Today, Serbian women give birth to an average of 1.48 children, well below the 2.1 needed just to maintain a country’s population.

But a low birth rate among Serbs is not new. Serbia, not including Kosovo, slipped under the replacement rate as early as 1956.

|

"We are one of the regions in Europe which was the first to face the end of the baby-boom period and it struck us heavily by the 1990s," Nikitovic said.

Before the collapse of Yugoslavia, however, birth rates remained high in poorer regions and this served to mask what was happening in Serbia, where the fertility rate was also very different if Kosovo was included and where women had an average of 7.6 children in 1950 and 5.6 in 1972.

But the birth rate was not the only reason why the drama of what is happening today in Serbia was not clear to most people.

Another reason is that in the three censuses of 1971, 1981 and 1991, officials sought to massage the figures to mask the huge numbers who worked abroad due to a lack of work at home.

Officially there were 7.82 million people in Serbia minus Kosovo in 1991. In fact, that figure was boosted by 283,000 people who were not there. By this time, about 1 million Yugoslav citizens lived abroad as so-called Gastarbeiter or their family so the population census for Yugoslavia and its constituent parts overstated population figures. In 2002, Serbia reverted to the international norm of only counting those who actually lived in the country.

Taking all this into account, Serbia’s population has shrunk by 8.42 percent since the demise of Yugoslavia.

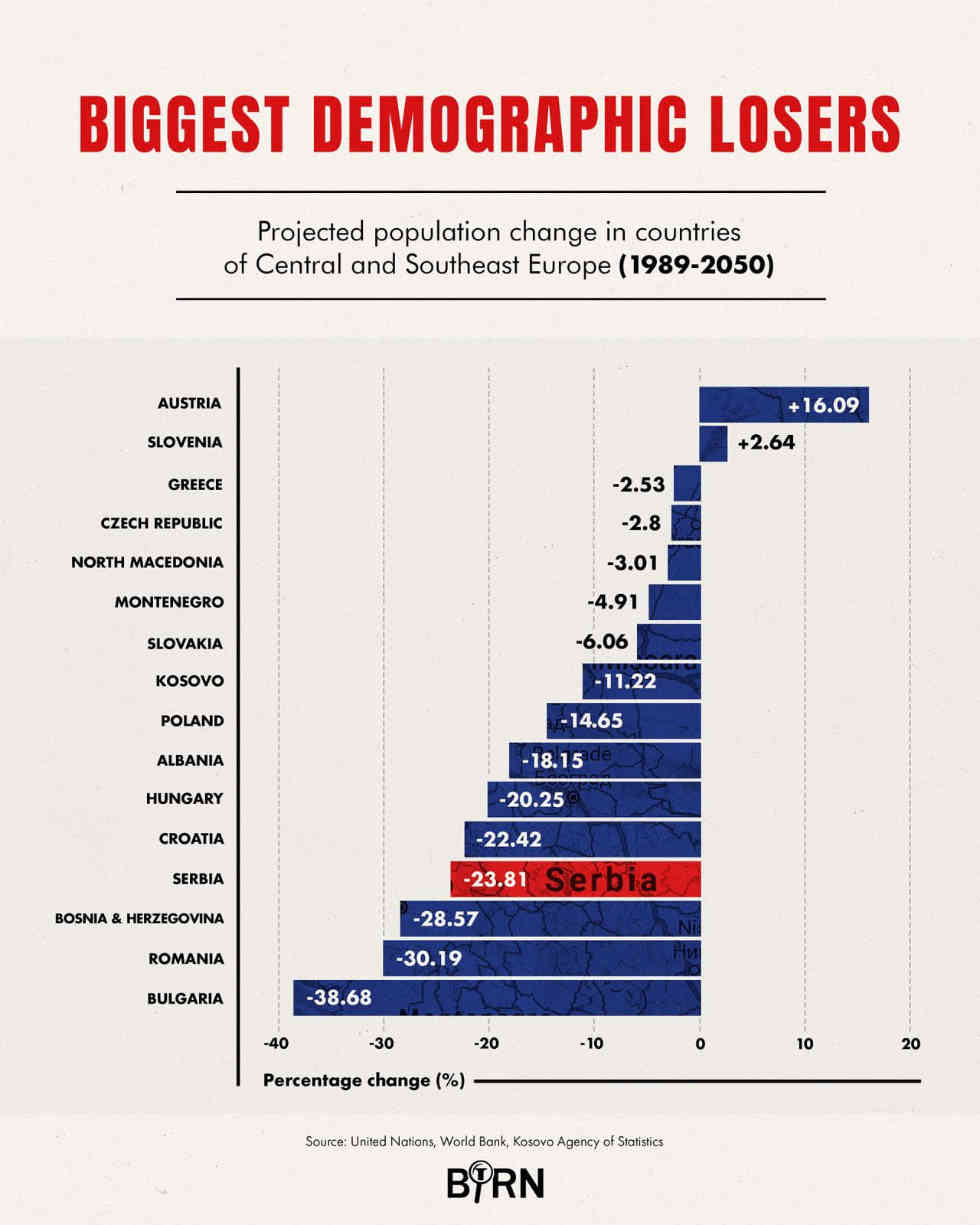

The World Bank predicts that on current trends it will be 5.79 million by 2050, which would mean a 23.81 percent decrease in the same period.

Not only does Serbia suffer from a low birth rate but its population is also elderly. Serbia’s median age is 43 and the EU average is 42.6. However Serbia, unlike most Western countries, has no immigration to make up for lost workers.

That is not to say no one is coming to live in the country at all. Net emigration is 15,000 to 20,000 a year. This means that while 40,000 to 50,000 leave every year, 30,000 or so come back, Nikitovic said.

While the returnees include those who only went abroad for a short period, they also include an average of some 10,000 to 15,000 pensioners a year, former Gastarbeiter now retiring, whose children, however, rarely come back with them.

The wars of the 1990s also skewed figures.

Serbs who came from Kosovo do not show up in the statistics as they were already citizens of Serbia but some 600,000 refugees who came from Bosnia and Croatia do.

However, only 375,000 to 400,000 of the refugees stayed while others eventually went home or elsewhere, Nikitovic said. But roughly the same number of people also left Serbia during the wars.

The demographic effect was not favourable as it was mostly younger people who left Serbia while it was families and older people who arrived. The result was that "if you look at the age structure, it is worse than it was before the dissolution of the country," Nikitovic said.

Serbia’s authorities are well aware of the demographic crisis, the labour shortages it is beginning to create and the ongoing problem an ever older population creates for the pension system.

In 2021, according to the Statistical Office, Serbia will have more pensioners than working age people.

Likewise, emigration of the young, the skilled and the hard-working is only set to worsen.

In the past it was EU accession that really opened the doors to the emigration of people of working age. Now Germany and other countries have relaxed the rules meaning that it is easier than ever for Serbs to work abroad legally.

As long as Serbia remains an unattractive country for potential immigrants, its population will continue to age and decline, a prospect that also means that it makes it ever harder to catch up in terms of wealth and standards of living with Western countries, which means in turn that they remain as strong a magnet for immigration from Serbia as ever.

The article gives the views of the author, not the position of the "Europe’s Futures

Ideas for Action" project or the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM).