The form they work with is moving images, which bridges the gap between art, cinema, and painting. Their method involves exploring the intersection between documentary and artistic elements, questioning the past and present understanding of political life, recurring history, faith, and social context.

Some examples include their project "Theater of Hopes and Expectations" with the Prykarpattia Theater, which, in collaboration with the volunteer initiative "Left Bank," rebuilds a family's home in Kyiv region.

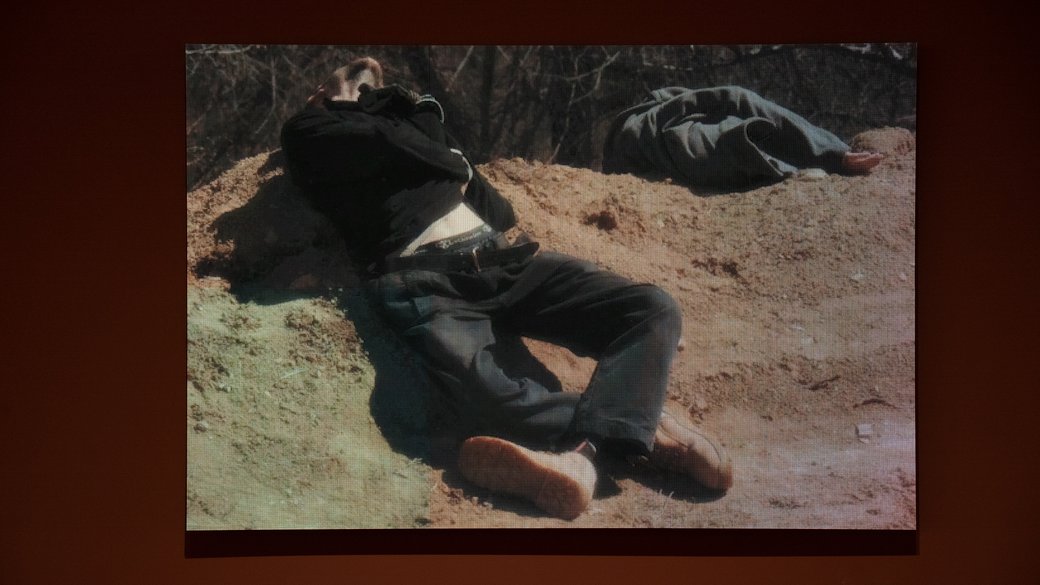

Another significant work is the video titled "Traveler," displayed at the exhibition "Who are you like? Exhibition and Discussion" at the Ukrainian House, which provoked the most misunderstandings, doubts, and even prejudices among viewers. On multiple screens, different fragments of a mountainous landscape panorama were shown, with strange perspectives of human figures. Occasionally, the frozen figures in whimsical poses would move or rise, adjust the camera, and assume another whimsical pose on the ground among the rocks. The performers in this video were the artists themselves, and the work aimed to criticize European pacifism and Russophilia.

Curator and art historian Halyna Hleba spoke with the artists about how to address war in art, the intersection of documentary and artistic elements, violence, and the role of art in intellectual debates in the West.

Halyna Hleba: Please tell us about the context and idea behind the creation of the work “Traveler.” How was it done?

Roman Khimey: Essentially, it's a moving tableau vivant (a type of pantomime where people pose to imitate famous works of art or imaginary paintings or sculptures — Ed.) because it's hard to call it a film. Or maybe it's a performance, within the lines of which there echoes of something filmlike? The desire to make this gesture arose in the first or second month of the full-scale war. Based on my subjective observations, artists were in a state of collective numbness at that precise moment. Not in literal silence, but rather in the repetition of similar images and forms they conveyed. I observed and felt the delicate naivety of how each one drew those holes in the ground, depicted bodies. We, in fact, also turned to the representation of bodies, but we decided not to reproduce the body of the Ukrainian victim.

Our idea stemmed from a conversation about how often foreigners, due to prolonged psychological manipulations by Russian politics, resort to equating victims and depersonalizing the war. From this viewpoint, Ukrainian civilians and military personnel, along with Russian occupiers, are seen as equal victims of the war in their eyes.

Yarema Malashchuk: For a while, we doubted whether it was worth publishing this work at all. By the end of May 2022, when it was first presented, the visual image was, so to speak, on the edge. Can ambiguities, which often become themes for art, be revealed and concretized? In such turbulent times, such audacity can appear to be a speculative gesture.

But these questions arise again and again, and it becomes clearer that the topic of presenting sensitive content is very extensive and does not have a clear-cut positive or negative, a for or against. Artists working with these questions only concretize an issue that already exists.

Actually, regarding this naturalism and the boundary that triggers viewers the most—not everyone manages to understand whose body is in front of them in this work and why it is sometimes lifeless and sometimes moving. This is what significantly influences the perception of the artwork. The Carpathian landscape as a backdrop also disorients the viewer, as it doesn't resemble the ones recognized from documentation of dead Russian occupiers in liberated territories. These recognition games at the stage of acquainting oneself with the artwork lead the viewer to insidious doubt: "How can dead Russians be in the Carpathians? Are these dead Ukrainians? But if they are Russians, maybe it's about the past, about World War II? But here's a modern laptop nearby, and there were no such technologies back then. What on earth is happening here?!" The viewer's irritation can only be subdued with timely clarification that this work is about Russians, but the intended audience of the artwork is Europeans.

Roman Khimey: We decided to recreate the "poses" in which the bodies of Russian occupiers lay and transfer them against the backdrop of a landscape shot in the spirit of German Romanticism. At that time, social media was full of photographs of dead occupiers. Ukrainians "collecting" such photos at that time can be clearly explained—seeing a photo of a dead occupier meant having hope that you would survive.

We can already see that Ukrainians have formed a kind of new normalcy in their perception of images of death. We no longer shy away from what Europeans have averted their gaze from for too long, fearing it might be misconstrued as a morbid fascination with death. For us, observing dead Russians occasionally serves as a form of therapy, aiding Ukrainian society in confronting its fears. But how do foreigners perceive this work abroad, what do they see in it?

Roman Khimey: I once spoke with a German professor about this work, and he asked: "Well, doesn't this contain a message to the Russians: 'Hey, you stupid Russian soldier, see what will happen to you, get out of this land'?" And I allowed myself to be frank and say that this work directly appeals to him, to the German intellectual. There is no Russian agency or Russians as subjects being addressed in this work.

We address the Western viewer about the need to stop trying to understand this war by analyzing the Russian side. All these "poor Russians," "bad Russians," "good Russians," "lost Russians," and "dead Russians who did wrong by coming here." Europeans endlessly attempt to analyze and understand the place of Russians in this war, while Ukraine and Ukrainians are often not granted the same opportunity. In Westerners’ discussions about the war, we simply lack subjectivity, yet all of it is given to Russians by German intellectuals. And that professor is a vivid example of how Germans even try to find some message or lesson for the Russians here.

So, the people the work is addressed to don't see themselves in it?

Roman Khimey: I observed at exhibitions abroad that when the viewer passes by the artwork, the image triggers them at first because it obviously resembles dead bodies. Visually, they need to engage in complicity. But then the viewer gets a step closer, and the moment comes when they read the title Der Wanderer—The Traveler. Here, their understanding scheme shatters because the traveler is a recognizable homage to the work of Caspar David Friedrich, a kind of icon of German Romanticism for them. And here, the knowledge of the Western viewer about the tragic reinterpretation of German Romanticism by the Nazis comes into play. They consciously or subconsciously understand how the Nazis abused this image of the solitary hero and scaled this solitude of Romanticism to the entire German nation. Therefore, the visual component of our work is easily recognizable to them after reading the title.

Yarema Malashchuk: This also reinforces Europeans' conventional understanding of Europe and Russia as some sort of yin and yang, constantly engaged in a historical-political dialogue. The Germans had German Romanticism, the Russians had their own, and they seemed to reference each other. "Prodigal sons" like dead Russians who also "went astray" resonate with such audiences, the need to explain to them where to go so they return home. All this morality, decadence, humanism, and romanticism intertwine into one complex.

Roman Khimey: It's also worth emphasizing our authorial approach to representing the romantic in the landscape, which refers to Matthew Barney's reflections on the fact that the male figure in Caspar David Friedrich's painting is not an observer but rather a full-fledged overseer or guardian who commands the land, and this can be felt in the position of his body. Such mythology in the paintings of David Friedrich speaks to the desire and ability to dominate. Our artistic gesture is the final part of this colonial mythology, where the body of the colonizer vanishes without a trace in the fields and furrows. The only perpetuation for this body, in this case, is "not forgetting to put sunflower seeds in your pocket."

Continuing Yarema's thought on the historical connection of the ecstatic, Germans and Russians have periodically portrayed each other as both oppressors and educators over the centuries, changing roles depending on political circumstances.

However, if we delve deeper into the decoding of your work, despite the title borrowed from Caspar David Friedrich, in the description of the artwork, you refer to the series Rapid Response Group and their photographic work “If I Were a German,” which is iconic in Ukrainian photography history. Artists Sergey Bratkov, Sergei Solonsky, and Boris Mikhailov, like you, simultaneously acted as authors and performers in the frame. The series questioned the concept of history written by the victor. However, if the Rapid Response Group imagined themselves as Germans living their hypothetical "best life in Kharkiv," you "embody" the image of dead Russians. Does this altered reality hold significance in the series?

Yarema Malashchuk: If we say that the Rapid Response Group changed the Soviet propaganda image of Germans from "bad" to "good," we changed Germans from "good" to "nostalgic for romanticism" or even to "Germans longing for infantile reconciliation."

So, this work critiques the elitist, intellectual Western European viewer who painstakingly attempts to find a compromise between their perceptions of Russian culture, their sympathy for it, and the current reality, forcing them to deconstruct their notions of morality and the constancy of "high culture." In my opinion, it poses a significant challenge to them, one they systematically and consciously resist. By the way, did the work’s title emerge before the concept was formed and developed, or was it decided afterward?

Yarema Malashchuk: There were several title options at different stages. The first title was quite straightforward: "If I Were a German," so it started from there.

Roman Khimey: We chose not to address Germans directly in the title because doing so would make everything too literal, reducing Germans to just a nation or a country. Moreover, we were keen to avoid any perception of our work as undiplomatic attacks against Germany. Our intention was to allow space for interpretation and consideration of other Western countries as well.

Yarema Malashchuk: We settled on "The Wanderer," which refers to German Romanticism. It was essential for us to point out this bitter irony and the substitution of the word "wanderer" with "the little green man on vacation," who "wandered" into Crimea in 2014 and occupied it.

The work "If I Were a German" was an ironic piece by the Rapid Response Group. Created in the 1990s, although after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it was still burdened by the ideologically formed memory of the war that weighed heavily on the authors. Does your work contain a similar grotesqueness?

Roman Khimey: If we joke, it's not with postmodern satire in the spirit of the 1990s, you know, this biting irony with laughter into emptiness.

Another crucial point to consider is that progress made by the Armed Forces of Ukraine has led us to a phase where diplomats, cultural figures, artists, and all of us will have to pick up the conversation about this concept of "Russian Romanticism" in a timely manner. Because we were trained under the pressure of Russia, they forced and imposed their language and culture on us. We know about Russian colonialism better than any French or German curators. And we will need to decipher all this. Not so they talk about themselves and to themselves, but so we talk about them. Because if the Russians themselves do it, they will leave convenient formulations and justifications for themselves. It is crucial for us not to allow these justifications to pass.

This conversation was recorded in June 2023.

Text originally published (in Ukrainian) by Suspilne Kultura as part of a collaboration with Documenting Ukraine.

Translated by Kate Tsurkan