Democratic Breakdown and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism in Slovakia: Interrelated Trends?

The Slovak Republic is a historically successful example of post-communist transition. The process of democratization in Slovakia began after the fall of communism in 1989, during the period when the Czech Republic and Slovakia formed the Czechoslovak state (1989–1992), and continued and was completed after 1993, when an independent Slovak state was established.

Slovakia’s democratic consolidation however, followed a non-linear path.[1] With Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar’s authoritarian-style administration after 1992, movement towards democratization slowed down, and from 1994–1998, it de facto stopped. With the ousting of Mečiar’s government in 1998 and thanks to the prompt reversal of that government’s authoritarian policies, coupled with effective reform in political and socio-economic areas encouraged by the prospect of joining the EU (EU), Slovakia quickly strengthened its developing democratic institutions, met the criteria for EU membership, and joined the EU and NATO in 2004.

Certainly, Slovakia’s membership in the EU had a stabilizing effect on the country’s democratic institutions and society more broadly. Although EU membership has contributed to sustaining the basic framework of a liberal-democratic government in Slovakia, it has not completely prevented the emergence and promotion of illiberal trends in that country.[2] This can be seen in the strengthening of anti-system movements at the end of the third decade of Slovakia’s democracy, despite the country being a part of the EU. In 2016, this anti-democratic trend resulted in the right-wing extremist party People's Party Our Slovakia (ĽSNS) being elected to the Slovak parliament.

The rise of right-wing extremism in 2016 may appear at first glance to be a temporary deviation from Slovakia’s post-authoritarian democratic consolidation. However, the way in which right-wing extremism emerged in Slovakia, as will be discussed in this paper, support the claim that it was not an accidental or deviant phenomenon, but was related to the declining quality of democracy in the country.

The following pages elaborate on this thesis.

Factors that strengthen right-wing extremism in Slovakia: ethnic politics and social deprivation

Ethnic nationalism was an important factor in Slovakia’s socio-political development after the fall of communism. Prior to independence in 1993, Slovakia was part of a federal state together with the Czech Republic, known as Czechoslovakia. The country’s population was marked by significant ethnic diversity, with minorities constituting up to 15% of the population. This percentage was the highest proportion of minorities among all countries of the Visegrad group. Given these demographics, ethnic nationalism acted in Slovakia as a socio-political factor in two dimensions. Its political proponents – in a milder or in more radical form – began after 1990 to promote the idea of state independence and separation from the Czech Republic, while presenting the idea of the Slovak Republic as an ethnically pure nation state. Defining the Slovak Republic along ethnic rather than more inclusive civic terms would have discriminatory effects on minorities living in the territory, like Hungarians, Roma, and Ruthenians.

The division of Czechoslovakia in 1993 was influenced by a number of factors stemming from the relationship between Czechs and Slovaks. The key point, however, was that the impulse to divide Czechoslovakia came from Slovakia, and various actors of the so-called Slovak national camp took part this process that came to be known as the “Velvet Divorce.” As a result of a unique set of circumstances in 1992, after the second free parliamentary elections, the option of dividing Czechoslovakia into two national republics, initially promoted by a politically marginal group of radical, far-right actors from the very beginning of democratic transition, was eventually realized. The Slovak actors involved in this process had a revisionist profile and demanded that the Slovak Republic be built on the legacy of the “independent” Slovak state that existed during World War II (1939-1945), and was a client state of Nazi Germany.

After the division of Czechoslovakia and the creation of an independent Slovak Republic in 1993, the radical groups that instigated the process failed to enforce their concept of an ethnically “pure” nation-state. Instead, the Slovak Republic claimed its commitment to democratic values, identical to those on which European integration was founded. The new Slovak state embodied a combination of ethnic and civic principles. Radical-nationalist and right-wing extremist forces thus only partially achieved their goals in the first period of political post-communist transition. Indeed, Slovakia established itself as an independent state, but its character differed considerably from the ideas of the right-wing extremists.

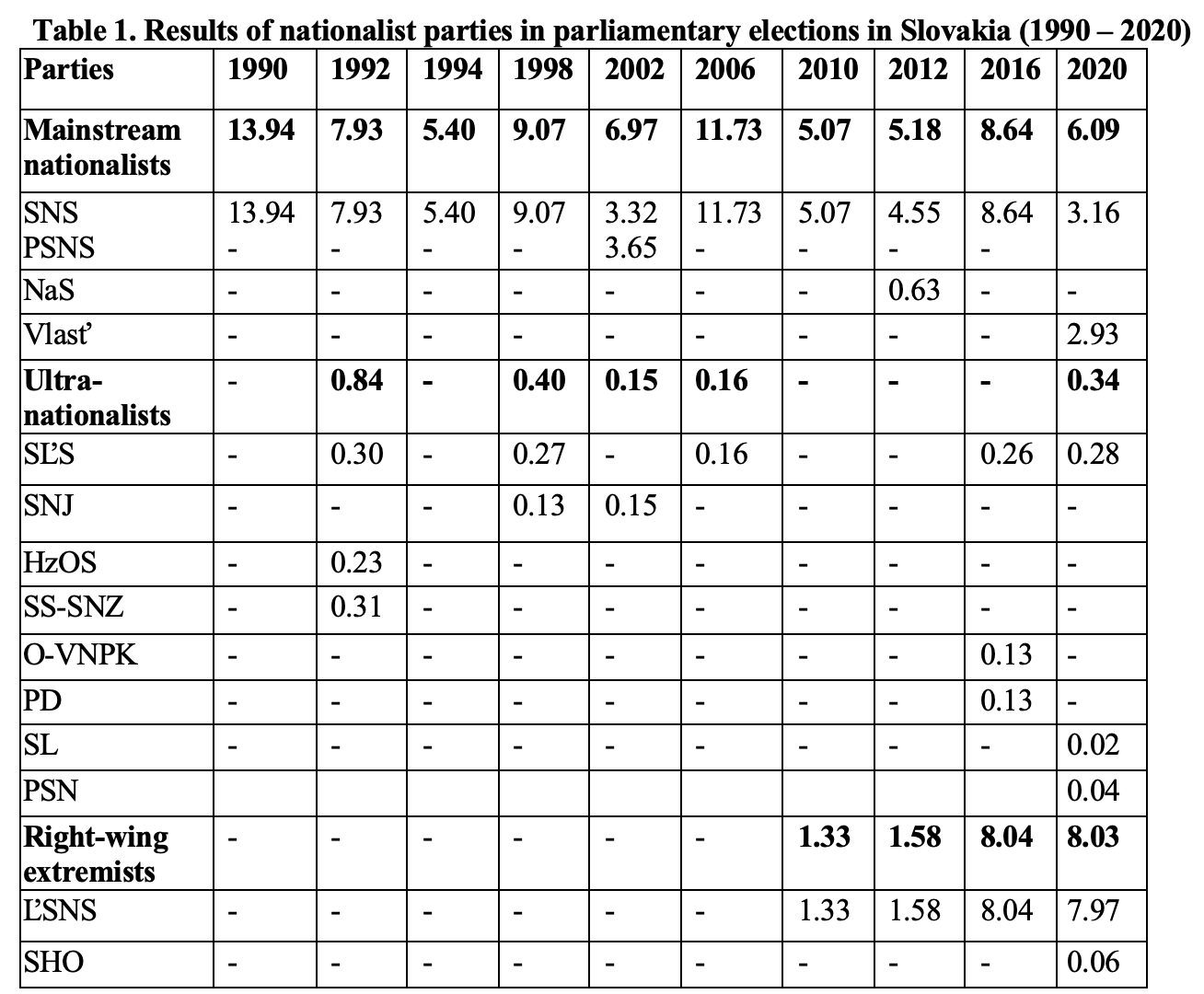

The rise of ethnic nationalism at the beginning of Slovakia’s democratic transition and the maintenance of ethnic politics as a major factor in political development over the next quarter century did not, however, increase the political weight of extremism. Extremist parties initially failed to turn radical ethnic politics (including playing the “anti-minority card” by stirring anti-Hungarian and especially anti-Roma, but also anti-Jewish sentiments) into a decisive factor to gain electoral support needed to become a relevant political actor. As such, radical-nationalist and right-wing extremist forces failed to penetrate mainstream politics, remaining a marginal part of the nationalist camp. Although radical-nationalist political actors repeatedly ran in parliamentary elections, they did not succeed in winning enough votes to gain parliamentary representation from 1990 to 2016. Among the nationalist parties, only the mainstream SNS entered parliament from time to time. In 1992–1993 and 1994–1998, as well as in 2006–2010 and 2016–2020 it formed a part of the ruling coalitions, as a junior partner first to HZDS and later to Smer-SD.

A central part of the societal transformation after 1990 in Slovakia included economic and social reforms. Privatization, de-nationalization, liberalization, decentralization, the opening up to the external economic environment – all of these processes transformed Slovakia into a functioning market economy. The process of marketization, however, did not unfold without problems. Especially in the initial stage, marketization was accompanied by inflation, currency devaluation, and rising unemployment. A large portion of the population fell down the social ladder, and many citizens perceived this movement for the worse. They expressed their dissatisfaction and disappointment, blaming the reform measures for their worsening socio-economic status. As a result, in the ongoing struggle between pro-reform (pro-market) and anti-reform forces, a considerable part of the population joined the opponents of marketization.

This presented an opportunity for extreme right factions in Slovakia. From the very beginning of Slovakia’s democratic transition, the extreme right opposed economic reforms. Radical-nationalist and right-wing extremist groups opposed privatization and liberalization, pointing out that the introduction of market principles “under the patronage” of the West leads to the impoverishment of ordinary citizens. However, anti-capitalist rhetoric and highlighting social deprivation (similar as playing with the card of ethnic politics) did not increase their political weight, as some would have expected. The national-populist “mainstream” parties used the topic of social deprivation much more effectively than the fringe radical nationalists and right-wing extremists did. As a result, the national-populists gained strong electoral support with their social deprivation platform. They dominated the political scene, reached influential positions of power in state institutions and participated in government for longer time than most programmatic parties (in total 18 years since 1990).

Unlike the national-populist faction, right-wing extremists and radical nationalists remained in a marginal position for a long time; for years, they were relegated to the empty space of the party system. In the years 1990–2006, the ultra-nationalist parties (Slovak People’s Party – SĽS, Slovak National Unity – SNJ) tried to get elected into parliament, but they received less than one percent of the vote. With such a low showing in the elections, extremist formations sought to compensate their political irrelevance by actively entering the public discourse. To that end, they exploited topics mostly connected with historic revisionism, like the anniversary of the Nazi-established Slovak state from WWII, the fates of that state’s representatives, including its leader Jozef Tiso. Representatives of right-wing parties organized commemorative public events, at which they presented apologetic views in the spirit of the Nazi ideology of the WWII Slovak state. The influence of these formations on party politics in Slovakia, however, was negligible.

The fundamental change in position of right-wing extremists on political scene occurred in 2016 (See Table 1).

Characteristics of the Slovak right-wing extremist scene

Extremist (anti-system) groups in Slovakia can be described as organisations which, through their programme and activities, question the established democratic system. They directly or indirectly seek to eliminate the liberal democratic government that has existed in Slovakia since 1989. These groups are characterized by a clear rejection of human rights protection. They deny the principle of equality of people, and challenge the basic principles of a market economy. Their political credo is characterized by historical revisionism, anti-Semitism, anti-Roma racism and pan-Slavism. Their foreign policy orientations are marked by resistance to European integration, anti-Americanism, the rejection of NATO, and support for Russia’s foreign policy. This right-wing extremist and radical-nationalist scene in Slovakia consists of various entities, including political parties, non-party associations, unions and initiatives. The most radical elements include aggressive and brutal neo-Nazi groups that are violent towards their ideological opponents and members of minorities, and seek to intimidate the public through hateful messages.

Among the non-party actors of the right-wing extremist scene, the most important entity was for a long time the civic association “Slovak Togetherness” (Slovenská pospolitosť in Slovak, SP) founded in 1995. This organization significantly contributed to the formation of the current form of right-wing extremism in Slovakia. For almost two decades, the SP was considered a symbol of the Slovak right-wing extremist movement in terms of activities, program, rhetoric, organizational base, and until recently even the visual appearance of members who wore at public events uniforms reminiscent of WWII fascist politics.[3] The association’s credo was marked by open opposition to parliamentary democracy as a form of political organization of society, radical nationalism, strong anti-Hungarian rhetoric, and virulent anti-Semitism. The association was built on a strictly centralized and hierarchical “leadership” principle.[4]

In 2003, Marián Kotleba, the radical nationalist and revisionist activist, joined the SP and became the organization’s leader (“vodca”, “führer”). After Kotleba’s entry, a significant activation and direct politicization of SP’s performance took place. At ten years of activity, the SP decided to expand its activities beyond the streets and into the area of party politics. In 2004, SP’s leaders submitted an application to the Ministry of the Interior for the registration of a political party. In January 2005, the Ministry officially registered the SP as a political party called Slovak Togetherness – National Party (Slovenská pospolitosť – Národná strana, SP-NS).

In the course of 2005, the new party organized various public events across the country, where its representatives spread racist messages and provoked clashes with police. In response, the prosecutor general filed a motion with the Supreme Court in October 2005 to dissolve the SP-NS. In March 2006, the Supreme Court dissolved the party. The court concluded that the party’s activities were in conflict with the legislation, because in its programme it called for restriction of the right to vote for certain categories of the population, which violated the principle of citizen equality enshrined in the constitution. Furthermore, the implementation of the SP-NS‘s political program would lead to the establishment of an undemocratic political regime (“corporative state”), similar to the one that existed in Slovakia during WWII; it would, in effect, mean the removal of democracy. The question of why the Ministry of the Interior registered an anti-system and undemocratic party in the first place, however, remains unanswered.

After the dissolution of the SP-NS political party, Slovak Togetherness continued its activities as a civic association under its original name. In 2008, the Ministry of the Interior made a decision to dissolve the organization, but the Supreme Court ultimately annulled this decision due to a formal procedural error made by the Interior Ministry. In 2009, a group of SP’s prominent members led by Kotleba left the organization and began implementing a project to create a new right-wing extremist party – under a different name, but with identical ideological, programmatic, and value characteristics as SP. In the summer of 2009, Kotleba announced that he wanted to establish a new political party called Our Slovakia. The party was established using legal loophole, by taking over the already existing, though irrelevant, Party of Friends of Wine and renaming it twice (first to the People’s Party of Social Solidarity and then to the People’s Party Our Slovakia / ĽSNS). The former SP’s leader Kotleba became the leader of ĽSNS. In terms of ideology and political platform, the ĽSNS followed up on the SP.[5]

Although the anti-establishment rhetoric typical for populist entities was present in ĽSNS’ arsenal from the very beginning, it is not a typical populist party. Rather, it is an anti-system party. In other words, its intention is to replace the existing political system by another one that lacks the basic features of a liberal-democratic regime, free market economy and a culturally, ethnically, and religiously open and diverse society.

After two unsuccessful attempts in the parliamentary elections in 2010 and 2012, ĽSNS finally managed to become a relevant political force in 2016. The party further consolidated its growing position in Slovak politics in the 2020 elections. This raises the question of how a fringe, far-right group managed to gain influence and official representation in Slovak government. For one, state institutions (executive and judicial bodies) failed to use the legal system or the preventative or repressive political tools at their disposal to stifle the emerging extremist scene. The unqualified proposals to cancel registration or to dissolve the extremist parties and overlooking their racist ideology by law enforcement and investigatory organs and courts, created an atmosphere in which the state de facto tolerated the open dissemination of racist ideas and messages of inequality and violence. This atmosphere provided comfortable conditions for right-wing extremist groups to operate, allowing them to openly communicate with sympathizers and publicly disseminate their views that are incompatible with the principles and values of liberal democracy.

Democratic breakdown: manifestations and implications

The character of party competition in Slovakia in the period of democratic transformation

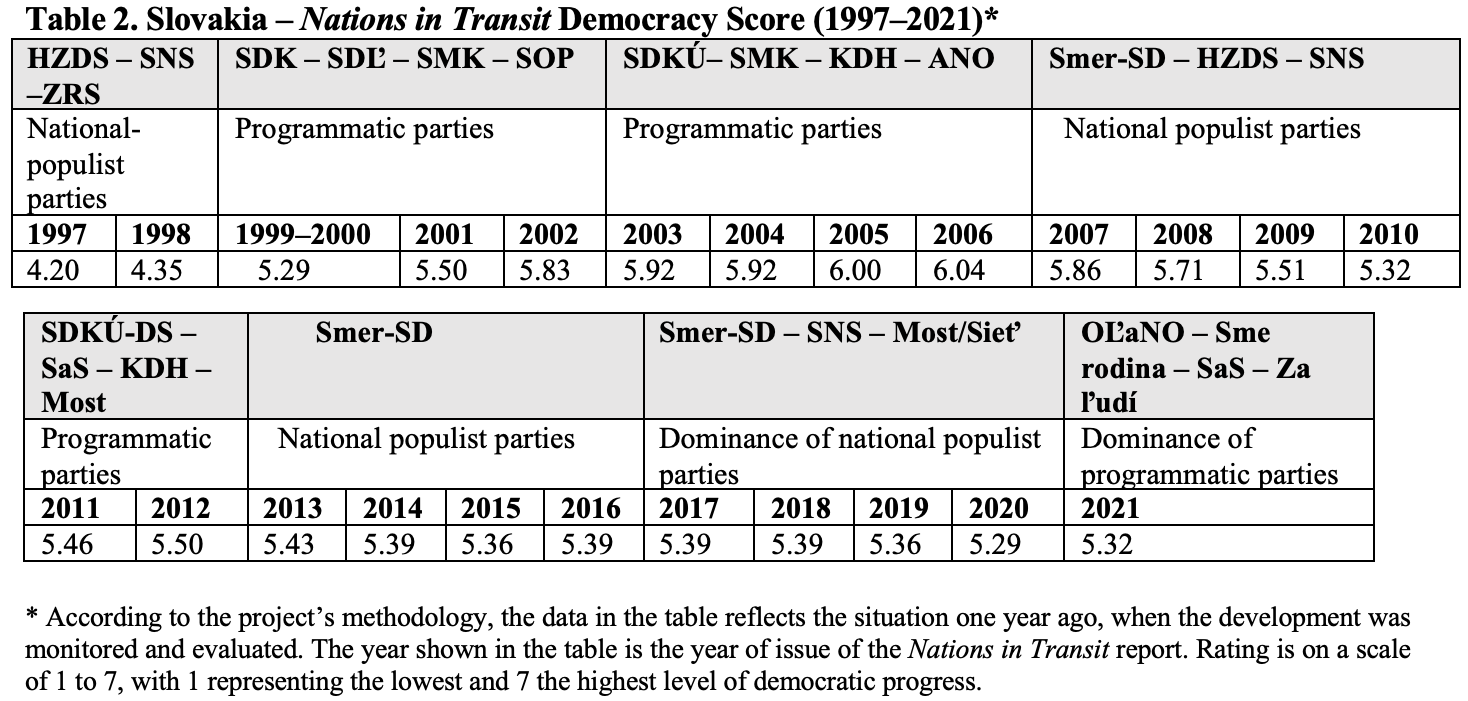

Until 2016, the determining factor configuring the Slovak party system was the competition between two groups of political actors: programmatic and national populist parties. In addition to their different attitudes towards socio-economic reforms and the use of ethnic nationalism, another area in which there was clear divergence between these two political factions was their approach to power execution. In the case of programmatic parties, their approach was in line with the principles of liberal democracy and ensured a standard level of democracy. In the case of national populist parties, their approach to power execution was marked by illiberal practices and manifestations of authoritarianism that included efforts to concentrate power, confrontation with the opposition, civil society and minorities, majority governance syndrome, party political clientelism, violations of the rule of law, and attacks on independent media. The application of such practices in Slovakia has resulted in a repeated regression of democracy, recorded in international comparative studies, including the Freedom House’s Nations in Transit project. Freedom House’s study confirmed that in the periods when national populist parties were in power, the quality of democracy in Slovakia deteriorated or stagnated, while the governance of programmatic parties contributed to democracy’s improvement.

The issue of quality of democracy in different contexts has been getting increased attention among the Slovak scholarly community in recent years. Some experts point out the linkage between prospects for democracy, populism, corruption and extremism, analysing a broader spectrum of relevant areas in which this linkage manifests itself.[6] In this paper, the process of democratic backsliding in Slovakia is examined in the context of its impact on the emergence of anti-system extremists in three areas: 1) the exercise of power and performance of institutions, 2) party politics and electoral competition, and 3) public discourse.

How specifically did the regression of democracy manifest itself and in what way did it create more favourable conditions for the rise of right-wing extremists and the consolidation of their positions?

Exercise of power and performance of institutions

ĽSNS was elected to parliament twice – in 2016 and 2020. In both cases, this happened after the end of an election cycle in which the national populists ruled or dominated in the governments. The parliamentary elections in 2016, when the ĽSNS was elected to parliament for the first time, had key importance for the establishment of the right-wing extremist movement as a relevant political force. This happened after the 2012–2016 election cycle was completed, in which Smer-SD ruled independently, as the only ruling party, without coalition partners. In the 2012 early elections, Smer-SD won 44% of the vote and gained an absolute majority in the parliament.

The conditions for such unprecedented electoral gain for Slovakia and the subsequent high concentration of power emerged for Smer-SD as a result of the election failure of the centre-right democratic parties. This failure happened due to their inability to secure governance throughout the whole cycle after the victorious 2010 elections. In autumn 2011, the ruling coalition SDKÚ-DS – SaS – KDH – Most-Híd, after less than 1,5 years of its operation (July 2010 – October 2011) lost confidence in parliament as a result of intra-coalition conflict over one policy issue (it happened during the voting on Slovakia’s endorsement of the EFSF). This interrupted the hopeful process of improving the quality of democracy and, on the contrary, freed up the space for national populists to act in the opposite direction and, as it turned out later, created favourable conditions for the rise of right-wing extremism.

In 2012–2016, Smer-SD, as a single ruling party, tried to gain full control over influential state positions in a way unusual for a liberal democracy. In doing so, it not only violated the norms of procedural consensus, but even proceeded in contradiction with the law. The Smer-SD held all important state positions including prime minister, speaker of the Parliament, president (until 2014), chairman of the Constitutional Court, chairman of the Supreme Court (until 2014), prosecutor general, head of the secret service, heads of all regulatory and control authorities. The degree of concentration of power by one political party – the ruling Smer-SD – has been unprecedented in the context of developments since 1989.

By consolidating power, Smer-SD marginalized the opposition in the parliament, prevented the participation of its representatives in the implementation of parliamentary control, ignored and blocked the legislative initiatives of opposition MPs. Violation of the basic principles of the procedural consensus has been subsequently openly trivialized by Smer-SD. For political reasons, Smer-SD attacked the plenipotentiary for human rights (ombudswoman), who pointed out the number of legal misconducts towards citizens caused by the state institutions; it demonstratively ignored the ombudswoman’s office findings, thus questioning the seriousness of the human rights agenda.

Smer-SD practiced open clientelism and nepotism in personnel nominations to public posts and in distribution of funds from public sources (especially in the implementation of the state’s large economic projects, in public procurement). As a result of selective justice, no criminal liability was practically inferred against the leading members and loyalists of the ruling party or persons who maintained clientelistic ties with this party if they violated the law.

The real depth and extent of the illiberal regression of democracy was highlighted by the events that took place in the country in 2018–2020. An investigation into the assassination of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová, an investigative journalist and his fiancé, revealed the links between the activities of criminal actors in the business environment and representatives of the highest constitutional institutions (government, parliament, Constitutional Court, Supreme Court, individual ministries), police, prosecutors and courts. Although the intention of those involved was primarily to obtain unjustified personal benefits on a corrupt basis, the nature of these ties and the intensity of their practical operation began to take on a systemic form. Only the massive protests of citizens in March–June 2018 and the subsequent political changes including the replacement of the government after elections in February 2020, contributed to disrupting these shadow ties in the publicly known cases.

The weakening of Slovakia’s democratic institutions, a direct result of activities of the national populist forces, not only worsened the quality of democracy but also set a precedent. It gave an example that such practices are feasible despite the declarations of respect to the norms of democracy. It can be perceived as a model that could be used by political forces with a more radical profile and a more openly anti-democratic program to realize their intentions. It was not only the reality that was important, but also its perception by people. The power practices of the ruling Smer-SD caused a critical decline in the credibility of the institutions of constitutional system (government, parliament, courts). In public opinion polls, the share of those who did no longer trust the mentioned institutions significantly exceeded the share of those who trusted them. Among large number of voters the dissatisfaction with the exercise of power, especially with corrupt practices and dysfunction of institutes of the rule of law, has led many citizens to be dissatisfied with democracy as a system. In the minds of people, democracy has been associated with distortions, corruption, and injustice.[7]

This atmosphere undoubtedly played in favour of ĽSNS. The party’s representatives linked the narrative of the corrupt, “anti-national” and “anti-people’s” political elite, both governmental and opposition, with the narrative of the current democratic system as a political “theatre” with the pre-agreed political actions. They also spread the narrative of the whole post-1989 transformation period as an irreparable failure and lost opportunities. They presented their party as a new political force, untouched by corruption, and at the same time a victim of unfair treatment, against who the whole corrupt system united. ĽSNS proposed to solve the social problems “sharply” by going outside the democratic system, using repressive methods, applying restrictive and protectionist measures, discriminating against entire sections of the population, imposing self-isolation of the country, and severing ties with the EU and NATO.

After its election to the parliament in 2016, the ĽSNS significantly expanded its modus operandi. The status of the parliamentary party not only removed obstacles to its political legitimacy, but also provided a platform for much more intensive communication with the electorate, using funds from the state budget and enjoying broader access to the media. It continued to spread its toxic illiberal narratives, including the narrative of an inefficient and corrupt democratic system. The moods of the public, marked by general dissatisfaction with corruption and the conviction of many citizens about the corrupt nature of the existing political system, created a favourable environment for ĽSNS’ activities in this direction. According to the CSES and ISSP Slovakia 2016 survey conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences and the TNS Slovakia agency, a high level of the public’s persuasion about corruption of the country’s political system persisted and the share of such people even increased. While in 2008 55.8% of respondents answered that many or almost all politicians are involved in corruption, in 2016 58.7% of respondents thought so, and voters of ĽSNS considered politicians corrupt in higher degree than the sample.[8]

At the background of the high level of citizens’ belief that system is corrupt, the level of tolerance for radical ideas has grown. The same survey showed that there has been a fundamental shift among the population in tolerance of the activities of people with radical views, such as the intention to overthrow the government by revolution. A comparison of the responses in the 2008 survey with the responses in 2016 showed that while in 2008 only 38.2% of respondents would ‘certainly’ or ‘rather’ allow such people to organize a public rally, eight years later, 60.8% of respondents would do so. The analysis showed that the tolerance of activities of people with radical views was strongly related to the belief that many politicians are involved in corruption. As many as 75.4% of those respondents who answered in 2016 that almost all politicians are involved in corruption would ‘certainly’ or ‘rather’ allow radicals to hold public rallies (compared to the mentioned 60.8% in the whole sample).[9]

For its pre-election mobilizing activities the ĽSNS used an unsuccessful attempt of the Supreme Court to dissolve it in April 2019. The party used the court’s decision as a recurring argument to justify its legitimacy, claiming to be a standard democratic party, not a fascist entity, although the judgment of the Supreme Court did not contain anything like that (it only stated that the petition for ĽSNS’ dissolution submitted to the court by prosecutor general did not contain sufficiently convincing evidence).

The case of the unsuccessful attempt to dissolve the ĽSNS was a clear example of the failure of the institutional mechanisms aimed at protection of democracy against the actors who threaten it. The fact that the prosecutor general was unable to prepare a quality filing (or to supplement it within almost two years of the whole proceeding) when there was sufficient amount of incriminating evidences in publicly available sources of information or that the Supreme Court found no evidence at all in the 21 pages of the prosecutor general’s filing for dissolution of the extremist entity, testified to the lax approach of the institutions which had in their competence the protection of the state’s democratic character.

Serious doubts about the verdict of the Supreme Court were raised even more by the publicized parts of the communication of the mafia entrepreneur and mobster Marián Kočner, sentenced to a long prison term for financial machinations and charged in the case of the assassination of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová. Kočner revealed to his confident who was also involved in his criminal activities that in 2018 he, Kočner, allegedly “arranged” (pre-ordered) in the Supreme Court that the ĽSNS would not be dissolved, mentioning the name of a female judge who would have to decide about this case, and indeed later, in April 2019, she really was a member of the court senate which refused to dissolve the extremist party.

Party politics and electoral competition

Political competition between national populists and programmatic parties has been focused exclusively on seeking power. The fact that a constituent part of the political spectrum is an extremist formation, which poses a threat to democracy, is not fully taken into account in such a competition. This was the case in the period 2012–2016, when the ĽSNS operated as a non-parliamentary force with weak electoral support during almost the entire election cycle, but in the elections it eventually succeeded to enter the parliament. Although the political relevance of the ĽSNS has increased significantly, there has been no major change in the approaches of the main actors to party competition. The importance these actors attach to maintaining power at any cost is far greater than the importance they place on maintaining democracy as a system. This is most evident among national populist forces.

In 2016–2020, relations between the ruling coalition led by Smer-SD and the centre-right democratic opposition were marked by sharp confrontation, and the ĽSNS stayed out of this conflict. Smer-SD attacked the democratic part of the opposition in particular, as it perceived it as the main challenger, as a force that could oust it from power and subsequently would focus on criminalizing and penalizing its leading figures. Smer-SD accused the centre-right opposition of repealing the government’s social measures and impoverishing workers if they would win the elections. A discourse arose that Smer-SD did not want to relinquish power in favour of the opposition due to its fears about the opposition’s anti-social setting, on the other hand the opposition argued that it was necessary to replace Smer-SD because of its corruption. These were the main discourses of the 2020 election competition.

The debate that the ĽSNS poses a threat to democracy was secondary from the point of view of this overall electoral competition (absolutely invisible from Smer-SD’s side). This discourse was developed mainly by non-partisan actors – by mainstream media, NGOs, public intellectuals. At the level of political parties it was present in the activities of selected individuals from the opposition parliamentary parties SaS and Spolu, non-parliamentary PS (party as a whole) and KDH (individuals); this discourse was to some extent also developed by individuals from the ruling party Most-Híd.

By analysing the process that led to rising right-wing extremism in Slovakia, it is evident that the election of ĽSNS’ leader Marián Kotleba as chairman (governor) of one of the self-governing regions – Banská Bystrica – in 2013 played a significant role.[10] This happened three years before the party got into national parliament. It was not a coincidence that the success of ĽSNS’ leader at the regional level contained the elements that later manifested itself at the national level – namely the connection between the rule of representatives of national populist forces with their approach to the execution of power in the previous election cycle and the election of the ĽSNS (or its representative) as well as a configuration of electoral competition (even with taking into account the specific electoral model applied in regional elections). Kotleba was elected governor after serving four years under Vladimír Maňka’s government, representative of Smer-SD, leading representative (vice-chairman) of Smer-SD, and member of the European Parliament.

So, in this case, the right-wing extremist became a relevant actor at the national level after the previous cycle of national populist’s rule.

The configuration of party competition also played a role. Because the competition in the elections of governor in Banská Bystrica region took place between the national populists and the centre-right democrats, the probability that a right-wing extremist would eventually win the elections was considered extremely low. However, such considerations proved to be far removed from reality. The confrontational nature between the national populists and the centre-right democrats made agreement impossible between these two camps about the joint support of Smer-SD’s candidate against Kotleba in the second round. As a result, ĽSNS’ leader eventually won with a significant lead – 55.53% of the votes in the second round, while in the in the first round he has got only 21.30%.

When the ruling coalition was formed in 2016 in an unusual alliance of national populist (Smer-SD and SNS) and programmatic parties (Most-Híd and Sieť),[11] the leaders of all these parties justified their unlikely coalition as a testament to fighting against right-wing extremism and fascism (that is, against ĽSNS, which was elected to parliament for the first time, shocking voters). However, this promise was not fulfilled, activities in this direction were not effective, and the individual parties acted on their commitment to fight extremism in an uneven way.

Leading representatives of Smer-SD avoided the issue of combating extremism in their public speeches (with the exception of commemorative events dedicated to the Slovak National Uprising of 1944, in which, indeed, the historical context was dominant, not the current country’s development). Anti-fascist rhetoric was used from time to time by the chairman of the SNS and speaker of parliament Andrej Danko, who criticized ĽSNS’ leader, but this was more Danko’s individual activity than the internalized position of the whole party. Danko’s statements did not find much support inside SNS. His primary intention was to weaken the right-wing extremists electorally in favour of his own party, in other words to take away part of ĽSNS’ voters for the SNS. Eventually, the SNS failed and lost the elections in 2020. The only ruling party that took some practical steps to curb extremism was centre-right Most-Híd, which had the Ministry of Justice in its executive portfolio,[12] but individual activities of the party’s representatives could not substitute the lack of systematic and comprehensive work against extremism pursued by the entire coalition.

ĽSNS’s isolation and ostracization from the rest of parliament, introduced at the beginning of the election cycle, did not last the entire tenure. Indeed, legislative proposals submitted by ĽSNS’ deputies were supported by deputies of the opposition “We Are the Family” movement. At the end of the election cycle, when Smer-SD needed to approve the laws that – as the party was convinced – could increase its support in the election campaign, Smer-SD tried to obtain endorsement for its proposals among the ĽSNS’ deputies, and when laws were approved with support of ĽSNS’ MPs, Smer-SD’s leader Robert Fico openly expressed his gratitude to them.

Public discourse

Party politics and public discourse during this time were plagued with anti-liberal and anti-democratic xenophobia. After 2015, this was a trend directly linked to attempts to lower the credibility of the EU as a community of liberal democracies and to call into question the liberal democracy as a system. It manifested itself inter alia along two thematic lines – in the migration/refugee issue and in the so-called cultural-ethical agenda (gender, LGBTQ, reproductive behaviour, family model; in the aggregated form it was present in the so-called Istanbul Convention agenda). In both mentioned lines, ĽSNS was very active, and in the 2016 and 2020 elections it used them to mobilize and consolidate its electoral base.

In the immediate period before the 2016 parliamentary elections (second half of 2015 to beginning of 2016), an intolerant atmosphere was formed in Slovakia in connection with the refugee crisis in Europe. ĽSNS representatives were assertive in feeding the anti-refugee hysteria, but they were not the strongest actors in doing so. It was the ruling Smer-SD, which used the personnel, administrative, and material resources available for it as the only government party. The way in which Smer-SD handled the refugee issue, especially its illiberal anti-European rhetoric, legitimised from the voters’ point of view even the most radical attitudes and proposals that were constituent parts of the overall anti-immigrant discourse. This was undoubtedly an advantage for right-wing extremists: part of the voters saw the ĽSNS as a more sincere, open and, most importantly, authentic fighter against the “threat” of immigration.

During the refugee crisis, the ĽSNS intensively propagated an anti-European narrative, which sought to tear down the liberal and multicultural EU by removing the basic social, cultural, and civilizational characteristics of Europe. According to ĽSNS, Europe was shaped by “white” conservative and Christian values and should remain that way. Smer-SD helped the ĽSNS in promoting this attitude by widely publicizing statements made by their leader, Fico, about the supposed cultural incompatibility of Islam and Muslim refugees with the European way of life.

In 2019–2020, the ĽSNS actively opposed the ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (the Istanbul Convention) by parliament. The party’s representatives spread disinformation about the document’s contents and its consequences. They fear mongered about hostile “liberal forces” from Europe trying to destroy the organic Slovak way of life and undermining the traditional Slovak family. Similar rhetoric was used by national populists either (especially by SNS, but also some individual representatives of the Smer-SD as well as by conservative elements in the centre-right spectrum). It was the national populists who shortly before the parliamentary elections initiated deliberations in the parliament about rejecting the Istanbul Convention. This, in turn, created a suitable space for the ĽSNS to spread its defamatory content against the “liberal” EU.

Tellingly, the two ruling parties – Smer-SD and SNS – and the extremist ĽSNS converged on how they interpreted the assassination of Kuciak and Kušnírová, which was of great importance for the country’s further political development, from several perspectives. Indeed, there was an important discursive aspect that was directly related to the relationship between the regression of democracy and the rise of extremism in Slovakia. This was the way the assassinations were interpreted by the two ruling parties and the extremists. The national populists (Smer-SD and SNS) and extremists (ĽSNS) believed that the case of Kuciak’s and Kušnírová’s assassination and its circumstances was a conspiracy and an intervention by hostile external forces (West, USA, George Soros). They claimed that hostile agents carried out the assassination in order to disrupt Slovakia’s political and national development, and to promote their own interests that were alien to Slovakia. These two political camps appeared to unite over this issue, and their common interpretation of the crucial event became another opportunity for extremists to assert their legitimacy and gain public support.

Conclusion

The strengthening of right-wing extremism as an ideological and political movement in Slovakia is one of the most significant trends in the country’s socio-political development in recent years. Certainly, it is remarkable that this took place thirty years after the fall of the communism and after a fairly successful democratic transition and integration into the EU. The establishment of a fascist party as a relevant political force in Slovakia poses a real threat to the country’s democratic achievements, as well as to the protection of human rights and to the long-term sustainability of liberal democracy not only in Slovakia, but in Europe more broadly. However, as this paper demonstrated, the deterioration of democracy in Slovakia did not begin with the ĽSNS’ arrival to the parliament. Instead, right-wing extremists exploited the democratic deficits created by the national populist’s authoritarian and corrupt practices that preceded them.

Countries that experience a democratic backslide create favourable conditions for the rise of extremism. That said, weakening democratic institutions as a result of corruption and authoritarian policies can be strengthened through peaceful public pressure and in full compliance with the constitutional framework of a liberal democracy. In other words, through civic engagement, it is possible to prevent a society’s destabilization and exploitation by extremists. In this respect, it is now up to the democratic parties that came to power after the parliamentary elections in February 2020 to strengthen Slovakia’s democratic institutions, which were weakened after many years of populist and authoritarian leaning government. Indeed, it is their responsibility, as elected democratic parties, along with the support of active citizens, to restore democracy and to create stronger guarantees against the possible resurgence of right-wing extremists that threaten the country’s future as a liberal democracy.

List of parties’ acronyms and names

ANO (Aliancia nového občana) – Alliance of New Citizen

HZDS (Hnutie za demokratické Slovensko) – Movement for a Democratic Slovakia

HzOS (Hnutie za oslobodenie Slovenska) – Movement for Liberation of Slovakia

KDH (Kresťanskodemokratické hnutie) – Christian Democratic Movement

ĽSNS (Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko) – People’s Party Our Slovakia

Most-Híd – Bridge

NaS - ns (Národ a spravodlivosť - naša strana) – Nation and Justice - Our Party

OĽaNO (Obyčajní ľudia a nezávislé osobnosti) – Ordinary People and Independent Personalities

O-VNPK (Odvaha - Veľká národná proruská koalícia) – Courage - Great National Pro-Russian Coalition

PD (Priama demokracia) – Direct Democracy

PSN (Práca slovenského národa) – Work of Slovak Nation

PSNS (Práva Slovenská národná strana) – Real Slovak National Party

SaS (Sloboda a solidarita) – Freedom and Solidarity

SDK (Slovenská demokratická koalícia) – Slovak Democratic Coalition

SDKÚ (Slovenska demokratická a kresťanská únia) – Slovak Democratic and Christian Union

SDKÚ-DS (Slovenska demokratická a kresťanská únia - Demokratická strana) – Slovak Democratic and Christian Union - Democratic Party

SDĽ (Strana demokratickej ľavice) – Party of the Democratic Left

SHO (Slovenské hnutie obrody) – Slovak Revival Movement

Sieť – Network

SL (Slovenská liga) – Slovak League

SĽS (Slovenská ľudová strana) – Slovak People’s Party

Sme rodina – We Are the Family

Smer-SD (Smer – sociálna demokracia) – Direction - Social Democracy

SMK (Strana maďarskej koalície) – Party of Hungarian Coalition

SNJ (Slovenská národná jednota) – Slovak National Unity

SNS (Slovenská národná strana) – Slovak National Party

SOP (Strana občianskeho porozumenia) – Party of Civic Understanding

SP (Slovenská pospolitosť) – Slovak Togetherness

SP-NS (Slovenská pospolitosť - Národná strana) – Slovak Togetherness - National Party

SS-SNZ (Strana slobody – Strana národného zjednotenia) – Freedom Party - Party of National Unification

Vlasť – Motherland

Za ľudí – For People

ZRS (Združenie robotníkov Slovenska) – Workers’ Association of Slovakia

[1] Szomolányi, Soňa – Gyárfášová, Oľga – Orth, Martín: Národná elita: od polarizácie ku konsenzu in: Szomolányi, Soňa (ed.): Spoločnosť a politika na Slovensku. Cesty k stabilite 1989–2004. Univerzita Komenského, Bratislava 2005, pp. 199–246.

[2] Mesežnikov, Grigorij – Gyárfášová, Oľga: Slovakia’s Conflicting Camps in: Journal of Democracy, July 2018, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 78–90.

[3] Mikušovič, Dušan: Mimoparlamentná krajná pravica. Masarykova univerzita v Brně, Brno 2006; Kluknavská, Alena: Krajné pravicové strany v parlamentných voľbách 2012 na Slovensku in: Rexter, No. 1, 2012.

[4] Mikušovič, Dušan: Slovenská pospolitosť včera a dnes in: Rexter, No. 1, 2007.

[5] Budajová, Michaela: Programatika a ideológia Ľudovej strany Naše Slovensko a Slovenskej pospolitosti – národnej strany in: Politologická revue, No. 1, 2018, pp. 89–121.

[6] Goliaš, Peter – Hajko, Jozef – Piško, Michal: Populism and corruption are main threats to democracy in Slovakia. Country report on the state and development of democracy in Slovakia: A failure to address problems and abuse of power opens the door to extremism. INEKO, Bratislava 2017.

[7] In this context, it can be recalled that in the first period of his tenure as a leader of the opposition party, Robert Fico spread the narrative that democratization after 1989 created in Slovakia favourable conditions for corruption. It was the narrative through which Smer’s leader criticized the liberal economic reforms, saying that pluralistic system increased the level of corruption in the country (See more: Mesežnikov, Grigorij: Protikorupčná agenda v činnosti vybraných slovenských politikov (1998–2008. Bratislava 2010 – at:

http://www.ivo.sk/buxus/docs//rozne/Mesez_TIS_korupcia_final.pdf).

[8] Názory občanov na korupciu a ich osobná skúsenosť: Politici a úradníci sú stále skorumpovaní. Osobná skúsenosť s korupciou je však zriedkavejšia ako pred ôsmimi rokmi. Tlačová konferencia v rámci projektu APVV-14-0527, 3.2.2017, SAV at: http://sociologia.sav.sk/cms/uploaded/2543_attach_Bahna_Zagrapan_korupcia.pdf

[9] Tolerancia radikálnych názorov narástla a súvisí s vnímaním skorumpovanosti politikov. Tlačová konferencia v rámci projektu APVV-14-0527, 3.2.2017, SAV at: http://sociologia.sav.sk/cms/uploaded/2543_attach_Bahna_Zagrapan_radikali.pdf

[10] Kluknavská, Alena – Smolík, Josef: We hate them all? Issue adaptation of extreme right parties in Slovakia 1993 – 2016 in: Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 49 (2016), p. 338; Gyárfášová, Oľga: Slovakia: Radicalization of radical right. Nativist movement and parties in the political process in: Caiani, Manuela – Císař, Ondřej (eds): Radical Right Movement Parties in Europe. Routledge, Abingdon/New York 2019, p. 210.

[11] From 1990 to 2016, the ruling coalitions operated in Slovakia consisted either exclusively of national-populist parties or exclusively of programmatic parties; no coalitions were formed with the participation of parties of both types at the same time.

[12] The Ministry of Justice submitted several legislative proposals restricting the activities of extremists (for example, an amendment to prevent their attempts to replace police authorities in “protection of the population“ by the so-called “train patrols” that groups of ĽSNS’s members began practicing in Eastern Slovakia to intimidate local Roma). Despite the approval of the amendment, the members of the ĽSNS continued to demonstrate their physical presence in the trains.

The article gives the views of the author, not the position of the "Europe’s Futures–Ideas for Action" project or the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM).