The Chełm-Kyiv train finally crosses the Polish border and stops on Ukrainian territory. The conductor announces that passengers can get off and stand near the train cars. A woman nearby, around 60 years-old, breathes a sigh of relief and says, “Finally home!” She openly shares that she traveled to her daughter in Poland but now lives in Kyiv. She reveals that she herself is from Luhansk, and currently, she has nowhere to return. She confesses that she was very afraid to leave, perhaps even more than of shelling, because who needs her there? “There” is somewhere beyond the borders of her native region.

She explains how it used to be for her: there is a hometown and a native region where everything is familiar and where you feel at home, and then there are cities like Kyiv, Lviv, Ternopil, and others, distant and unfamiliar. Not native. Not home. “But now, everywhere feels like home,” she laughs. And she adds: because of the people.

In the summer of 2021, six months before the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, I traveled to Soledar for the first time to write about the artistic residency organized by the Izoliatsiia Foundation. What did I know about this city? Only that there was the Artemsil company and its incredible salt mines. What did I know about the people who lived there? Nothing at all.

Within a few days, I got to know a writer who led a book club in Soledar, teenagers who set up a rehearsal base by transforming an abandoned utility building on the stadium grounds, and the director and staff of the House of Culture who turned the place into a community cultural center with clubs, concerts, film screenings, various courses, and workshops. I visited a local restaurant, library, and park.

I felt comfortable everywhere—just like at home.

Because of people. Open, curious, ready to share their love for their hometown. I asked them questions, and they asked me more in return. Did I hold any preconceived notions before the trip? Absolutely, though they were probably lurking in my subconscious—I also come across different perspectives on the internet. And two years later, I was already hugging an unfamiliar man at the station who, bewildered, asked me for directions. He had left Soledar along with his mother and they were heading further, beyond the border, because his mother needed special medical care.

He said, “We’re from Soledar. Have you heard of such a city?”

I replied, “I’ve been there, it’s wonderful.”

And then he hugged me. And I burst into tears.

The full-scale invasion brought a lot of pain, including the deep pain of losing one’s home. Along with it came a life of uncertainty, fear, and distrust. People were fleeing from the war and didn’t know whom they would meet at the train stations in other cities. People waiting there didn’t know whom they would meet, but they still prepared sandwiches and carried blankets. Initially, to warm the body, and later—the soul. War intertwined us, drawing us closer together. We inadvertently, and sometimes even unwillingly, got to know others, and therefore ourselves. We defied stereotypes, overcame our fears and prejudices, and became closer. We even came to love the cities that these people were forced to leave and yearn for so much.

When I take my child to a dance class, I always buy coffee at the same kiosk. A woman who came to Kyiv from another town works there. Her husband is at war. We always talk about work, fresh pastries, the weather, but also about the Russian shelling they experienced, along with our hopes and fears.

We have different experiences, but we always have something to talk about. The dance class is led by a young guy from Avdiivka. Once I asked him about his home city, and he briefly replied that he no longer has his home, school, or the stage where he first danced. My child has grown very fond of him because of his use of the Ukrainian language and calm demeanor. There’s also a girl from Mariupol in the same dance class. While waiting for the girls, her mother and I talk about everything under the sun: school, childhood illnesses, weather, books, but also about how Russians are now living in their apartment, how someone from their relatives was “taken to the basement,” how children’s drawings are still on the walls of their old home, but it’s okay, the kids will draw new ones. My relatives are under occupation in Kherson Oblast, and hers are in Mariupol. We talk about the sea that we miss, about Kyiv, which is now home for all of us. We discuss all of this and then go back to talking about something ordinary, laughing a lot.

Shared experience unites us, and different experiences no longer scare us away. We extend our hands to strangers, pulling them out from under the rubble of Russian missiles and airstrikes. We are ready to listen and want to speak. But at the same time, we are also ready to be silent together. We embrace strangers because they have escaped hell, they have lost their homes, and they come from those cities and streets where we once lived or played. Strangers embrace us because we “have also been through it,” because we smiled or cried, offered help, or needed it ourselves. Now when we ask people where they are from, it’s not to slam the door in their faces or blame them for something, as it was ten years ago, but to say: yes, I’ve heard, I know, I’ve been there, I’ve read about it, I’ve seen it, I sympathize…

We mourn for the cities and places where we grew up, where we have been, and even for those we have never been to, which are now occupied or lie on the front lines. We promise ourselves to go to Crimea, Donetsk, and Mariupol after our victory. We cry as we look at photos of cities and towns destroyed by Russia, even though we may not have heard about some of them before.

We study geography by placing points of pain and hope on our shared map. We set photos from Bakhchysarai and the Stanislav Cliffs as our phone or laptop wallpapers, buy scarves with prints of paintings stolen by Russians from the Kherson Art Museum, and wear jewelry inspired by the murals of Polina Raiko’s house destroyed by flooding after the Russians blew up the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station. We attend films about Mariupol, exhibitions about Kherson, buy books about Donetsk and Luhansk. We eat from dishes created by Crimean Tatar craftsmen, order flowers from Kharkiv. We donate our favorite books to libraries in liberated territories.

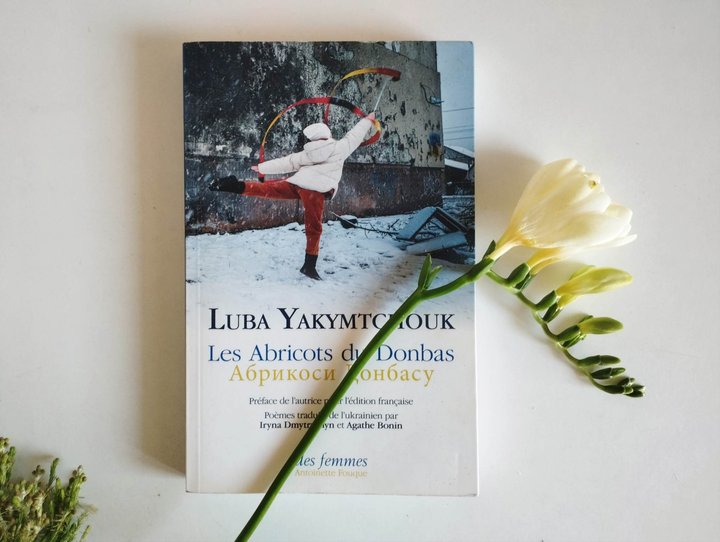

We listen as Lyuba Yakimchuk reads her poetry from the collection Apricots of Donbas. How she reads it at the Grammy Awards ceremony, how actress Catherine Deneuve recites these poems in French. We search for this collection in bookstores. We quickly buy the debut poetry book of Maksym Kryvtsov, who died on the front, and promise ourselves to buy more books and not take living authors for granted.

We attend meetings with writers who travel around Ukraine as part of the Merezhyvo (“Lace”) Project initiated by PEN Ukraine. We collectively buy tens of thousands of copies of Anastasia Levkova’s book There’s Land Behind Perekop because we want to know more about life in Crimea before the annexation. We participate in protests advocating for illegally imprisoned Crimean Tatar activists in Russia because we know something about life on the occupied peninsula. We hear about it not only from the news but also from people we respect, read, and trust.

We do so much, primarily for ourselves, to understand, to come closer, to not be afraid. And it seems that we are gradually succeeding, thanks in part to cultural projects that allow us to comprehend, accept, and understand our diverse life experiences.

...In an empty, semi-dark room stands a small glass table illuminated from below by soft light. On it are all the essentials for tea: various cups and mugs, a sugar bowl, a teapot for brewing, and a large metal kettle for pouring water. We see only the silhouettes of this familiar tableware. Beyond the table, a video is projected onto the entirety of the wall: a river is flowing. All those interested are invited to have tea: please choose a cup for yourself. And only upon approaching the table, you see: it’s not just tableware. Here stands a blackened, burned sugar bowl. Only its lid hints that it once had bright flowers. This sugar bowl is from Chernihiv Oblast. The house it came from no longer exists—only ruins remain. But the sugar bowl is here: please take as much sugar for your tea as you need. There are also cups from Bakhmut, from Kherson Oblast... You grasp the cup of warm tea with both hands, a cup that someone once held in peacetime and then under shelling and explosions. You sip this tea along with tears.

This tea gathering is the artistic project “From the San to Home” by film director Olha Oborina and conceptual artist Nadia Sobko, created at the People’s House in Przemyśl as part of an artistic residency. The tableware was sent to them by people who managed to leave and take their favorite cups with them and volunteers who clear rubble and rebuild houses.

Nadia Sobko, who works with ceramics, shares that she herself is a volunteer who reconstructed houses in Chernihiv Oblast last year along with people from different regions and backgrounds. She describes the remarkable feeling of collectively raising walls for people you didn’t know before but now not only know but love.

Olha Oborina is the main cinematographer of the Ukraїner project. She filmed the flooded areas of Kherson and the liberated regions of Kharkiv. She talks about how people invited them to share meals, how open they were, how they wanted to discuss their experiences, and simply wanted to be listened to. She describes the gratitude they expressed when carolers visited the liberated and war-torn territories.

This tea gathering is perhaps the best metaphor for our lives today. Scorched, damaged, from different cities and with different experiences, we come together to continue doing what we know and love. Ultimately, just to live. Like these cups, which for one evening became ordinary tableware from which people drink tea.

We live amid sirens and shelling. We emerge from shelters and go to theaters, cinemas, exhibitions. We visit bookstores that opened during wartime and search for new books written during this period. If it was once said that culture stitches together regions, today culture not only stitches but also creates new patterns on this map.

We haven’t forgotten about the war; we live with it daily. However, we also reflect on it, talk about it, and seek our place in this new reality. It’s good when we have someone to lean on. Of course, there is division, there is non-acceptance, and there are stereotypes that someone not only doesn’t want to overcome but also reinforces. Some find it easier to blame others. Some find it easier to close themselves off from others. Some don’t need others’ experiences and don’t consider those experiences valuable or worthy of attention. However, these cases should not devalue or negate all the valuable things that we collectively build every day.

...The conductor of the Chełm-Kyiv train peers out of the carriage and shouts, “Hold on to each other, don’t disperse, and don’t get lost; we’re departing soon!” People laugh. Meanwhile, he doesn’t even realize that he has spontaneously formulated a very accurate rule for survival in these challenging times for us. Hold on to each other and don’t get lost.

Text originally published (in Ukrainian) by Suspilne Culture as part of a collaboration with Documenting Ukraine.

Translated by Kate Tsurkan