In the course of the recent dramatic events in Ukraine, great emphasis has been put on the language question. In this essay, I intend to clarify some crucial issues: I will demonstrate that Vladimir Putin’s allegations regarding the suppression of Russian speakers in Ukraine are part of a complex network of continuing propaganda, and I will confirm that Putin’s recent political moves are the result of an ideology that is dangerously close to that of Nazi Germany.

1. The Kremlin’s attitude toward Ukraine in a nutshell

In 2008, Russian President Vladimir Putin declared that “Ukraine is not even a state”, after labelling the breakup of the Soviet Union as the “greatest geopolitical disaster of the last century” in 2005. In January 2009, when the Russian “gas war” against Ukraine reached its peak, Putin routinely ridiculed Ukrainian identity, calling it a matter of “lard and vodka” [“сало и горилка”] (“Moser Gaskrisendiskurs”). In addition to the Soviet past, Putin has at times used symbols of Russian Tsarist imperialism to underscore Russia’s view that Ukraine was part of its “sphere of interest.” In May 2009, he “gave Russian journalists an unexpected reading tip: the diaries of Anton Denikin, a commander in the White Army, which fought the Bolsheviks after the revolution in 1917,” and a person known for his hatred of so-called “Ukrainian separatism.” Putin referred to Denikin and his attitude toward so-called “Great Russia” and “Little Russia” with great sympathy and emphasized “that no one should be allowed to interfere in relations between us; they have always been the business of Russia itself” (“Moser Language”: 123–179).

At a conference on “The Russian Language on the Boundary of Millennia,” Putin’s then wife Lyudmila declared in her speech:

“The confirmation of the borders of the Russian world is also the assertion and strengthening of Russia’s national interests. The Russian language unifies the people of the Russian world—the aggregate of those who speak and think in that language. The borders of the Russian world extend along the borders of Russian-language usage” (“Gorham”: 28).

In 2006, a certain Innokentiy Andreev wrote an intriguing article tellingly titled “The Russian language as a shield and a sword.” Andreev’s article was published by Russia’s “Political News Agency,” an organization sponsored by the “Institute for National Strategy.”

On 24 March 2011, Viktor Sorokin, Director of the Institute of the CIS Countries, declared that the Russian Federation had spent more than 1.2 million USD for the support of “compatriots” in Ukraine, and as for 2012–2014, Russia planned to spend 46 million USD for supporting 8 million so-called “compatriots” worldwide, with considerable funds allotted to Ukraine.

On 12 February 2011, Russian sponsors, including the organization “Rossotrudnichestvo,” decided that all Russian funding for “compatriots” in Ukraine would be distributed via the “All-Ukrainian Coordination Council of the Organizations of Russian compatriots.” This organization, which serves as an umbrella for several others, was headed by Vadym Kolesnichenko (on Kolesnichenko see below) (for all examples see “Moser Language”: 162–180).

Kremlin adviser Anatoliy Vasserman, a native of Ukrainian Odesa who now lives in the Russian Federation, represents one of the political think tanks that have contributed to the radicalization of public discussions on Ukrainian national identity and the essence of the Ukrainian language over the past few years. Back in March 2009, Vasserman announced that Ukraine’s integration into Russia in the near future was inevitable; he argued that all those who oppose this process were directly financed by Washington. Vasserman went on to declare that the allegedly uncompetitive Ukrainian language is doomed to die out soon for the simple reason that it is merely a dialect of Russian. He also added various pseudo-linguistic arguments:

“In Ukraine there is massive propaganda for monolingualism motivated by the fact that under the conditions of genuine competition with Russian, the Ukrainian language will sooner or later disappear. […] In spite of the long-term efforts of linguists, the fact that Ukrainian is not a separate language but a dialect can be proven quite easily. They have been trying to change the vocabulary quite radically because this is not difficult to do. They just took all the dialects that existed in the south of Rus’ and found in them words that differ from the literary norm. If they found at least one word that differed from Russian in its meaning they declared it Ukrainian” (cited after “Moser Language”: 175).

Vasserman tried to explain that similar measures of distancing the language from Russian could not be applied in the sphere of Ukrainian syntax, which, in his view, is basically identical with Russian syntax. His statements have of course nothing to do with Slavic linguistics, but are merely a manifestation of his activities as a “political technologist” (“Moser Language”: 174–176).

Language is not the only important part of Russia’s national strategy; there is also history and memory politics. The Russian Orthodox Church, particularly Patriarch Kirill, has been taking an active part (“Moser Language”: 135–161). Even the Holocaust has been utilized in Putin’s propaganda machinery (see “Moser Languages”: 147–155).

By 2008, the dangers of the Kremlin’s strategy became evident when in a nationwide poll to name Russia’s greatest historical figure (with “more than 5 million votes [registered] by telephone, text and the internet”), “Stalin had led the poll early on and narrowly missed the top spot” (“Parfitt”). During a TV show on this theme, Stalin was presented to the audience by Valentin Varennikov, an army general, who said: “We became a great country because we were led by Stalin” (ibid.). Varennikov was a member of a historical truth commission that was established by then Russian President Dmitriy Medvedev (“Moser Language”: 153).

Official Russia has continued its tradition of attempting to depict Ukraine as a cradle of disorder and chaos. At the same time, it has never ceased to send out signals that it regards Ukraine as part of Russkiy Mir, as part of its “sphere of interest,” and not as a state in its own right (“Moser Language”: 153–155).

Over the past two decades, Vladimir Putin and his allies have repeatedly referred to the Russian population of Ukraine as a population of about 17 million instead of 17% (“Diachenko”). In May 2010, Konstantin Zatulin, First Deputy Chairman of the Committee of the State Duma for the CIS and Relations with Russian Nationals Abroad, declared on TV that “Ukrainians are Russians living at the periphery,”, and in June 2010, the Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of the Russian Federation in Ukraine Mikhail Zurabov declared he is “deeply convinced that Ukrainians are not only a fraternal] people to the Russians [“rossiyanam”],” but that he “believe[d] we represent one single people with its nuances and particularities” (“Moser Language”: 171).

After the successful Ukrainian revolution of late 2013 and early 2014, the Russian propaganda machinery headed by Vladimir Putin intensified its attacks against the rise of a new Ukraine in an increasingly aggressive way.

Not only did the Kremlin spread totally unfounded rumors about “pogroms” against the Jewish population of Ukraine; but, on 23 February 2014, after the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) abolished the Ukrainian language law of 2012 by 232 out of 334 votes (“Ukraine abolishes”), Russian propagandists have also claimed incorrectly that the Russian language was ousted from Ukraine, and the Russian population, usually labelled as Russian “compatriots” (“sootechestvenniki”), were under serious threat.

On 1 March 2014, Putin asked “the Federation Council—the upper chamber of Russia’s dummy parliament—to authorize the use of force not just in Crimea, but “on Ukraine’s territory until the socio-political situation is normalized” (“Ioffe”). This is how Julia Ioffe described these events:

Today’s meeting of the Federation Council was an incredible sight to behold. Man after Soviet-looking man mounted the podium to deliver a short diatribe against…you name it. Against Ukrainian fascism, against Swedes, and, most of all, against America. One would think that it wasn’t the illegitimate government in Kiev occupying Russian Crimea—which, lordy lord, if we’re going to get ethnic, let’s recall who originally lived there [the Crimean Tatars, M.M.]—but the 82nd Airborne. The vice speaker of the Council even demanded recalling the Russian ambassador to Washington. America was amazingly, fantastically behind events in Kiev and proved utterly inept at influencing them, and yet none of that seemed to matter. America, the old foe, was everywhere, its fat capitalist fingers in every Slavic pie. Watching the Federation Council, where few of the speakers seemed to be under the age of 60, I couldn’t escape the feeling that this was an opportunity for Russia not just to take back some land it’s long considered its rightful own, but to settle all scores and to tie up all loose ends. You know, while they’re at it (“Ioffe”).

Even prior to that, Russian troops were concentrated in the regions bordering Ukraine, while unidentified armed troops appeared in the Crimea in ever growing numbers. The whole world knew that these were Russian troops, but Russian officials would deny that, while they implicitly admitted it in many of their statements. At a certain point, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov actually argued that Russia’s aggression merely served the protection of human rights. At the same time, citizens of the Russian Federation appeared on the streets of Kharkiv, Donetsk and other cities of Ukraine. The Russian flag was flown on Kharkiv’s central square by a man who has presented himself as an admirer of Adolf Hitler on the Internet (“Shynkarenko”). Also, the leader of the mob that tried to occupy the Regional State Council in Donetsk was revealed to be a former neo Nazi (“Gubarev”). By that moment at the latest, it had become clear that the label of “compatriots” was dangerously close to the Nazi term “Volksgenossen”; that the alleged anti-fascists were in fact the fascists (on contemporary Russian “antifascism” see “Moser Language”: 123–210).

2. The truth about languages and language legislation in Ukraine

Contrary to widespread beliefs, Ukraine is not a bilingual state inhabited by two ethnic groups. It is not a monolingual or multi-ethnic state either. Ukraine, like many other countries of the world, including the Russian Federation, is a multi-ethnic and multilingual country.

According to the most recent Ukrainian population census of 2001, “ethnic Ukrainians make up 77.8% of the population,” while the by far largest minority of the country are ethnic Russians (17.3%). Other ethnic groups are small: Belarusians (0.6%), Moldovans (0.5%), Crimean Tatars (0.5%), Bulgarians (0.4%), Hungarians (0.3%), Romanians (0.3%), Poles (0.3%), Jews (0.2%), Armenians (0.2%), Greeks (0.2%), Tatars (0.2%), etc. (see “Opinion”). Ukraine is thus in fact a multi-ethnic state” (ibid.), but this multi-ethnicity is admittedly of a quite specific nature: not only owing to the large percentage of Russians, but also due to the fact that Ukraine is officially considered home to as many as 130 ethnic groups. Notably, the large majority of these groups are made up of dispersed individuals who happened to settle in Ukraine during the Soviet period. Many Ukrainians in fact have multiple ethnic identities, while the censuses offered one nationality option only. Obviously, this is one of the major reasons why the percentages of ethnic groups in Ukraine are somewhat variable and why between the censuses of 1989 and 2001, a considerable increase in the percentage of ethnic Ukrainians (often about 5%) could be observed in most oblasts of the country. The only region of Ukraine where ethnic Russians constitute a majority is the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, with 58.3% as compared to 24.3% Ukrainians and 12.0% Crimean Tatars ( “Moser Language”: 39–70 ).

Otherwise, ethnic Ukrainians constitute a majority even in the most Russified regions of the country, such as Donetsk Oblast (56.9% Ukrainians, 38.2% Russians) or Luhansk Oblast (58.0% Ukrainians, 39.0% Russians). Moreover, relatively large numbers of ethnic Russians live in other oblasts of the south and east of the country. However, they are a clear ethnic minority in all other oblasts, because the rural regions have not been exposed to the same assimilatory pressure as the large cities. All oblasts of Ukraine are thus genuinely Ukrainian ethnic and definitely not Russian ethnic territory. The situation in the Crimea is the result of a long-term genocide of Crimean Tatars, the autochthonous people of the Crimea, which reached its peak during WW II. Regarding the ethnic makeup of Ukraine’s east and south, it should be noted that Ukrainians, especially those in the east and south of the country, were subject to Stalinist genocide as well, during the Great Famine of 1932-1933 (ibid.).

Official statistical data regarding the languages of Ukraine are based on population censuses inquiring the “ridna mova” (roughly: “native language”) of the citizens of Ukraine. As a result of the massive Russification of Ukraine in Tsarist Russia and in the Soviet Union, only 67.5% of the citizens claim Ukrainian to be their “ridna mova,” whilst 29.6% indicate Russian. It is thus obvious that a “considerable number of ethnic Ukrainians and persons belonging to non-Russian minorities have a command of the Russian language and even consider it to be their ‘native language’” (“Opinion”: 4).

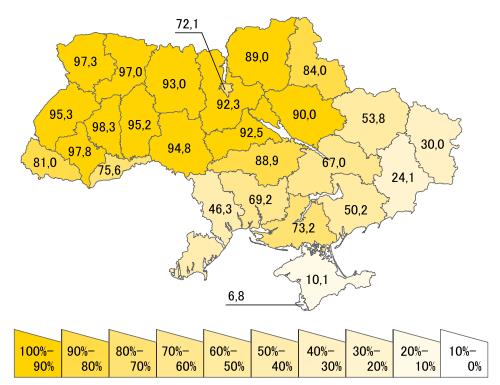

The regional divide is strong.

In Crimea, 77.0% regard Russian as their native language. Crimean Tatar follows second with a percentage of 11.4%, and Ukrainian ranks only third with a percentage of 10.1%. In the following oblasts, fewer than 50% of the population claimed Ukrainian to be native to them in 2001: Donetsk Oblast, Luhansk Oblast, Odesa Oblast. In the following oblasts, only slightly more than half of the population claimed Ukrainian as native: Zaporizhzhya Oblast and Kharkiv Oblast (“Moser Language”: 39–70).

In all other oblasts, the clear majority of the population claims the Ukrainian language as native. In almost all oblasts, the percentage of those who claim Ukrainian as native according to the census of 2001 as compared to 1989, increased, often by about 5% or even more. If the Ukrainian revolution of 2013 and 2014 prevails, the next census will undoubtedly reveal a further increase of these percentages. The Yanukovych regime postponed the upcoming census repeatedly; there are indications that certain political forces wished to prepare the soil for an increase in the percentages of people who would declare a Russian national identity and who would indicate Russian as their native language (“Moser Language”: 281).

Percentage of population with Ukrainian as “ridna mova”

(according to the census of 2001) – Source: “Map 2”

Ukraine is thus not a bilingual state. It is diverse in many respects. Contrary to widespread stereotypes, none of the regions of Ukraine is merely Russian-speaking. This is also true regarding actual language usage. Without doubt, Russian is widely used in some regions, especially in the cities, but this does not make these regions merely Russian-speaking.

In many eastern and southern cities of Ukraine the traditional machinery of Russification is still at work. While Ukrainian is in fact the only state language of Ukraine and the vast majority of Ukrainian speakers knows and actually uses Russian alongside on an everyday basis, discrimination against Ukrainian speakers on the streets of Kharkiv, Donetsk or Odesa on an everyday basis is a widespread phenomenon, as frequently witnessed by myself: Many Russian speakers demonstrate an ironic attitude toward or even contempt of the Ukrainian language, in keeping with traditional Russian views of the Ukrainian language.

Other Russian speakers (not only ethnic Ukrainians), by contrast, openly regret that they had not been given the opportunity to acquire a sufficient command of the Ukrainian language and therefore do not have an active command of a language they truly value. The same is true of many speakers of so-called “Surzhyk” (a very broad spectrum of language varieties that emerged as a result of the mixing of imperial Russian and traditional local Ukrainian dialects), who simply had not been taught the Ukrainian standard language well enough.

3. A brief note on the Hungarians of Transcarpathia

The situation as described above is typical of other minority groups as well. Here are a few personal impressions from a four-day stay in Berehove/Beregszáz in Transcarpathia Oblast in the early spring of 2013.

Owing to the Soviet and Russian imperial past, many representatives of the older generation of Hungarians tend to know Russian rather than Ukrainian in addition to their minority language. Hungarians with a loyal attitude toward the Ukrainian state convincingly explained to me that the Ukrainian state had not yet given sufficient effort to provide the Hungarians of Ukraine with good Ukrainian language teaching in the villages of Transcarpathia. Needless to say, these complaints by no means imply that these Hungarians like to be “Ukrainianized” in the long run. Their criticism simply reflects a very healthy attitude toward their own situation: They desire to retain their Hungarian identity, they wish to be supplied with Hungarian-language media, they want to have their Hungarian schools and they demand for themselves the right to use the Hungarian language in the local administration of Berehove District. At the same time, these Hungarians do request the Ukrainian state to be supplied with good teaching of the Ukrainian language, because they perfectly understand that a command of Hungarian solely is of little use in the state they live in, and the command of another language is generally positive for anyone, including Hungarians.

According to my observations, it is true that other Hungarians of Transcarpathian Oblast, particularly those of the older generation, have not yet developed a positive attitude toward the Ukrainian state and the Ukrainian language either because they stubbornly fail to see that the adoption of a state language certainly does not entail a betrayal of one’s ethnic adherence, or because they are not willing to learn yet another language that is supposedly being “imposed on them,” after they had had to learn Russian in Soviet times.

In fact, Berehove/Beregszáz is a region of Ukraine with a compact Hungarian settlement and with a history that is in a certain way inseparable from the historical Kingdom of Hungary. However, while Hungarian ultra-nationalists—like all ultra-nationalists—do play their dangerous political games with maps of historical Hungary, and while official Hungary has at times complained that the Hungarian minority is not treated well in Ukraine, no one has ever considered liberating Hungarian compatriots and bringing them “heim ins Reich” to date. The fact is very simple: Any politician who has a bit of understanding of his or her responsibility vis-à-vis the citizens of the planet is aware that any aggressive questioning of contemporary state boundaries in Europe equals to playing with fire. Once started, this dangerous game would lead to endless discussions of almost any European state boundary that can ultimately be solved by one instrument only: war.

4. Myths and the truth

The currently widespread claim that the Russian population or the Russian speakers of Ukraine suffer discrimination is a myth resulting from Russia’s propaganda. In fact, the Russian language predominates in many areas of the communicational space of Ukraine. Only in the educational sphere has Ukrainian made great progress during the past years. However, a large number of Russian-language schools do exist in Ukraine, again depending on the region.

Contrary to widespread myths, Russian has thus never been ousted from the schools of Ukraine. Even Iryna Zaitseva, one of the main spokespersons condemning what she terms “forceful Ukrainianization” under President Viktor Yushchenko and Head of the Ukrainian Center for the Assessment of the Quality of Education under Viktor Yanukovych, admitted in May 2010, while promoting Russian as the language of instruction in Ukraine:

“Russian remains one of the main languages used for instruction in schools: 22.4% of the pupils, i.e., more than the ethnic share of Russians in Ukraine, are being instructed in that language (cited after “Moser Languages”: 53).

The regional divide is strong: On the entire Crimean peninsula, even throughout the “Orange” years of so-called forcible Ukrainianization, there were only seven schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction. The demand for the only Ukrainophone school in the city of Simferopol is purportedly so strong that parents line up every year to have their children educated there. Moreover, in practice, the broad use of Russian in “Ukrainophone” preschools and “Ukrainophone” universities was and still is a “mass phenomenon” (“Stanovyshche”).

International organizations have repeatedly confirmed that Ukraine is not a country with widespread xenophobia or extremism (see the examples in “Moser Language Policy”), as has been repeatedly alleged by Putin’s men in Ukraine, particularly Vadym Kolesnichenko. Other organizations monitoring language and minority rights in various countries confirmed that the Russian language is without any doubt sufficiently protected in Ukraine, notwithstanding some minor criticism regarding the educational sphere (“Moser Language Policy”: 36).

Notably, these assessments were given even before the same Vadym Kolesnichenko, together with Serhii Kivalov, authored the highly problematic language law that was adopted in an evidently unconstitutional manner in August 2012 (“Moser Language Policy”: 297–412). Serhii Kivalov is well known for playing a leading role in the election fraud of 2004 (he was head of the Central Election Commission), which led to the so-called “Orange Revolution.” Vadym Kolesnichenko is Moscow’s man in Ukraine. Kolesnichenko has been disseminating Moscow’s current discourse on Ukraine for years. On the one hand, he has presented himself as a human rights activist. On the other hand, he has repeatedly demonstrated that his political views are in fact totalitarian and extremist. A master of Stalinist rhetoric, Kolesnichenko once advised peaceful protesters during the early years of Viktor Yanukovych’s presidency to be careful “not to burn themselves in the fire where they want to warm their hands,” as they would be “pushed under the butcher’s ax, under the ax of the law like cannon fodder” (in Russian, cannon fodder is, literally, pushechnoe miaso ‘cannon meat’), and he labeled the peaceful protesters as “extremists” who should be kept “in the appropriate places of isolation” (“Moser Language Policy”: 181–210; 291–296).

At a certain point, Kolesnichenko even felt the need to hold a press conference while dressed in a uniform of a Second World War Soviet officer. At the same time, he is the co-author of the infamous law of 16 January 2014 that simply copied Russian legislation against so-called extremists, i.e., dissidents, and western NGO organizations, which would henceforth have to be registered as “foreign agents” (“Moser Tradicionnyi”).

It was precisely in the aftermath of the adoption of the law of 16 January 2014 that the Maidan radicalized. A few days later, the regime killed the first three activists and presented itself as a government that did not refrain from beating naked people in the cold, abducting hospitalized protesters to torture them, etc. (ibid.)

After the victory of the Ukrainian revolution, the new government made a serious mistake when it dismissed the language law of 2012 without conveying clearly enough that the Russian language remains sufficiently protected in Ukraine even without the unnecessary law of 2012, and that an entirely new language law was in any event necessary in the long run because—once again—the law had been adopted in an evidently unconstitutional manner (“Moser Language”; on the effects of the law since 2012 see “Dzhygyr”). After that mistake, the new Ukrainian leadership unfortunately made it even worse when it did not manage to convey clearly enough to the international community that the problematic language law of 2012 is in fact still in force even today, because interim President of Ukraine Oleksandr Turchynov vetoed the abolishment of the law on 1 March 2014, instead wisely creating a working group to develop an entirely new language law (“Turchynov poobicjav”). This new law will undoubtedly pay due respect to the needs of the speakers of Russian, who have greatly contributed to the success of the Ukrainian revolution, and to the speakers of all regional and minority languages of Ukraine. At the same time, the law will have to contribute to the further dissemination of the state language all across the regions of Ukraine.

5. Russian propagandistic interpretations of the events in Ukraine between November 2013 and March 2014

The Kremlin and its complex PR network had apparently obtained leadership in opinion making by those decisive days of late February and early March 2013. The media and even some ill-informed scholars, who had not ceased to look at all things Ukrainian from a Russian point of view and obviously depended on Russian media, unanimously deplored the fact that “the Russian language has been banned in Ukraine,” “Russian has been dismissed as the second state language of Ukraine,” etc. The combination of ignorance and self-righteous accusations against “Ukrainian nationalists” in the western media ultimately turned out to be more than annoying; it had become dangerous.

The international community apparently believed Putin’s propaganda and reiterated the stereotypes of violent right anti-Semitic and anti-Russian extremists dominating the Maidan, at a time when ethnic Russians and Jews etc. were brutally beaten and killed alongside ethnic Ukrainians by a regime that did so following repeated appeals from Moscow (“Moser Tradicionnyi”). While the Kremlin repeatedly summoned “the West” not to interfere in Ukraine, its speakers asserted that the “right extremist movement” on the Maidan was sponsored by America and the NATO, and the new government was made up of radicals with whom Moscow would never negotiate.

The Kremlin had gone to great lengths to create a complex propagandistic network that suggested only one conclusion: President Putin was laying down the groundwork to protect the right of Russians and Russian speakers in Ukraine—to protect the so-called “Russian World” (on the “Russian World” or “Russkiy Mir” see “Moser Languages”: 123–179).

6. The Ukrainian population of the Russian Federation

In those days of late 2013 and early 2014, none of the opinion makers raised questions about Russia’s second largest ethnic minority (following the Tatars); nobody asked how Russia treats the Ukrainians in the Russian Federation:

What one should keep in mind is the fact that the Soviet census of 1926 registered no less than 7.87 million Ukrainians living in the RSFSR, in other words 29.7 percent of all non-Russians living in the republic or, “if one excludes autonomous republics and oblasts, Ukrainians made up 53.1 percent of all non-Russians living in the Russian regions of the RSFSR”; moreover, “67 percent of RSFSR Ukrainians reported Ukrainian as their native language” (“Martin”: 282–283). Ukrainians were not simply a dispersed minority. They had compact Ukrainian settlements in the adjacent southern Kursk and Voronezh regions as well as in Kuban. […]). Although Russian Soviet authorities often tended to be reluctant to grant national rights to the Ukrainians of the RSFSR, by 1927 there were 590 Ukrainian-language schools in the republic (ibid.: 284) (“Moser Language”: 123).

Following the Stalinist terror of the 1930s and decade-long massive assimilation, the situation of the Ukrainians of the Russian Federation is quite different:

According to the Russian census of 2002, ethnic Russians made up 79.8% of the population of the Russian Federation, with a percentage quite close to that of Ukrainians in Ukraine. Ukrainians, following Tatars as the largest minority of the Russian Federation (3.8%), constituted 2% of the population, i.e., no less than 2.9 million, with 1.8 million among them claiming Ukrainian as their native language in 2002. Eight years later, the preliminary results of the census of 2010 revealed only 1.93 million Ukrainians in the Russian Federation, namely 1.4% of the whole population. Ukrainians still ranked third after Russians with 80.9% and Tatars with 3.87%, but were already quite close to Chechens with 1.04% and Chuvashs with 1.05% ([…]. On the entire territory of the Russian Federation, 1.13 million census respondents claimed they had a command of the Ukrainian language, in other words 0.82% of the entire population (99.41% Russian, 3.09% Tatar) […]. Evidently, the tremendous decrease of the Ukrainian population in the Russian Federation from 2.9 million to 1.93 million within eight years was not the result of any mass migration. The most likely explanation was that aside from ongoing assimilation, many of those who did not hesitate to freely identify as Ukrainians in former times preferred no longer to do so (“Moser Language”: 124).

The “Opinion on the Russian Federation” as offered by the Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (of the Council of Europe) was approved on 24 November 2011 and published on 25 July 2012 (“Advisory”). The most alarming articles of the “Opinion” concern a significant increase in racism against people “originating from the Caucasus and Central Asia, as well as Roma” and “an increasing use of xenophobic and racist rhetoric by politicians” (ibid., article 15, etc.; original in English).

A particularly interesting finding of the Advisory Committee, in light of the below-described actions against allegedly “extremist” Ukrainian minority organizations in the Russian Federation as well as numerous official Russian statements on the “extremist” suppression of the Russian language, in Ukraine is the following:

132. The Advisory Committee notes with concern that the legislation on countering and prosecuting extremism continues to be sometimes used against persons or organisations engaged in minority protection, and “non-traditional” Muslim groups. Minority representatives have in particular informed the Advisory Committee that, when voicing concerns about the protection of human and minority rights, they are sometimes accused of being “traitors,” “extremists” and threatened with prosecution under the legislation against extremist activities (see also remarks on Article 6 above). Some representatives, involved in human and minority rights, have also allegedly been accused of “inciting social hatred,” and consequently prevented from continuing their activities. Therefore, the Advisory Committee welcomes the decision of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of 2011 providing guidance concerning prosecution for “extremism” and indicating inter alia that criticising politicians and political organisations must not be considered as incitement to hatred (ibid.).

In November 2011, the Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities stated unequivocally:

28. When acceding to the Council of Europe, the Russian Federation committed itself to signing and ratifying the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages by 28 February 1998. It signed the Charter on 10 May 2001, and, from 2009 to 2011, implemented a Joint Programme related to the development of minority languages and cultures in co-operation with the Council of Europe and the European Union. However, no progress has been made as regards the ratification of this instrument (“Advisory”; original in English).

Here is a brief summary of the situation of the Ukrainian minority in the Russian Federation:

The situation of the Ukrainian minority in the Russian Federation differs significantly from that of the Russian minority in Ukraine in many respects. Not only has the protection of the Ukrainian minority in the Russian Federation been extremely weak, but minority organizations have even come under massive attack.

In some respect, Ukrainians are even worse off than many other minorities in Russia. The Russian Federation does not sponsor any Ukrainophone print media, TV or radio programs […].

Moreover, in the entire Russian Federation, there is not one single public school or preschool with Ukrainian as the language of instruction. According to the Union of Ukrainians in Russia, no more than 205 children learned the Ukrainian language as a subject in 2009 in the Russian Federation, and 100 more did so on an optional basis. […]

Representatives of official Russia have frequently argued that Ukrainian schools were simply not needed in the Russian Federation. In 2009 Andrey Nesterenko offered a particularly interesting argument in that regard: According to him, Ukrainian schools were simply unnecessary in Russia “owing to the closeness of the East Slavic languages, the common history (Kyivan Rus´, the Muscovite state, the Russian Empire, the USSR), and the common Orthodox Christian faith” […]. As one might expect, this statement prompted the Organization of Ukrainians in Russia to point out that precisely the same arguments would apply, vice versa, to Russian schools in Ukraine. In reality, however, Russian and Ukrainian were again merely treated as languages with unequal rights (“Moser Languages”: 130–131).

By February 2011, almost all former Ukrainian Sunday schools in Russia were closed, including those in St. Petersburg, Voronezh, Tyumen Oblast and the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous District. On the entire territory of the Russian Federation, there is not a single Ukrainophone school. All that exists are some isolated schools with the Ukrainian language as a subject at the elementary level (“Moser Language”: 131–132).

A special unit of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs for “the fight against extremism” repeatedly organized raids against the only Ukrainian library in the Russian Federation. The library’s director was physically beaten (“Moser Language”: 132). Moreover,

Ukrainian minority organizations in the Russian Federation have been under constant and severe attack during the past few years. A court in Moscow decided in October 2009 that the “Federal National Cultural Autonomy ‘Ukrainians of Russia’” which had been in existence since 27 March 1998 was to cease its activities because it had allegedly not held its assembly according to the rules, had organized a conference in Moscow on “Ukrainian studies in Russia” and commemorated Ukraine’s famine of 1932–33. […]

On 24 November 2010, Russia’s High Court upheld the liquidation of the “Federal National-Cultural Autonomy ‘Ukrainians of Russia’” which had been decided on 27 January of the same year (other Federal National-Cultural Autonomies of the Russian Federation continued to exist). Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov explained that the organization was dissolved “because the chairmanship of this organization did not work to solve issues of culture and education and implement suitable projects, as declared in its statute, but carried out political activities that were directly and openly directed at undermining our bilateral relations” […] One year later, on 29 February 2012, the Ukrainians of Russia organized a founding conference for a new Federal Ukrainian National Cultural Autonomy in Moscow that apparently better suited official Russia. […]

In addition to the Federal National Cultural Autonomy, the “Organization of Ukrainians in Russia” was forced to discontinue its activities beginning in 2009 as well. Allegedly, it had violated Russian laws and its own statute. […] In the fall of 2011, the organization was ultimately liquidated. […].

For the most part, the international community remained silent regarding these events. After OSCE High Commissioner Knut Vollebaek visited Russia in 2009, he was supposed to present his report and recommendations to representatives of the Russian and Ukrainian governments in November 2010. However, the meeting never took place, because the Russian Federation refused to participate from the outset (“Moser Language”: 133–134).

7. Continuing propaganda in 2013-2014

The Russian war against Ukraine was founded on continuing propaganda.

Allegedly, Russian troops were concentrated all along the border regions only by chance—allegedly this was just a military exercise. Allegedly, the heavily armed soldiers with Russian equipment in uniforms without plates that were dispatched all over the Crimean peninsula (the “green men”) were just local self-defense forces. Allegedly, the “Russian” population of Kharkiv, Donetsk, and other Ukrainian cities were crying for Russian help. Coincidentally, the same faces of women in tears who allegedly desperately suffered from the suppression of Russians in Ukraine repeatedly appeared on the screens in different videos, while no observer could even see the slightest sign of pressure exerted on Russians or speakers of Russian.

There was war and there “was no war” at the same time, before and even after the Federal Council of the State Duma of the Russian Federation empowered Vladimir Putin to declare war on Ukraine.

8. Conclusion

A large segment of the international community continues to buy the Kremlin’s propaganda, including politicians, members of the press, and other opinion makers. Some have even been revealed to be on the Kremlin’s payroll (“Shekhovtsov”).

It is stunning that only a comparatively small group of international intellectuals has raised the most important questions of the day: Considering the alarming historical parallels, particularly Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 in the name of “the liberation of the oppressed ‘Volksgenossen,’”—can the international community accept it if a state, based on the evidently dangerous ideologies of “Russkij Mir” and “Eurasianism” (see the brilliant article by Robert Zubrin; “Zubrin”), annexes territories of a neighboring country allegedly to protect its “compatriots”? If the Crimea that is definitely not an “ancient Russian land” really becomes part of the Russian Federation or some kind of Russian protectorate—what will follow: the whole of Ukraine, just like Bohemia and Moravia in 1939? And what might be the next step, given the Kremlin’s ideological foundations?

Michael Moser is Professor of Slavic linguistics and philology at the University of Vienna, at Pázmány Péter Catholic University in Budapest/Piliscsaba, and at the Ukrainian Free University in Munich.

Cited sources

“Advisory.” Council of Europe. Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Third Opinion on the Russian Federation adopted on 24-11-2011. Published on 25-07-2012. Accessed on 27-10-2012.

http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/minorities/3_fcnmdocs/PDF_3rd_OP_RussianFederation_en.pdf.

“Diachenko.” Сергій Дяченко, Українська мова перебуває в нормальному процесі „вирівнювання ситуації“. 03-11-2008.

http://www.razumkov.org.ua/ukr/article.php/expert.php?news_id=863.

“Dzhygyr.” Yuriy Dzhygyr. What is the “Law on Languages” and why it is a problem? (Briefing for English-speaking friends). 08-03-2014.

http://euromaidanpr.wordpress.com/2014/03/08/what-is-the-law-on-languages-and-why-it-is-a-problem-briefing-for-english-speaking-friends/ .

“Gorham.” Michael Gorham. Virtual Rusophonia: Language Policy as “Soft Power” in the New Media Age. Digital icons. Studies in Russian, Eurasian and Central European New Media. Nr. 5 (2011): 23–48.

http://www.digitalicons.org/issue05/files/2011/05/Gorham-5.2.pdf.

“Gubarev.” Губарев – нацист, фашист РНЕ. 08-03-2014.

http://www.rubezhnoye.org.ua/1150-gubarev-nacist-fashist-rne.html.

“Ioffe.” Julia Ioffe. Putin’s War in Crimea Could Soon Spread to Eastern Ukraine And nobody—not the U.S., not NATO—can stop him. 01-03-2014.

http://www.newrepublic.com/article/116810/putin-declares-war-ukraine-and-us-or-nato-wont-do-much.

“Martin.” Terry Martin. The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union 1923-1939. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

“Moser Gaskrisendiskurs.” Michael Moser. Russischer Gaskrisendiskurs – Vladimir Putins Pressekonferenz vom 8. Januar 2009. Studia Slavica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 54/2, 2009: 271–315.

“Moser Language.” Michael Moser. Language Policy and the Discourse on Languages in Ukraine under President Viktor Yanukovych (25 February 2010–28 October 2012). (Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society, vol. 122). Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag 2013.

“Moser Tradicionnyi.” Михаель Мозер. Традиционный абсурд – российские призывы к невмешательству. In: historians.in.ua. 06-02-2014.

http://historians.in.ua/index.php/dyskusiya/1036-mykhael-mozer-vena-miunkhen-pylyshchaba-tradytsyonnyi-absurd-rossyiskye-pryzyvy-k-nevmeshatelstvu

“Opinion.” European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission). Opinion on the Draft Law on Languages in Ukraine. Adopted by the Venice Com-mission at its 86th Plenary Session (25-26 March 2011). Opinion no. 605/2010. CDL-AD(2011)008. On the basis of comments by Mr Sergio Bartole (Substitute Member, Italy), Mr Jan Velaers (Member, Belgium), Mr Marcus Galdia (DGHL Expert). Strasbourg. 30-03-2011.

www.venice.coe.int.

“Parfitt.” Tom Parfitt. Medieval warrior overcomes Stalin in poll to name greatest Russian. 29-12-2008.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/dec/29/stalin-name-of-russia.

“Shekhovtsov.” Pro-Russian network behind the anti-Ukrainian defamation campaign. 03-02-2014.

https://www.kyivpost.com/opinion/op-ed/anton-shekhovtsov-pro-russian-network-behind-the-anti-ukrainian-defamation-campaign-336172.html.

“Shynkareno.” Oleg Shynkarenko. Putin’s Crimea Propaganda Machine. Anton Shekhovtsov’s blog. 03-02-2014.

http://anton-shekhovtsov.blogspot.de/2014/02/pro-russian-network-behind-anti.html.

“Stanovyshche.” Становище української мови в Україні в 2011 році. Аналітичний огляд. 09-11-2011. Рух добровольців «Простір свободи». www.dobrovol.org. Сприяння: Інтернет-видання «Тексти». www.texty.org.ua.

“Turchynov poobicjav”. Турчинов пообіцяв поки не відміняти закон про мови нацменшин. 03-03- 2014.

http://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2014/03/3/7017381/

“Ukraine abolishes.” Ukraine abolishes law on languages of minorities, including Russian. 23-02-2014. Interfax.http://rbth.com/news/2014/02/23/ukraine_abolishes_law_on_languages_of_minorities_including_russian_34486.html.

“Zubrin.” Robert Zubrin. The Eurasianist Threat. Putin’s ambitions extend far beyond Ukraine. 03-03- 2014.

http://www.nationalreview.com/article/372353/eurasianist-threat-robert-zubrin.